Feature: Reviews

Raindrops on Roses

- Mission 17, Adobe Books, and [ 2nd floor projects ]

- Mission District, San Francisco

Simple Pleasures when Scared Shitless

Blabbable Doodads, Miriam Dym & Eunjung Hwang, Mission 17

How to Slow Down, Kyle Ranson, Adobe Books

AHA, Sahar Khoury, [ 2nd floor projects ]

First in a series of reviews of alternative venues in the Mission District.

How does one find meaning in the chaotic, apocalyptic world surrounding the humble, insignificant individual? Three recent San Francisco exhibitions ask this eternally relevant question. Through the use of media and imagery that at first glance appear child-like or naive, they contradict the simplistic expectations of the viewer and point to complicated resolutions.

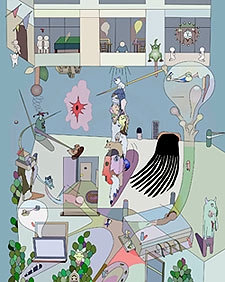

Blabbable Doodads, which just closed at the non-profit gallery Mission 17, provides an anarchic view of the present and the future. I find Eunjung Hwang’s work, culled from her “Fabulous Creature” series, disturbing and fascinating. Her animations and digital prints initially conjure 1970s children’s cartoons, filled with psychedelic imagery and pastel-colored, flat line drawings. However, Hwang contradicts the viewer’s expectations by filling her expansive worlds with troubling details, creating her own version of a disturbed Richard Scarry Busytown book.

The inhabitants of Hwang’s works are both infantile and robotic. Faceless humans dressed in diapers or sporting tadpoles embrace, worship, and murder in a sprawling environment cohabited by fanged monsters, toilets, assembly lines, and bodily orifices: a pink clouded asshole floats above the bustling city life. Hwang’s architecture consists of irrational buildings and distorted architecture, reflecting the constructs of an over-stimulated mind. There is no cohesive structure or focus to her universe, only a vast, sprawling plane interrupted by pockets of activity. By paying equal attention to the mundane and the horrifying, Hwang provides an oddly objective perspective of the world.

But what is Hwang’s ultimate suggestion, or conclusion? There is no clear didactic path to redemption. I believe that this is a positive aspect of Hwang’s work - I dislike art that beats you over the head with a clear-cut and unambiguous moral. I prefer the Socratic Method: works that gradually cause you to challenge your own beliefs, as opposed to artwork that preaches. In one digital print, a solitary female sits on the edge of the world, her back to the viewer. She turns her back on the chaos, facing an unknown, blue abyss. In another print, a line of bicyclists also turn away from the viewer, escaping over hills into a mystery. Perhaps Hwang is suggesting that redemption lies in the unforeseeable future. Perhaps ‘nature’, or what is left of it, provides some kind of relief from the hyperactive world.

In contrast to Hwang’s futuristic dystopia, Kyle Ranson’s works depict a biblical idealism. His exhibition at Adobe Books offers a view of men and women equally united with each other and the wilderness surrounding them. His rich, bright paintings are compulsively filled with marks and brushstrokes. Although Ranson’s work seems very different from Hwang’s, they share many commonalities. Both suggest meditation and escape from chaotic city life. How to Slow Down is an apt title of the exhibition, which may refer both to the physical act of meditating on each brushstroke that fills a canvas as well as a look backward to what many believe was a simpler time.

The very new space Second Floor, essentially the sun-drenched living room and hallway of artist and curator Margaret Tedesco, provides an intimate refuge from the anonymity both of city life and traditional art galleries. Her space is an ideal location for artwork: it simultaneously isolates the viewer from the messiness of every-day life while providing the space to examine and interpret it at a distance. By providing a welcoming and unpretentious atmosphere, the viewer can let down her guard and self-consciousness to become truly immersed in the artwork. While it may be a faux pas to discuss the space in addition to the artwork, I find it very difficult to separate the experience of the viewing environment from the actual work. Luckily, the artwork on view is strong in its own right.

AHA, the inaugural exhibition of [ 2nd floor projects ], features the sculptures, paintings, and prints of Sahar Khoury. Like Kyle Ranson, her work appears deceptively simple. Khoury uses mainly humble materials: paper mache, twine, newsprint, broken glasses. She works with the stuff of children’s crafts to create engaging facsimiles of every-day objects, evoking the work of both Eva Hesse and Claes Oldenburg. Khoury’s work draws both upon the fantastical and the anthropomorphic. Instead of depicting a macrocosm, Khoury draws insight and meaning by focusing on the ordinary. She links rough-hewn telephones and hula hoops to the more fantastical: e.g. geometric, gem-like paintings and a whimsical sculpture of a bear with a knife. At the same time, these collected moments and reflections point to greater epiphanies. One large sculpture, leaning against a corner, forms the symbol of infinity.

These three exhibitions all face the timeless: while everything eventually crumbles and wastes away, paper disintegrates, and the oceans begin to subsume the land, people nevertheless look toward art to achieve something either more substantial or transcendent. Eunjung Hwang analyzes the morbid efficiency of the world while looking at its literal fringes for an escape: some hills and empty space. Kyle Ranson seeks to slow down the harried pace of contemporary existence. Sahar Khoury focuses on the microcosmic as the foundations for both meditation and dreaming. All three artists search for the things that resist the pettiness and decay of everyday life; the hope of pleasure, fantasy, and meaning. Although these artworks do not provide a consistent solution, they still suggest a potential beauty and redemption.