Feature: Reviews

Cycle

- Future Primitive Sound Headquarters

- Through December 1, 2004

Cycle Wuz Here: A Vital Taste of the Old School

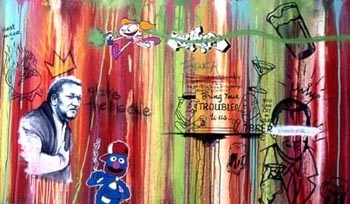

Crammed into a tiny studio in the basement of the Lower Haight’s Future Primitive Sound Headquarters—where paintings from graffiti stalwarts Doze Green and Budder aggressively clash for space— graffiti artist Cycle doesn’t act like one of the nation’s most lauded crossover artists. He’s soft-spoken and self-deprecating, with an introspective air that belies the dissonant playfulness of his work. But this might all be due to the fact that he’s hardly in his element.

"The nice thing about graffiti is that it’s very environmentally based," he tells me. "Right now, I’m sitting in this basement room doing art work. I could be sealed in here with no contact with anybody for as long as I want, but graffiti’s just the opposite… There’s some crazy homeless guy, a crackhead over there, a cop on the corner. You’re continuously coming into contact with stuff in your surroundings."

Cycle is more than just a parvenu of the art world, with its ineffable dichotomies and posturing of aesthetic legitimacy. Although he’s been a prime instigator of the current graffiti to gallery movement in cities like New York and San Francisco, it’s his public art—with its cacophony of cult images and urban hieroglyphics—that turns eyes and gets noticed.

Equipped with a style that he calls "loud and obnoxious," Cycle’s latest exhibit, entitled "Cycle Wuz Here," is a collection of paintings and one of a kind denim jackets that pays homage to old school graffiti imagery while demonstrating a conspicuous divergence from the traditional urban signifiers of graffiti and into a wider realm of cultural imagery. "Cycle Wuz Here," housed at the celebrated artist/record collective Future Primitive Sound, is the artist’s first show in San Francisco since 1999.

Cycle’s artistic emergence began when he was a teenager in New York City in the 1980s. In 1989, he moved to Washington DC to attend George Washington University. It was here that he would make his name and help transform the DC graffiti scene, which was generally characterized by gang markings and random vandalism.

"It was a fledgling scene at the time,” he attests. "There were a handful of us doing graffiti, but it was very scattered. It was not a homogenized scene. When the movement started to take root, it was an odd mixture of different stuff going on."

Cycle was responsible for introducing a cache of some of the more sophisticated styles and lettering that he’d picked up when he got his first taste of graffiti as a kid in New York City. His position at the forefront of the DC graffiti scene gave him a place in the 2001 retrospective Free Agents, an examination of the roots and evolution of DC urban art that garnered critical acclaim and enjoyed a corresponding exhibition at Washington DC’s Museum of Contemporary Art.

After obtaining his BFA in Fine Art, Cycle relocated to San Francisco, where he received a MFA in Illustration from the Academy of Art College. While in San Francisco, Cycle contributed a mural to Clarion Alley, the legendary fiat of the city’s public art, as well as a collaboration with the young students at Precita Eyes Mural Arts Center.

According to Cycle, the differences between west and east coast graffiti scenes reflect the cities’ ethos. “San Francisco has always had this artsy thing going on‚ “lots of images and characters aside from the old school lettering. But of course, New York is the Mecca of graffiti art.” Cycle cites the influential film Style Wars, produced by Tony Silver and Henry Chalfant, and directed by Tony Silver, in 1983, as a major influence. Henry Chalfant and Martha Cooper’s book Subway Art also triggered Cycle’s inspiration. “I love New York because it’s very old school and tradition-based. It has such an established and deeply rooted history,” he says.

A medley of nationally acclaimed exhibitions, boasting the likes of Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat (a.k.a. Samo) as well as later ingénues like Doze Green and Cycle himself, have cropped up in galleries across the world. According to Cycle, this resurgence of graffiti art as a legitimate artistic movement has happened before.

