Feature: Conversations

Ben Wood - New Art from Ancient History

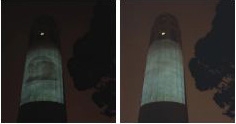

Editor’s Note: Ben Wood and David Mark will be presenting a digitally produced movie projected onto the south and west portions of Coit Tower commemorating the 100th anniversary of the 1906 Earthquake and Fire. The projection will commence the evening of April 17, 2006, and carry forth into the early hours of April 18th, coinciding with the moment the earthquake struck 100 years ago. This interview was conducted before the event’s schedule was known.

The British artist Ben Wood is gracious about answering questions, but it’s clear his mind is elsewhere—specifically, underneath the façade of the Officer’s Club in San Francisco’s Presidio. He’s on his way there to document the excavation of an adobe wall which is one of the two oldest structures in the city. This is how he’ll be spending the next month, and he’s not yet sure how he’ll make use of the digital images he’s planning to take: Perhaps a video collage projected onto the side of the current building? Such are the conundrums that come with making new media art out of ancient history. Wood has to remain open not only to future possibilities—fresh ideas, advances in digital imaging, screening permits—but also to the possibilities that the past still holds, awaiting our (over)due consideration.

Alison Bing Your current Presidio project is a collaboration with the archaeologist Eric Blind, with whom you captured images of a 1791 Ohlone mural at Mission Dolores that had been covered by an altarpiece since 1796. How did that project come about?

Ben Wood I was thinking I wasn’t going to be in San Francisco much longer because my visa was running out, and I wanted to explore Native histories while I was still here. So I called up Mission Dolores one day, and to my surprise, they called me back. I went to visit Andy Galvan, the curator and a descendent of the Ohlone, to ask him what would be appropriate to show the Ohlone presence in Mission Dolores. He told me that behind the altar was an Ohlone mural, and the archaeologist Eric Blind had been trying to document it. So I called up Eric, and he was thrilled that somebody else wanted to do it. We have been able to photograph a big portion of the mural—maybe a quarter of it—and that hasn’t happened before.

The process was amazing, standing on top of the altar and lowering this camera down behind it with lots of pulleys, ropes and contraptions. Every now and then a camera flash would seep out through the cracks in the altar. It must have seemed very otherworldly from down below. I pieced together the photographs, and then projected a mural section depicting the sacred heart with a sword through it onto the dome of the church. The effect was quite ghostly. Senator Barbara Boxer used pictures of the mural to help support legislation for preservation of California missions, and I believe the measure passed.

AB You’re from the U.K., which has plenty of history of its’ own to explore. What brought you to California and got you so interested in our comparatively brief history?

BW I came here six years ago because I was interested in using the computer with my artwork and at art college in Brighton I was the only person doing that. So they brought me over to the digital program at West Valley College, and then I went to the San Francisco Art Institute to combine the technical knowledge I’d gained with a fine art education. I walked by Coit Tower every day, and there was a Columbus statue there that kept me thinking about the history of this place.

Within my process I talk to people all the time—most of the ideas I get aren’t mine, they’re from asking questions and investigating. I went down to Gilroy to talk to a Native lady and her family there, and she felt it would be nice if I conveyed Native history through older people, younger people, and objects. I met an Ohlone woman who works at San Francisco State, and recorded her making basketry and giving a blessing for graduating Native students. In Tiburon, I documented rock formations with carved patterns. Then I went down to Coyote Hills, the reconstructed Ohlone village in Fremont, and recorded grass blowing. I used the sky above as a blue screen, so I could show objects floating in mid-air and composite all this different information. The resulting film was shown as a projection onto Coit Tower.

AB What interests you in Native histories in particular, and how do you contend with the question of appropriation and ownership that incorporating Native imagery inevitably raises?

BW My family came to Britain as refugees from Germany, so they were not allowed to live in the place where they were born and maybe, subconsciously, that’s what prompted my interest in Native histories. I did a projection of the Ohlone mural at Mission Dolores at the London Jewish Museum of Art that made this connection tangible. But although I took the pictures of the Mission Dolores mural, I’m not allowed to give them to anybody else, since they’re not really mine to give. With the Coit Tower projection, they’re all documentary images I’ve taken. By compositing these images and projecting them onto a landmark, I’m raising questions, asking people to decide for themselves how they associate these different objects and histories.