wa barik wa sallim alayhi kathiran kathiran kathira - Bestow upon him (The Prophet) Your blessings and peace, in abundance, in abundance, in abundance!

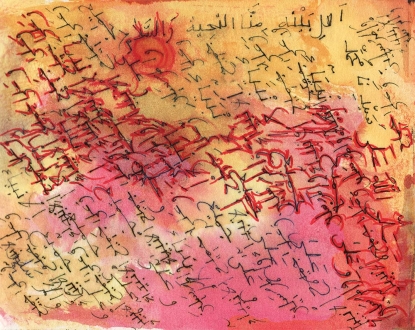

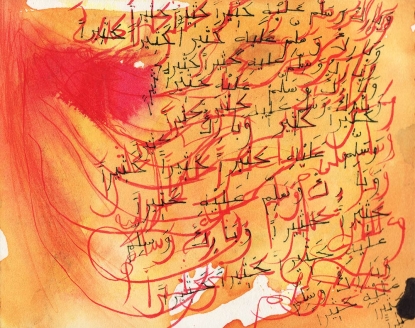

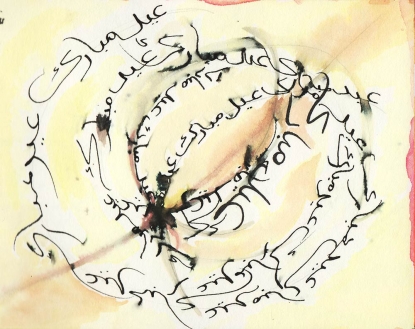

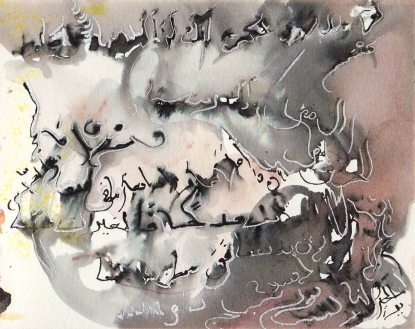

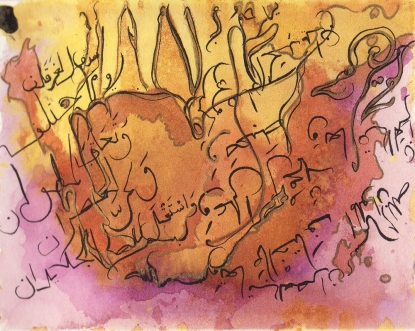

The Arabic text on the drawings is from a variety of sources such as The Qur’an, a prayer book, and from a traditional collection of words, phrases, and adjectives called The 99 Beautiful Names of God. The captions are an English transliteration of the Arabic.

Each image is 5” x 7” on watercolor paper, pen and ink, metallic markers, glitter; all were created between 2000-2003.

Click the images to see a larger view.

wa ala mala ‘ikatika wal muqarrabin - (May Allah bestow His peace and blessings upon our Master the Prophet) and on the angels and those close to the divine Throne.

wa ala jami ‘il anbiya‘i wal mursalin - (May Allah bestow His peace and blessings upon our Master the Prophet) and all the prophets and messengers.

Aminar-Rasul - The last two ayats (verses) from Surah Al-Baqarah in the Qur’an, praising the Prophet Muhammad.

wa baligh ruhahu wa arwaha ahli baytihi minnat tayyata was salam - Convey to his soul (The Prophet Muhammad) and the souls of the people of his house greetings and peace.

Eid Mubarak - A traditional greeting (meaning “Blessed Festival”) used during the festivals of the two major Islamic holidays: Eid ul-Adha and Eid ul-Fitr.

Eid Mubarak - A traditional greeting (meaning “Blessed Festival”) used during the festivals of the two major Islamic holidays: Eid ul-Adha and Eid ul-Fitr.

wa ala jami ‘il anbiya ‘il wal mursalin - (May Allah bestow His peace and blessings upon our Master the Prophet) and all the prophets and messengers

Feature: Essays

From Life-Art to Hijab

You may find yourself living in a shotgun shack.

