Feature: Reviews

Invisible Dynamics

Every day we interpret our habitat through pictures: photographs, drawings, and films, maps and signs, plans and diagrams, We are so comfortable with this visual language of place that we take it for granted, until we encounter a different dialect in an unfamiliar culture and must grapple with new conventions. Each element in this visual vocabulary of location — every landscape painting, film location and architectural facade, every subway map, circuit diagram, and real estate window display — is an invention honed by use. It transmits information that has been of interest in the past; as new needs and interests arise, new images follow.

In my capacity as co-coordinator of the Center for Art + Science at the San Francisco Art Institute, I worked in various ways with artists Peter Richards and Susan Schwartzenberg of the Exploratorium as they developed Invisible Dynamics, an ongoing research project. Invisible Dynamics applies contemporary spatial information technologies to creating new images of the San Francisco Bay region. It’s an unusual, long-term project; for the first stage a suite of commissioned art works was created that may, in turn, become starting points for projects by other artists and scientists. Four of these projects occupied a bay of the South Hall exhibition at ISEA 2006 in San Jose. Crossing the domains of art, design, geography, cartography, sociology, hydrology, marine science, and history, Invisible Dynamics might be simply described as generating multi-dimensional landscapes. Except that the limited scope of the word “landscape,” with its connotations of framing and venerating certain kinds of places, makes it a paltry descriptor for the generous, open boundaries and active engagement that characterize the works of Invisible Dynamics.

19th century landscape painters brushed an alluring image of California as green, open country; in their works the people who already lived here were, for the most part, invisible. The land appeared to be empty, free for the taking; thus the paintings of Albert Bierstadt, William Keith, and others invited settlers. Immigration is still a central issue for the Bay Area, but contemporary artists such as Ricardo Rivera foreground the social negotiations of migration — who can come, who can stay, whose presence is noted and whose is erased. For Rivera’s Invisible Dynamics project, “Move Here,” he collected film clips promoting the region to prospective Californians. He then used anamorphic projection to create symbolic viewing conditions: the viewer must change his or her position to locate the “sweet spot” where the liquid flows of imagery resolve into recognizable come-ons. The turbulence of the imagery becomes a formal analog for changing conditions of immigration: as human populations mix with increasing turbulence, the “invisible dynamics” governing their motion are pressing concerns.

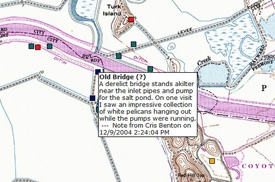

The “green country” of the painters was idealized, but it was not imaginary — the Bay region was and is a fiesta of natural life. While it might seem that the green country has succumbed to the settlers, shaved, paved, and deadened, its forces still permeate the city and its environs. The forms of the watershed pattern urban neighborhoods, and streams still gurgle beneath concrete. In the wake of human activity, such “invisible dynamics” are re-forming the salt flats of the South Bay, one of the post-urban spaces investigated by the “Hidden Ecologies” team comprised of architect Chris Benton, microbiologist Wayne Lanier, and artist Marina McDougal. With equipment ranging from kite-flown cameras to field microscopes and GPS mapping systems, the trio has recorded invisible or barely-visible aspects of the site such as microbial communities, evidence of long-decayed buildings, and forgotten cultural histories. Through a Web-based annotation system, this information accretes on master maps.

Basic natural rhythms, such as night and day, also appear in the real-time mapping of taxi rides created by artist Scott Snibbe with Stamen Design. The “invisible dynamics” that can be discerned in this beautiful deluge of data include social and economic forces as well. Like a weather reporter’s satellite map, “Cabspotting” translates millions of bits of information into a picture human brains can process. Thousands of times a day, a yellow cab pulls to the curb, a door slams, a ride commences. “Cabspotting” composes each vehicle into a general image of circulation.

“Trace,” by artist Ali Sant and programmer Ryan Shaw, is another map-in-motion, chronicling the “on” and “off” zones of the wireless network. This map does not easily resolve into a pattern — the fluctuating tracks of the taxis are stable compared to the wireless zones, which blink in and out of existence in response to desires — “invisible dynamics” — that are more individual and less predictable than, say, the desire of many passengers to go to the airport in the morning.

This exhibition was a progress report; like the phenomena they reveal, the works in Invisible Dynamics are in motion. When Invisible Dynamics next appears in public the works here will be transformed by time and perhaps by other investigators. “Cabspotting” has already been adapted for a new project by artist Amy Balkin.

As the various images generated by Invisible Dynamics filter into the visual language of place they will travel through many channels, not just the channel called “art.” Early paintings of California landscape partook of their time and technology; they were rooted in the same world view that led to studying butterflies by pinning them in a collectors’ case. The technology of our time enables images of place that vary, accumulate, and transform; this is of a piece with a world view that emphasizes context, data, and dialog — our own, networked perspective.