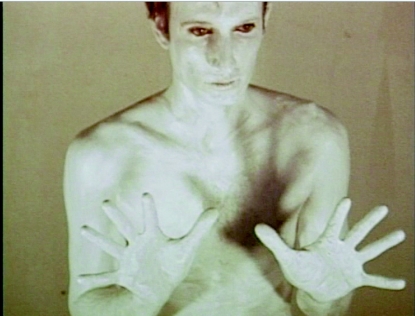

Art Make-Up No. 1, White (1967), 16 mm film, color, silent; 10 min.; University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive; museum purchase: bequest of Therese Bonney, Class of 1916, by exchange and BAM/PFA institutional support. Copyright 2006 Bruce Nauman/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

Art Make-Up No. 2, Pink (1967), 16 mm film, color, silent; 10 min.; University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive; museum purchase: bequest of Therese Bonney, Class of 1916, by exchange and BAM/PFA institutional support. Copyright 2006 Bruce Nauman/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

Art Make-Up No. 3, Green (1967), 16 mm film, color, silent; 10 min.; University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive; museum purchase: bequest of Therese Bonney, Class of 1916, by exchange and BAM/PFA institutional support. Copyright 2006 Bruce Nauman/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

Art Make-Up No. 4, Black (1967), 16 mm film, color, silent; 10 min.; University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive; museum purchase: bequest of Therese Bonney, Class of 1916, by exchange and BAM/PFA institutional support. Copyright 2006 Bruce Nauman/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

Feature: Reviews

Bruce Nauman: The Early Films and Videos

- Berkeley Art Museum

- Through April 15, 2007

In the midst of Northern California’s macho art culture,* at the height of the Vietnam War, catching the drift of early feminist performance art, Bruce Nauman went into the studio in 1967 and made Art Make-Up, a 16mm color film to be projected onto four walls of a small room It is projected onto four walls simultaneously so that, standing in the center of the room in the bright white light as though on a stage, the viewer is surrounded by images of the artist actor. The sound of four projectors whirs overhead. In this dense sensory environment, the viewer becomes an actor in the artist’s performance.

Art Make-Up is composed of four one-reel sections designed as a loop to play continuously. It is Nauman’s first film environment. In the film, he uses his body as a sculptural material.

In front of a stationary camera, Nauman repeatedly paints his face and naked torso, first white, then pink, green and finally black. He is an Abstract Expressionist painting, a bronze sculpture, a performance artist taking poses from heroic classical sculpture and then from female and drag fashion.

In his existential performance, the artist-actor reveals himself naked before the camera as he systematically “makes himself up,” covers himself and withdraws from public view. In Art Make-Up, Nauman creates an end-game circumstance to reveal the contradictory human needs for communication as well as for withdrawal and disguise. The film addresses the mutability of the self, and the construction of identity, race and gender.

Nauman’s Art Make-Up is one of 16 film, video and sound works in “A Rose Has No Teeth: Bruce Nauman in the 1960s,” organized by curator Constance M. Lewallen for the Berkeley Art Museum. The first in-depth survey of the artist’s groundbreaking works from 1964-69, when Nauman lived and worked in Northern California, the exhibition presents over 100 works, including sculpture, films, videos, sound and text work, installation, neon reliefs, photographs, drawings, artist books and ephemera.

“A Rose Has No Teeth” presents several significant pieces exhibited publicly for the first time, including four infrared outtakes and an untitled fiberglass and polyester resin sculpture from 1965. Lewallen discovered many of these works in Nauman’s friends’ studios in Northern California where they had been stored for 40 years.

Fitting together disparate media like a jigsaw puzzle, the exhibition lays out themes and subjects, objects and ideas of this early period. From this foundation, the more elaborated later works continue to flow.

Along with other artists of the period such as Andy Warhol and Michael Snow, Kenneth Anger and Ken Emshwiller, Nauman used 16mm film as an artist material. Nauman’s films are distinctive, however, in that they record his own studio performances in which he enacts and obsessively repeats everyday movements.

In 1967, he made Bouncing Two Balls between Floor and Ceiling with Changing Rhythms, a 10 minute black-and-white film with sound. The one-reel film plays continuously on a loop. The action takes place in Nauman’s studio; he is the sole actor costumed as an experimental dancer in black tee shirt and jeans.

The scene consists of studio clutter surrounding a square delineated on the studio floor. From the edges of this square, Nauman reaches in long arms to forcefully bounce first one, then another ball into the center, sometimes running after them Buster Keaton-like. (The film was made at the same time that he also filmed the performances, Bouncing My Balls and Painting My Balls Black.)

If Jackson Pollock’s action-painting in front of Hans Namuth’s camera was an enchanted improvisational dance in which the artist flung, spread and spilled paint, Nauman’s dance is a self-conscious and sometimes laughing one in which playful action engages accident to create a dance performance of physical exertion and endurance. The sound of bouncing balls is loud and polyrhythmic, experimental music composed by experimental dance.

If Nauman’s media are wide-ranging, so is his cultural context large. At the University of Wisconsin in the early 1960s, he studied philosophy, notably Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations — the title of the current exhibition is taken from a famous passage in Wittgenstein’s book — and studied mathematics and music. In math, philosophy and music, he was attracted to logical structure and its break-down. He has been quoted as saying that important artists explore the structure of their medium.

Also at the University of Wisconsin, Nauman saw and heard the work of John Cage and Merce Cunningham. In the Bay Area, he met and sometimes worked with the composer, vocalist and dancer Meredith Monk and Minimalist composer Steve Reich. He was aware of the experimental work with ordinary movement of the Bay Area choreographer/dancer Anna Halprin. He heard the music of La Monte Young and read the plays of Samuel Beckett and the novels of Alain Robbe-Grillet. He looked at the work of Man Ray and Jasper Johns.

