Feature: Reviews

Eva Hesse

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

- February 2- May 19, 2002

It is something, it is nothing:The “non-work” of Eva Hesse

I would like the work to be non-work. This means that it would find its way beyond my preconceptions…It is the unknown quantity from which and where I want to go. As a thing, an object, it accedes to its non-logical self. It is something, it is nothing.

— From Hesse’s statement for her 1968 exhibition Eva Hesse: Chain Polymers at the Fischbach Gallery, New York, quoted in Lucy R. Lippard, Eva Hesse (New York; New York University Press, 1976), p. 131

Possibly the best introduction to Eva Hesse is no introduction at all. I first saw her work around fifteen years ago at the Museum of Contemporary Art in L.A in a large group exhibition of American Minimalist artists of the 1960s and ‘70s. You had your Judds, your Andres, your Irwins, and your Flavins: an impressive display of industrially fabricated, meticulously machined, formally pristine, rigorously systematic, coldly elegant, aggressively untouchable (why bother?), muy macho objets d’art. I turned a corner and suddenly there was something unexpected to look at. Two somethings, actually: a wall piece and a floor piece, both wonderfully eccentric. My first reaction was to gasp, then laugh out loud. A laugh can be a complex response; incredulity, delight, recognition of a kindred spirit, were components of that one.

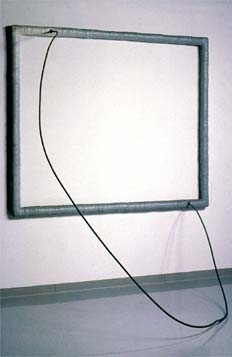

The wall piece (Hang Up, 1966) is a large, empty, rectangular picture frame, laboriously hand-wrapped in painted cloth, from which protrudes a lascivious, tongue-like loop (steel tubing wrapped in cord, then painted), that lolls down to the floor and literally extends itself to you, the viewer, daring you to interact with it. It’s awkward, ungainly, almost grotesque, yet compelling - endearing, even. The image it creates is absurd, vulgar, funny, and expressive, like a rebellious line describing a body part which has escaped from the picture plane, declaring independence from Flatland and the frame’s imprisoning geometry. It wants to be embodied, sexual, three-dimensional. DON’T FENCE ME IN. Like Hang Up, the floor piece, Repetition Nineteen III, (1968), acknowledged and challenged the premises and tactics of all the other work in that exhibition. It’s a seemingly random grouping of eighteen (originally nineteen; one hasn’t survived) translucent, columnar vessels made of fiberglass and polyester resin, tall enough to be phallic, open enough to be vaginal. They’re similar to each other but each one is individually molded, with its own idiosyncratic tilts, indentations, and imperfections, reflecting the characteristics of the material and the hand of the maker.

The aesthetic sense is almost Japanese, although the way these fragile golden vessels hold and transmit light shares affinities with mystical traditions in Western image-making. I had never seen anything like this piece, which then appeared to me extraordinarily beautiful. It still does. The objects themselves, and their improvisational arrangement, describe the ambiguity and contingency of the way things are in this world. The vessels look rigid yet malleable, substantial yet ephemeral, absurd yet dignified, stalwart yet vulnerable, obviously related yet individuated and stubbornly unique. They’re abstract yet have the bearing of personages. The piece borrows the notions of seriality and the systematic organization of the grid - fundamental Minimalist principles - only to disrupt them. (Nineteen is a prime number, impossible to grid.) Both works were like externalizations of Minimalism’s Jungian shadow: audacious metaphors for the return of the repressed, created with a keen sense of humor and even keener mind, hand, eye, and heart.

Eva Hesse died in 1970 of a brain tumor, aged 34. Her exhibiting career spanned ten years, from 1961-1970. Her production during that brief decade was prodigious - in quantity, in the increasingly radical originality of her practice, and in the accelerating urgency and visionary daring of her artistic evolution. Hang Up and Repetition Nineteen III were included, along with hundreds of other works, in the comprehensive Eva Hesse retrospective co-organized by Elizabeth Sussman and Renate Petzinger for the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. In the thirty years since her death, Hesse has survived her co-option as a feminist martyr (the Sylvia Plath of visual art) to become recognized as one of the most important and profoundly influential artists in the second half of the 20th Century.

