Feature: Conversations

An Interview with Deborah Oropallo

Deborah Oropallo’s February exhibit at the Wirtz Gallery was called Replica, but it was not a reprise of the type of picture making we have seen from Oropallo before. Neither was it a complete sea change, but her curiosity about all things quotidian seemed more pointed. Moving on from photographs of the industrial miscellany that surrounds her Berkeley studio, Oropallo is making mixed media prints that focus on children’s toys and the implications of manufactured play.

The works are marked by a gregarious, conventional design sense which makes for a clear bifurcation between visual devise and conceptual armature. Her concepts do not have absolute authority over her image construction. The visuals, which collage photographs of toys with painted and digital manipulations, have some amount of autonomous ideology, and stick in place with a seductive sense of zero gravity. The compositions have a magnetic fixation with the center of the image space. The palette is brighter and sweeter than her previous works, and has almost a print ad sensibility. What Oropallo has adopted is a kind of pop melody approach, a lullaby aesthetic.

“I wanted to make them beautiful,” says Oropallo. “And I think my work to some degree has always had that, a certain desire for beauty. It’s been criticized in a lot of my work. But in some ways it’s just what comes out of me unconsciously, like handwriting.”

Oropallo simulates the architecture of childhood, be it her own, her children’s, or an abstract general model, but the central consciousness of the work is undeniably parental. In her work, childhood playthings are partially cast, partially excavated, as demonstrable proof of developmental conditioning. This verdict, true or not, is one of adult hindsight. This is hindsight that Oropallo courts, sometimes just as a way of discrediting it.

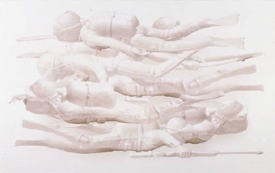

“I think I saw a lot of these objects as things that kids desire that make adults nervous,” she said, as we walked in front of Arms, the piece she thinks best unifies the themes of the exhibit. “For example, when your kids want to pretend war and want to play with guns, you question them doing those things. But I played war in the fifties. It’s just something that kids do. There is a complication of what you want for your kids, what you want in the world, what the kids think they want, and what they actually desire.

“After September 11 there was this proliferation in the G.I. Joe aisle. It went from a small stand of action figures to a massive surplus of all things military. For Arms, I started with a vacu-form container that had held all of the little toy guns inside the G.I. Joe packaging. In my finished image you can still see traces of the illustration from the toy package, which was a scene of orange trees and these soldiers coming out of a helicopter or something. I ripped it off and put my own more bucolic scene behind it, of a little boy from a 17th century tapestry pushing a girl on a swing. I took out the plastic guns, and filled those vacu-form hollows with sugar.”

Perhaps the scraps of behavior suggested by childhood toys are unambiguous yellow bricks in the Freudian road of future neurosis. Through our early emotional attachments to objects we learn to locate surrogate fulfillment, and in the postindustrial world, these objects of our affection are simultaneously both personal items and commonplace junk. The selection of things that make us happy is arbitrary and circumstantial, and even more strangely, it is mostly an experience we share with a vast percentage of our specific generation.

“In terms of the simple object,“Oropallo said, “typically it’s just those things around me. I think what I look for is material or an object that means something more than what it is. Something that contains echoes. Mainly my work is a reflection of the circumstances in my life, and I have two kids, a boy and a girl. I make observations about the toys they have, and about the way they play. I look at those objects and see adult themes. They’re doing adult play. Everything is in miniature, and in this work I’m blowing it back up to adult size. That’s why the show is called ‘Replica.’”

There is an inevitable way in which parents superimpose their own childhood over the surface of their children. The title “Replica” is also suggestive of this process, that childhood is something that is replicated. Oropallo’s toys are actors, and her work is an exercise in reproducing a collective memory. Generationally, the objects themselves may change, but the life cycle of this type of middle-class childhood is recovered through the perpetuated possession of such things.

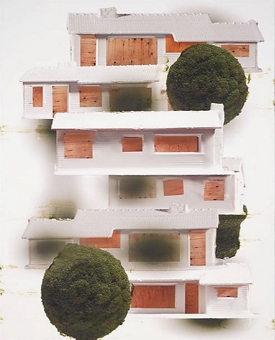

“For the piece Free House, I began with one of those little suburban ranch houses from a model train set that I bought. They came in different colors, all with the same floor plan. One of the reasons I was attracted to those houses was because of the New Jersey neighborhood that I grew up in. My grandfather had built our house. He was a bricklayer. We had this big, four-story brick house that was covered in ivy, with Spanish arches, and to me it always seemed sort of haunted. It was like the Edward Scissorhands house. There was a porch where my mother always said the lions should go, and as a kid I never knew what that meant. In the meantime they were busy developing this other area of the street, building these small suburban houses. The whole American dream of the fifties was to have those little houses, and I desperately wanted that, too.”