At the University of California, Davis where Nauman received an MFA in 1966, he was close to and encouraged in his radical experiments by artist and teacher William Wiley, whose work is synonymous with the Bay Area’s take on the synchronicity of art and life and whose work has always been socially engaged. Wiley’s approach to art as an ethical practice supported Nauman’s already developed personal inclinations. Nauman was also supported by the generally off-the-wall, anything goes questioning of art’s function that then defined Davis’ art culture.

He exhibited his work with Nicholas Wilder in Los Angeles in 1966 and became aware of Andy Warhol’s work with everyday materials and with repetition and duration in film. Nauman’s 1966 film, Smoke, might be considered a loose, jocular Northern California take on Warhol’s more formalist film, Sleep.

In 1966, he was included by Lucy Lippard in the “Eccentric Abstraction” exhibition at Fischbach Gallery in New York along with Eva Hesse and Louise Bourgeois. In 1968, his work was included in the “AntiForm” show at John Gibson Gallery, New York with Richard Serra, Eva Hesse, Keith Sonnier and Richard Tuttle and ” Nine” at the Leo Castelli Gallery, organized by Robert Morris. That same year, he has his first one-person show at Castelli.

In the 1968 black-and-white videotape, Bouncing in the Corner I, Nauman placed the camera in a horizontal position so that the artist-actor appears horizontal, dressed in black and white, on screen. Seen from his feet to the lower part of his face, Nauman slams his shoulders back into the wall and then back out toward the camera. This is an arduous, repeated movement, especially when done for 60 minutes as it is here. It is painful to observe.

The sound in Bouncing in the Corner I, is the thudding of Nauman’s body against the wall which sounds like a bellows breathing air under pressure. Hans Hofmann had been a key teacher at the University of California in Berkeley. Is this strenuous performance a riposte to Hofmann’s teaching of push-pull color dynamics in painting?

If, as Nauman has said, the most important decision an artist makes is what to do, then this videotape is about the artist activating the videotape’s grey field with the painful physical activity of his own body. It is also about how we commonly get ourselves into and out of tight corners and how much pressure the space of corners can exert on our sense of ourselves.

In Stamping in the Studio, another videotape from 1968, Nauman films himself with an inverted camera placed high on the ceiling as he takes small steps, “stamping” back and forth across his studio floor. The reversal creates a studio-field in which the floor falls away and the upside-down artist marches against gravity.

The falling and rising sound of the artist’s marching feet is regimented, militarist, oppressive. Made at the height of the Vietnam War when young American men were faced with the military draft and heard tales of basic training at the many military bases in California, this videotape as well as Bouncing in the Corner I and the film, Art Make-Up are the artist’s urgent investigations into the conventions defining and circumscribing the male self.

Alongside these videotapes from 1968, the Berkeley Art Museum has installed several of Nauman’s Minimalist-appearing steel, lead and aluminum sculptures. Lighted Center Piece, 1967-68 is a floor-standing square piece of brushed aluminum with four halogen lights attached. Unlike Carl Andre’s aluminum sculptures as road, Nauman’s sculpture resembles the abstracted studio/stage/arena seen in his videotapes and films of 1967-68. The aluminum square is lit with stage lights and thus appears more related to a floor-standing Giacometti tableau than the Minimalist sculpture it at first appears to be.

In Untitled, lead, steel and water, 1968, Nauman creates a make-shift fountain, one where the water will rust the sculptural material from within. This low-lying form might well be the ultimate non-heroic sculpture and a send-up of Andre’s humble metal sculpture.

If Alberto Giacometti was the first sculptor to make sculptures as sites, Nauman moved the site from the city square into the studio. Wall-Floor Positions is a 60 minute videotape which originated in a public performance Nauman did at Davis in 1965 and videotaped in his studio in 1968.

In front of a wall, Nauman performs at least 28 movements in relationship to wall and floor, holding the positions for minutes. He stands on the floor with his back to the wall, then his face to the wall. He lies on the floor with his back to the wall, then his face to the wall. In each of these series, he positions his arms, legs and torso in different ways, sometimes in extension, sometimes rolled up in fetal position. From simple and easy to complex and pressured, from struggles to extend and balance his body to abject rolled up retreats, Nauman manipulates his long body to carve formal abstract shapes referencing abstract sculpture and painting and to carve abject shapes referencing Goya’s Disasters of War.

If one of the themes of Nauman’s work is how space and sound shape our awareness and our behavior, the arduous physical and imaginative exertions of Wall-Floor Positions dramatizes the imaginative resources we possess to respond to constricting circumstances.

* The 1960s “tough guy” aesthetic was centered at the University of California, Davis and at the San Francisco Art Institute. At UCD, the aesthetic was labelled “dude ranch dada” by the New York Times. At the San Francisco Art Institute, the aesthetic was a codification of Clyfford Still’s heroic rhetoric about painting and the artist life.

Embedded in this tough guy culture as Nauman was, his work very early on subverted it and was in sync with early feminist performance art. This non-heroic, and in fact abject attitude toward male experience and the male body, can be seen in his early performances, fiberglass and polyester resin sculpture and early films and videos. It is most fully realized in the 1967 film environment Art Make-Up. The influence of Nauman’s early sculpture, films and videos can perhaps be seen in the installations of Robert Gober and the sculpture of Kiki Smith.

“A Rose Has No Teeth” continues through April 15, 2007 at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, 2626 and 2575 Bancroft Way, Berkeley, CA 94720. After its appearance in Berkeley, “A Rose Has No Teeth,” travels to the Menil Collection in Houston and the Castello di Rivoli in Turin. The show is accompanied by a catalog with essays by Constance Lewallen, Robert R.Riley, Robert Storr and Anne M. Wagner.