Feature: Reviews

Alex Webb: Crossings

- Museum of Contemporary Art

- San Diego

- September 21 - December 7, 2003

Closed(minded) View of Migrants

Alex Webb’s photographic exhibit of Mexican-American border images recently closed at the downtown location of the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego. It was a true profile in the sense of being a partial view and a curiously myopic testimony to the endurance of stereotyped imagery.

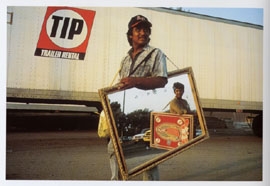

Webb’s photographs portray towns on both sides of the political boundary between Mexico and the United States, and emphasize the maquiladora-runoff homogeneity that defines, and defies, this line. The pictures fit somewhere between record and forgery. They demonstrate what mainstream media tells us to be true about the personality of the borderlands. Although the show includes portraits, Webb uses people somewhat like props in a theatre of predetermined impact.

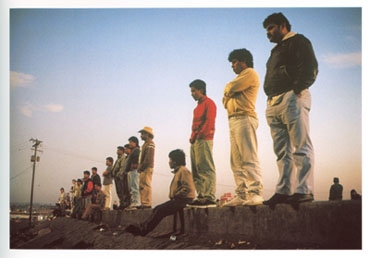

Though it is the central emblematic, semi-permeable backdrop for his fantasies of arrival, ascent, disappearance, descent, faith, and rebirth, Webb only sparingly photographs the border itself. In Tijuana, B.C., 1995, Webb shows us a row of men standing still, staring in unison into the horizon. With the border fence left out of in frame, the men become their own kind of wall, and this is the barrier Webb promotes most purposefully and successfully. In describing psychological homelessness, he cuts his subjects off from of any intended destinations. The concept of destination is discarded, and the significance of searching is valued alone. The salvation associated with the United States, El Norte, is relieved of its inevitable anticlimax, and the anticipation of its discovery is preserved.

Webb worked as a photojournalist, not an artist, for most of his career, and his talent for illustrating print headlines shows its bald knees here. He strips his subjects down to one or two interchangeable personalities. Their lives are made crisply romantic in their Kerouacian restlessness and idle poverty. The romance of hardship is Webb’s source of glamour, and the show’s static solemnity is very glamorous indeed.

The appeal of Crossings is not, then, in its faithfulness to human experience, but in the exhibit’s tendency to behave as an allegory. The predictable choices Webb makes with his pictures are a method for convincing the viewer to see symbolic structures instead of literal ones. In reducing culture down to its most naive face, he pushes the viewer away from anthropological curiosity. He steers us, by accident, into seeing the model of all things that imagine transformation through escape. Whether this spirit legitimately belongs to the people in Webb’s photographs becomes an almost illegitimate question. They are train cars empty of their secrets so that they may contain our own.

Homelessness is literally insisted upon through photographs of migrants sleeping outside buildings and on desert floors, but also through the overt absence of any pictures set within the home. There is not a single shot of a domestic interior. All the images were made in the street, in a place of business, or in the rough. It is as if people in the border towns do not have homes, temporary or otherwise, to return to.

If we question whether these people are true participants in the search that Webb depicts, or merely inhabitants of it, we are not answered clearly. Nueva Loredo, Tamaulipas, 1978 shows a single woman leaning against a pole at the curb outside the nightclub she presumably works in, reading a book under the neon light. In studying her repose, we understand her waiting as an essential element of the psychology of searching. But we also cannot be completely convinced that she is not simply inert.

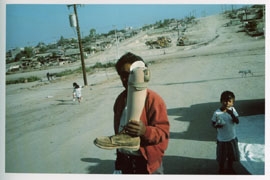

The works in Crossings are very careful not to judge the question of failure vs. success. In Colonia Matamoros, Tijuana, B.C., 1995, a man holds up half of a prosthetic leg, covering his face. It is impossible to be sure if it belongs to him or someone else because we do not see below his waist. A barren neighborhood stretches behind him. The false limb, dislocated and unable to fulfill wishes for mobility, is the tender ghost of this exhibit.

The Mexican-American border is a place of transfusion, dispersion, and exit. It is a place, both literally and figuratively, dependent on its own unknowable nature, just as Webb’s use of the subject is dependent on his own inability to understand it. His sentimental attachment to his limited vision makes for photographs that are sympathetic without being empathetic, logical without being explanatory. The fable that develops in the place of the document he had intended is a useful one. But though at times his work is very moving, the serious content of Webb’s photographic essay on migration is, regrettably, just travel size.