Feature: Reviews

Doubletake: Gail Wight at SFAI

- Walter and McBean Galleries

- San Francisco Art Institute

- August 29 - October 11, 2003

Take One: Matthew Carver/Take Two: Olaniyan Adams

The Evolution of Disarticulation

Take One

by Matthew Carver

I stopped in at the SFAI gallery one Friday when I had a couple hours to kill. No one was at the reception desk. I looked at the various papers on the desk; there were some announcements and invitations for different shows. A stack for Wight’s show. A stubby pencil and a ball-point pen. A cup of coffee, no longer steaming. I stood there for a second, thinking about where the gallery attendant might have gotten to, because I had some preliminary questions to ask before turning right — and suddenly! the posters! These were great posters, huge digital prints hung from cord like scrolls. I was awestruck.

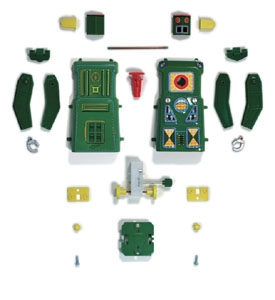

The images of dismantled toys held me for a good hour. Displayed in an almost honorific way, the peltified mechanical beings were laid out symmetrically on white backgrounds (presumably by some mad scientist, maniacally grasping at straws for new species) and photographed under light from some sort of intense examining lamp. Each part cast thick, distracting shadows on the airy space beneath. “Computer-generated shadows?” They were the sort of painted metal toys you think could not have been made very recently or sold very locally. They must have come from some dark corner of a shop in 1970’s Hong Kong.

These were not everyday symbols. Despite their maniacal arrangement they had the sorts of associations with “olden days” inherent in the metal toys that wound up and walked or rolled with clumsy gruesome motions, and sometimes spat out sparks from their eyes or mouths. Of course none of these could still roll or spit — no dragon here. Here were cleanly dissected forms, forms which every child should be familiar with, or perhaps would have been thirty or forty years ago. Our commonest and friendliest animalia images. Dissected — splendid! We could have no guilty feelings with these scientific investigations. They were dismembered metal — dead — but it was okay, since they were never living to begin with. This got me to thinking about the little bugs pinned in neat little boxes, and the bones bolted together in places like the Smithsonian, and the heads on game hunters’ walls. In contrast, this was a menagerie for modern times, sterile, guiltless and simple. Here the categories were clear and distinct (the gaudily painted details on the exaggerated bodies told us for sure what they were: mouse, cat, elephant).

How did these works fit with the title of the exhibition? Were these evolutions, were they disarticulations, or both? Definitely the latter. Dissections are disarticulations. The toys were literally disarticulated, that is, their joints were separated, their members separated, they were wholly disconnected in themselves. But couldn’t there be a deeper sense in which they were disconnected? Couldn’t they be disconnected from us? And couldn’t they perhaps show us how disarticulated our notions of the animals are: from ourselves as conscious humans, and from our synthetic schema which ought to fit everything and make everything so clear and simple and easy to name — clear and simple like the inkjets hanging on the walls, clear and simple and distinct and distant like these crude reifications of symbols of animals, cut up, photographed, scanned, computerized, digitalized, Photoshopped, printed out and hung up in little boxes (rectangles) on the walls of a big box (gallery)?

How many children had been taught by similar devices to emulate the biological diagrams, to copy them into their brains, to make the pathways that put the tiger over there and the monkey over here? The monkey is brown and has a curly tail. The tiger is orange and has black stripes. The disarticulations were multiplying at a dizzying rate, faster than bunny rabbits. These objects, which I might have found cool or “keen” or “peachy” in a kitschy Polynesian-themed collectibles shop next to the plastic bins of little robots — they took on many different layers of meaning in Gail Wight’s smart rearrangement and recontextualization.

Take Two

by Olaniyan Adams

with epigraph by William Blake

The Tiger

TIGER, tiger, burning bright

In the forests of the night,

What immortal hand or eye

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

In what distant deeps or skies

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand dare seize the fire?

And what shoulder and what art

Could twist the sinews of thy heart?

And when thy heart began to beat,

What dread hand and what dread feet?

What the hammer? what the chain?

In what furnace was thy brain?

What the anvil? What dread grasp

Dare its deadly terrors clasp?

When the stars threw down their spears,

And water’d heaven with their tears,

Did He smile His work to see?

Did He who made the lamb make thee?

Tiger, tiger, burning bright

In the forests of the night,

What immortal hand or eye

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?

— William Blake

Relative to the work of Gail Wight, the idea of “that which is terrible” as evinced by the poet Blake becomes a double entendre. Wight’s often formally symmetrical dissections of robotic toys are terrible both in the way Dostoevsky used the term — really beautiful — and also in the sense in which Kierkegaard used it, to refer to banal tautologies that don’t withstand close inspection.

In this exhibition the artist combines these much-too-perfect symmetries with a series of flawed comparisons. Double becomings revolve around relationships between far-flung states of being, where wind-up toys are exchanged for real animals, which in turn become somewhat human, alive with the requisite elements (emotion and intellect, to name a few.) Like her colleague Catherine Chalmers (who shares wall space with Wight and others in the Berkeley Art Museum exhibition Genesis), Wight lapses into a cute but dangerous anthropomorphism, bringing together, even at times substituting for each other the aforementioned very different states of being. These states are really incomparable (except possibly upon the level of the most superficial resemblance — e.g. a video of a field mouse interacting with its robotic counterpart.)

It is clearly apparent in today’s reality that no machine comes close to accomplishing the feats of nature evinced by even the meekest of beasts (running, giving birth, breathing for years). Yes, dogs really can do simple arithmetic, whales sing well, bugs build stratified societies and chimps dance when they want it rain. However, other creatures cannot write Italian sonnets, come up theories of relativity, build cosmologies, dance like Michael Jackson or walk on the moon, Armstrong-style. Mice don’t just fashion themselves into (wo)men. The anthropomorphic metaphor is a common one, easily identifiable on the level of culture. What we must retain is the ability to distinguish cultural / communal movements (bears, Twinkies, gym rats, et cetera) from the enterprises of creative individuals.

The artist states her interest in making Foucaldian poetry, making distinctions by taking objects that have never lived apart, to form anatomies. This is exactly what she does. However, most learned poets avoid the inefficient and unwieldy use of six-syllable words. Unfortunately the artist bears a cathexis to a piece of clumsy medical jargon that seems out of place in our sound-byte driven world. Bringing all that she seeks to accomplish under the hole-filled umbrella of this one drawn-out and overreaching term does her work a real disservice. Instead it clouds what is an otherwise substantial array of concepts that deserve the distinctions she claims to want to give them. This funneling of all her ideas into an unstable mass christened ‘“disarticulation” distracts from her likable ambitions.

If beautiful robots still can’t feel anything, this work is not poetry but a science fiction, a Utopia, a moralistic fantasy of a world without nerves, where the foundations of the scientific inquiries she mimics simply don’t exist. A building without a foundation, such as hers, has a difficult time standing.