If you missed the show at SFMOMA you’re out of luck, unless you can get to the Wiesbaden Museum in Germany, where it opens in June, or to Tate Modern, London, its final venue in 2003. The Whitney Museum in New York cancelled it due to post 9/11 budget constraints. Although this was the second Hesse retrospective in a decade - a 1992 exhibition organized for Yale University Art Gallery traveled to the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C. - there may never be another on this scale. Thanks to Hesse’s commitment to fugitive materials like latex, fiberglass, and polyester resin (she felt art works, like organisms, should be subject to decay, respond to the pull of gravity, and have a finite life span) many of the more fragile works in the show may not survive another trip. Several of her pieces have disintegrated already.

This exhibition traces Hesse’s entire artistic journey, from her paintings of the late 1950s (she began, surprisingly enough, as a painter), through her works on paper (watercolors, gouaches, collages, drawings with pen, pencil, and colored inks) and relief paintings, to the sculptures and sculptural installations she made until the year of her death. The reliefs are literally ‘reliefs’ in that you can tell by looking at them how liberating it was for her to propel those zany hybrid biomorphic/machine forms she’d been drawing right out, in full color, into three-dimensional space. When I saw Eighter from Decatur (1965), a wacky pink, yellow and white whirligig contraption (tempera paint, cord, and metal on Masonite), jump off the wall in a gallery otherwise hung with convoluted if exquisite line drawings, I thought ‘You go, girl!”’ Top Spot, (1965), is another gem. It uses industrial detritus (enamel paint, metal conduit, cord, plastic pipes, metal hardware and bolt, and wood on particle board painted a pretty aqua perfect for the suburban bathroom) to riff on the Minimalists’ use of industrial materials as examples of faulty plumbing and wiring. After this, there was no stopping her.

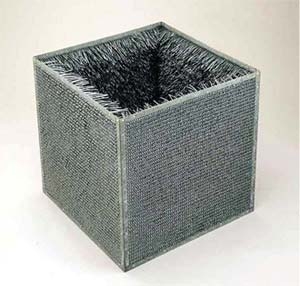

The last half of the show is devoted to the work for which she is best known: the ‘eccentric abstractions’; the gridded and quasi-Minimalist pieces like Accession I, II and III, (1968) (perforated topless cubes whose interiors bristle with loops of vinyl tubing - Donald Judd meets Meret Oppenheim); the late drawings (grids of obscured ‘windows’ - Hesse’s mother killed herself by jumping from a window); and the late sculptures exploring the properties of materials like latex, fiberglass, polyester resin, rope, cloth, vinyl tubing, metal mesh, polyethylene sheeting, and pigment. Hesse was voracious and eclectic in her influences. At various stages in her practice you can see how she absorbed and transmogrified the work of Josef Albers (her teacher at Yale, whom she loathed), de Kooning, Klee, Gorky, Roberto Matta, Kandinsky, Guston, LeWitt, Bourgeois, Bontecou, Judd, Andre, and Jackson Pollock. Her last piece, Untitled, (1970) - a tangled, knotted ceiling hanging of latex over rope and string - is clearly a response to Pollock’s drip paintings: let’s make it airborne and see how it flies. It’s gloriously ugly, probably my favorite piece in the show.

Hesse’s influence on subsequent generations of artists is incalculable. But any artist practicing today who values process over product, or combines labor-intensive craft with rigorous conceptual content, or experiments with unorthodox and possibly toxic materials to make things as yet unseen, or goofs on Minimalism and other male-dominated aesthetic tropes, owes her a debt. As do we all.

Eva Hesse was on view at the San Francisco Museum of Modern art February 2- May 19, 2002. It will be at Museum Wiesbaden from June 11-13 October, 2002 and at the Tate Modern in 2003.