“In the 80s in New York City, graffiti was hot in the gallery world, and people like Crash, Daze, and Lady Pink began doing international shows in Japan and Europe,“says Cycle. “This is a second go-around for graffiti art, but it’s certainly enjoyed popularity in the past in the art world.”

Indeed, the emergence of graffiti as art was perhaps defined in the early 1980s, when Fred Braithwaite (a.k.a. Fab Five Freddy, and later, Freddy Love) was featured in the “Scenes” column of the Village Voice, in which he boldly stated, ” think it’s time everyone realized graffiti is the purest form of New York art. What else has evolved from the streets?” Following the article, Braithwaite received dozens of calls from international art dealers. In 1980, he also painted his own version of Andy Warhol’s “Campbell Soup Cans” on the side of a train, and went on to collaborate with pop music icons like Blondie. The effect of Braithwaite’s rise to the mainstream was concomitant with graffiti art’s influence outside a primarily urban space.

In the late 1980s, according to Cycle, graffiti art became more fragmented, and the gallery scene crashed. Shortly before this, graffiti art was being pulled in opposite directions; as art dealers were commissioning artists to reproduce their urban masterpieces on canvas, city government was spending millions to eradicate graffiti from the subway system. Artists were straddling the line between the art world and a deviant subculture.

Despite the evolution of urban art from its modest roots, Cycle questions whether or not graffiti nowadays is considered legitimate. “I almost could care less if it is,” he admits. “But hopefully, this time it sticks around and has some longevity.”

In 1999, Cycle moved back to New York City and became a designer for companies like Mecca, Think Skateboards, and Source Magazine. At the same time, his artwork made appearances in NYC galleries like SOMA and Bob’s Gallery, and appeared in countless magazines and retrospectives. Cycle also collaborated with a variety of notable urban art/nu-graffiti legends, including the Barnstormers, a legendary graffiti crew that stretched the boundaries of their work by traveling to rural North Carolina and painting on the walls of barns.

If graffiti is capable of surpassing the normal spatial boundaries of the urban space, it is perhaps the process of image repetition that is responsible for the rather recent phenomenon of graffiti as commodity—which is coupled with graffiti’s entrance into the mainstream and its appeal to youth culture marketing. “It makes sense. It’s the same principle as clothing companies that brand their work,” says Cycle as he shows me several paintings with the same motif: phosphorescent, spray-painted skulls surrounded by jagged bolts of chartreuse lightning. “In repeating one’s images, it’s like you’re creating a logo for your art. You’re branding yourself.”

If traditional graffiti is marked by monolithic lettering and characters, Cycle’s work is more like a collage, a mischievous confluence of pop art and traditional graffiti styles. He builds mixed media juxtapositions that place iconic images like a tongue-protruding Einstein alongside graffiti’s warped lettering. Unlike many graffiti artists who attempt the crossover to the gallery world, Cycle successfully integrates his urban, working class background with his fine art training. His paintings are compositionally sophisticated and at times thematically intricate, yet he is also able to incorporate a personal iconography—including signifiers like Rocky and Bullwinkle– that conveys a childhood spent walking the mean streets and absorbing Saturday morning cartoons. His individual images are immediate and undeniably masculine, yet there’s a certain critical distance in the composition, and the skulls and dragons are slyly subverted by a backdrop of pink and purple clouds.

Cycle will readily tell whoever asks that he is influenced by everything around him—friends, conversations with other artists, whatever is happening down the street. The proliferation of young artists who find inspiration in his work and the work of other predecessors is also heartening to him, and has him convinced that the graffiti movement is much more far-reaching than art snobs might tell you it is.

“Graffiti has increased, even with law enforcement against it, and people constantly cleaning it, and political campaigns against it,” says Cycle. “When I started paying attention to graffiti, it was a localized thing in New York subways. Now, there’s cities in the Midwest that have their own graffiti scene. If it’s continually growing like that, there’s got to be some validity.”

Future Primitive Sound Headquarters is located at 597 Haight Street in San Francisco. For more information, call 415.551.2328.