Feature: Reviews

Jon Rubin

- Lizabeth Oliveria Gallery, Market Street Art in Transit

- Oakland, San Francisco

The solo projects of favorite bands-be they offshoots, or the product of a split—are always received with a mixture of hope and anxiety. You never know whether the members are just as good, if not better on their own, or whether the group efforts were so successful because of chemistry- a whole greater than the sum of its parts. Like ,um, Stevie Nicks (who currently has a solo album ready to drop.) On her own you get a sense of who she is, and what she contributed to the band that made her famous.

You could extend this equation to include artistic collaborators who have gone their own ways. When I began to see exhibitions and projects by Jon Rubin, the more reserved half of the clever, Bay Area-based collaborative team Fletcher and Rubin, (a partnership that resulted in some trenchant and humorous portraits of various people and communities) I wasn’t quite sure what to expect. Happily, it turns out that Rubin’s solo work more than holds its own, reflecting as well as moving beyond the successful aspects of his collaborative endeavors.

The first to appear were Rubin’s elegant series of Market Street Art-In-Transit kiosk posters that depict enlarged, isolated images of plants that have managed to survive city pedestrian traffic and sprout up on the paved sidewalks of Market Street. The single bits of foliage are shot against a white backdrop, with an address printed below, presumably where the picture was taken. You can almost imagine the artist carting around his seamless backdrop and camera equipment, as if on a plant identification mission. The images are elegant, like plant diagrams of weeds that grow in San Francisco. But like Fletcher and Rubin’s best projects, the process oriented pictures focus our attention back on the evolved order of nature and culture as it plays out in actual public space. At the same time, he lends these lowly shrubs a sense of dignity.

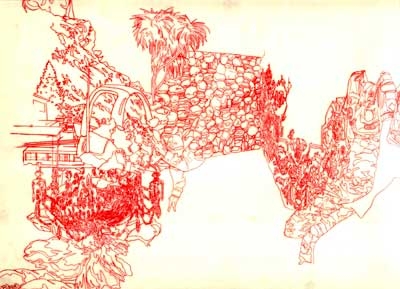

Notions of private space, that inside the home, become much more outlandish in Rubin’s impressive recent works on paper and video at Lizabeth Oliveria Gallery in Oakland. The core of this show was a series of intricate red pencil drawings on vellum, most titled “Forever.” They’re curious compositions of 1970s vintage furniture, wall treatments, hedges and shag carpets that seem to have been grafted together through an exquisitely rendered game of exquisite corpse. The end results seem like gravity defying, somewhat anthropomorphic interior decorating schemes that still manage to look fabulous.

Though almost all of these pictures are devoid of human presence (and in that attribute share something with the perfect architectural utopias painted by Kevin Appel), a strong sense of the personal manages to seep into Rubin’s drawings. One of the works in the series points directly to autobiographical origins: “Forever, Lower Merion, Class of ‘81” is made up only of faces-dozens of them overlaid one atop another. The picture seems like a ghostly cartoon chorus, a peer group nightmare carefully traced from the artist’s high school yearbook. The pictures tap into the kind of campy suburban ennui explored in films such as Ang Lee’s “Ice Storm” and Sophia Coppola’s “Virgin Suicides.” The drawings allude to narratives of twisted childhood memories of the family abode, as well as schoolyard taunts. The fact that these images are traced adds an intriguing conceptual layer. The interior magazine and the yearbook function as templates from which to live by and to encapsulate personal history. They’re barometers of style that may be mass distributed, but as lived-in rooms and experiences, they become something more.

Another series, depicting furnished rooms from the pages of vintage Architectural Digest magazines, are far more painterly endeavors. These show decorator composed rooms that each include a painting by a famous artists, for whom each are titled: “Kawara,” “Neel,” “Guston,” and “Picasso.” They literally seem to be dream homes, as Rubin renders them as dazzling constructions of busy wallpaper and bed spread patterns visually tied to the architectural spaces with wispy watercolor washes that fill in as floors and walls. In each of these rooms, the famous painting hanging on the wall is lovingly rendered in a realistic manner that contrasts with the more impressionistically-drawn décor that surrounds it. These seem less charged than the “Forever” works, yet are visually more complex and impressive. These do seem to be utopian spaces that any art conscious person would be happy to luxuriate in, for a good long time.

Jon Rubin

March 6-3, 2001 at Lizabeth Oliveria Gallery, 942 Clay Street, Oakland, CA 94607