You may find yourself living in another part of the world

You may ask yourself, well, how did I get here?

You may say to yourself, my God, what have I done?- Talking Heads, Once in a Lifetime

What happens when life is art?

Artists active in the Life-Art movement of the early 1970s influenced me, both as a person and an artist. I’m interested in a handful of pioneering artists such as Alan Kaprow, who describes an artistic practice that blurs into everyday activity; the question is to see where art stops and life begins. Linda Montano, especially, is an artist who exemplifies that life can be art, and that art is about a state of focused intention and presence. She consistently explores performance as a spiritual endeavor. Her piece 7 Years of Living Art + Another 7 Years of Living Art = 14 Years of Living Art, lasted from 1984 to 1998. During this time she developed an elaborate, durational, concentrated piece based on the yogic chakra system. Her desire is to live more consciously and in a state of constant awareness. Inspired by these artists who were committed to eliminating the boundaries between art and life, my exploration of the boundaries between life, art, and spirituality grew into an association, from 1992-2007, with a traditional Sufi-Islamic religious order from Istanbul, Turkey that has a branch in the San Francisco Bay Area.

This religious order is characterized by a strict program of training and attaches a great importance to dreams, which are considered a form of guidance along the mystic path. For me, this spiritual path mirrored the focus of self-transformative art. It supported conscious intentionality as a potentially beautifying and aesthetic project, particularily in its liturgical rituals. I fell in love with the Sufi notion of adab, an Arabic word meaning something like a combination of chivalry, right action at the right time, manners, and sensitivity. I wanted to apply this ideal to myself and saw its manifestation everywhere. My aspiration for right action at the right time lead me deeper into devotional practices.

There are Islamic hadiths (sayings of the Prophet Muhammad) that communicate the importance of the Qur’an. I heard one interpretation of a hadith that states the Qur’an is like a creature, and after you die it will testify on your behalf because you tried to be close to it. It acts as an intercessor or witness to your love. Abu Umama al-Bahili wrote:

“I heard Muhammad, the Messenger of God say, ‘Recite the Qur’an, for on the Day of Judgment it will come to intercede for its companion.’ ”

A hadith recorded by At-Tirmizi declares:

“Whoever reads a letter from the Book of Allah (God), he will have a reward. And that reward will be multiplied by ten.”

‘Aa’ishah (one of the wives of the Prophet Muhammad) relates that Muhammad said:

“Verily the one who recites the Qur’an beautifully, smoothly, and precisely, he will be in the company of the noble and obedient angels. And as for the one who recites with difficulty, stammering, or stumbling through its verses, then he will have twice that reward.”

How could I go wrong? I always imagined the Qur’an, shouting out on my behalf and cheering me on, and I believed, insh’allah (God willing), the Qur’an would be there for me.

In my dream I am speaking in Arabic. It is all jumbled up, in correct tenses and words, but I am speaking it and thinking in primitive Arabic phrases. I am a dragon tamer, and you use the Arabic language to tame dragons. The only other people in the past who knew this were wizards. If you chant long enough in Arabic, the dragon is hypnotized and will not harm you. I want to say “he has” in Arabic, but instead, I say “you have,” and then I correct my mistake. I can see the sentence very clearly, and then I say it wrong again and promptly correct myself.

By 1998, I decided to improve my reading and recitation of the Qur’an, and for the next six years I took classes in Modern Standard Arabic and in Qur’anic Arabic. I entered the world of Qur’anic recitation, an art form highly revered by Muslims. Learning Arabic to understand the Qur’an became my art, in contrast to my Western avant-garde art education and exhibition record. I memorized surahs (Qur’anic chapters) by copying them over and over as pen and ink drawings that I kept to myself. These memorization sheets became similar to calligraphic drawings and improved my Arabic writing. The writing itself allowed me to see and pronounce the letters and words more clearly and made the memorization process more interesting. The drawings were like prayers or meditations because I would say the ayat (verse from the surah) and write it at the same time in order to memorize it. My plan was to study the Qur’an with love.