Free House belongs to a trio of works which also includes Vacant, and Door to Door. All three pieces feature antiseptically dilapidated suburban houses free floating in an opaque vacuum, two of them with hallucinogenic spots of craft store shrubbery, green tracers included. The houses appear to have never been occupied, boarded over simply as another step of their construction. They are the object of wishes never fulfilled, the shells of fantasy, and the windows are covered because the interiors do not even exist.

“I was assembling the toy houses, and when I got them all together I didn’t like the way the colors looked, so I decided to paint them. In Berkeley they have all these old houses everywhere that they don’t know what to do with. They couldn’t give them away if they wanted because no one would take them. So they put plywood on them and paint them white to make them more invisible. That’s what I decided to do with my houses. I also dipped them in wax to eliminate much of the plastic detail. I’m always trying to soften the definition, and dissolve the images a little more.”

Frequently, she uses wax as a finish on her canvases. This, in conjunction with soft focus photography, can make her images appear to rest a fraction of an inch below the actual surface of the picture plane. They are returning, or leaving, or simply in motion. They are communicating the phantom density of governed memory. We must consider that all of these various objects could, in fact, be removed from her pictures altogether, or be replaced by other very different things. Through childhood, as the child becomes individuated, isn’t the physical environment little more than a collection of props that surround development, rather than an indication of it? Objects can facilitate longing, or be a facsimile of it, but they are never responsible for it.

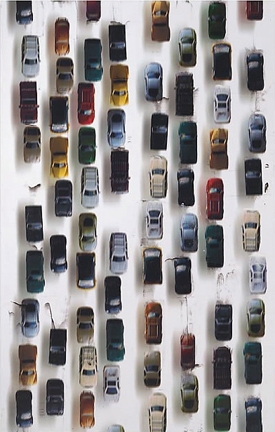

The toy car, for example, is representative somehow of the urge for maturation, but does not at all own that anxiety. To telescope metaphor from something is different than to understand that object in terms of any given abstraction. Oropallo does not pretend to, and instead she asks us: where does the importance of such an object actually reside, especially when its definition changes, but the psychic existence of childhood continues separately?

“Have you ever wondered how, as an adult, these things can come to mean the complete opposite? The desire to drive when you’re young means a lot of things, like escape. But as an adult I had a period where I was so claustrophobic that I couldn’t even cross the bridge without medication. It wasn’t a freedom at all. That car for me had become this acquired inability to escape.”

In her piece Drive, the crowd of Life-Saver colored sedans teeters between appearing like a gathering at a drive-in movie and looking like a traffic clot on the CA-101. The image is also not a stage at all, but a method of expressing the imaginative dimensions of fixation. The multiplication of an object has been a longstanding pillar of Oropallo’s technique, and with it we see the blunt variation on the theme “replication.” She repeats the same item many times within one piece, even repeating the same picture of the same item, not unlike pop art sequencing. This deliberate visual stutter is a way of delivering the multiplicity of memory, the innumerable interactions with a single object, and its recurrent actions. Like Warhol’s method of serializing, it is a way of admitting the collective memory consecrated by consumer products.

“I often use repetition as a way of relating to the mass production of industry. You can obviously read other things into it, but for me it is almost literal in that sense. It is not just a visual idea. It’s more directed towards the idea of repetition as it occurs in things that are already multiples.”

By multiplying these objects she is assisting them in gaining language and abstraction, but there is also something funny going on here.

“I’ve always had humor in my work, even though not everyone has seen it that way. There is only one friend who would always come to my studio and comment on the laughter in the work. I think it’s important in art to be uplifting. Even though the things in this show can have a darker side, they can also function purely as things from the toy store. That side of it is just about what is desirable, and what people like.”

Oropallo started her career working more traditionally with paint, but painting has become successively far less pivotal in her practices. Today it is more of an invited guest inside her work rather than something she could not produce without. In the “Replica” show, digital photography is the bottom line, and the visual editing she carries out could be done entirely on computer, rather than partially. She holds onto painting, but when looking at the work she has done over the last few years, the viewer is likely to wonder why she still paints at all.

“Working digitally gives you less control and more possibility at the same time, and that’s a challenging place to be when you’ve been painting for twenty years. I can’t find new things out in painting anymore. In terms of process, my work has always been photo-based. It’s always been more about printing than painting. But I still have this restless urge to make something and to still put my hands on it. I’m often still painting at every step, in one form or another. I’m painting all of these objects before I photograph them, and then I’m painting on top of the prints. That need for direct involvement is still there.”

Oropallo also said to me that art is often about “giving something up.” However, her artwork is mostly about the return of things. Memory itself is a recovery, and also an enactment, archival but not fossilized, because events and objects are always dressed in an evolving personal history. Being a parent, Oropallo sees the instruction of memory as a porous transmission, and a maternal one. I am reminded of the last lines of Claims for Lost Objects, by poet Maxine Chernoff:

Restored to you,

this backlit saga

Restored to you,

this alphabet of clouds.

I knew Debbie as a child. We had a lot of fun playing, singing, dancing and pretending on those front steps….she was incredibly talented back then and it’s been amazing to watch her creativity and inspirations continue to develop.

Lena Sheffield (Castaneira) • September 04, 2011