In 2003 I relocated, with my then husband, to the Middle East: first to Cairo, Egypt and then to Sharjah, United Arab Emirates. Part of the reason we stayed in the Middle East was to improve our Arabic, specifically for Qur’anic recitation. By the end of my stay in Cairo, amazingly, I noticed that I could look up Arabic word roots in the dictionary more easily, and I began to catch a glimmer of meaning, directly, as it is in Arabic, not from translation.

In my dream there is a voiceover; it speaks about the Prophet, about his fitrah (his nature, character, or natural inclination). I catch a glimpse of him, a kind of flicker, and his appearance corresponds with the narrative of the story. I wake up and ask God, “Did I really see him?” I go back to sleep and have another dream: this time the voice says, “He loved bread and honey.” I see the hands of a man eating bread and honey. (It is the Prophet’s hands.) We all eat bread and honey. Later in this dream, I am in the mosque, and it is time for the call to prayer. I give the call to prayer in a confident, clear voice, and people soon arrive and are given a meal.

By 2006, I could read some passages and understand a basic level of meaning. It was thrilling. But at this point in my journey, something had changed. My faith, passion, and enthusiasm for Islam were under extreme duress, severely tested in part because of derogatory and humiliating words and actions that I constantly suffered as an American Muslim in the Middle East. My naivety was exposed. The Ummah (Community of Believers) had serious problems with me. I was subjected to a litany of criticism, prejudice, and commentary about a scope of issues such as my hair, my apparel, my race, my nationality, my marital and family status, my gender, and my knowledge of Islam:

Why do you wear hijab?

Your hair is sticking out, that is haram.

You should cover your neck.

Why don’t you cover your hair?

Why do you cover your hair?

You must cover your throat, too.

Cover your arms and legs.

You wear your scarf like an Arab.

You wear your scarf like a Turk.

Your scarf looks funny.

What is your nationality?

You are a foreigner–no foreigners are allowed in the mosque.

Are you American?

Why did you invade Iraq?

What do you think about Israel?

You are American, I must kill you, ha, ha, just kidding.

Are you Muslim?

When did you become Muslim?

Why are you Muslim?

Are you really Muslim?

Are you Muslim like we are Muslim?

I didn’t know there were Muslims in America, alhamdulillah.

Are you married?

Is your husband Muslim?

Is your husband an Arab?

Is your father or mother a Muslim?

Is your family kuffar?

Do you have children?

Why don’t you have children?

You must not like children.

White women are less fertile.

We don’t have a prayer area for women in this mosque.

You are a foreign woman, so you can’t enter this mosque.

You can’t pray in front or outside–people may see your behind.

You cannot pray while you have your period.

If you are on your period, you cannot enter the mosque.

Do not do wudu’ over here, this is for the men.

Women are not allowed over here.

The women’s entrance is over there.

Women may only visit the Prophet’s tomb Thursdays 1 to 4 PM.

You must sit with the women.

Stand over there, with the women.

Sit in the other car, with the women.

Everyone move back, our prayer lines are too close to the men.

From this experience, I realized the hard truth about fundamentalist Islam. My California community claimed that Sufism is the kernel of Islam and that the Shari’ah (Islamic Law) is its protective outer shell. The promise of Sufism is the realization of transcendental, compassionate, divine love. But the truth for me was that Sufism became camouflage for obfuscation, judgment, and antagonism. When I returned to the United States, I realized that none of the mystic sugar spoon-fed to me would keep the deeply rooted politics of Islam from bitterly emerging. Especially, as a woman. Love for my religion would never change my role and status. I would never be permitted to freely recite the Qur’an in public, to pray near the front of the mosque, or to give the adhan (call to prayer). No matter what lip service my group and I paid to our Sufi ideals, we were always skirting around the slippery slope of Islamic orthodoxy and global politics. These and other conflicts left me spiritually exhausted.

In my dream I am praying and there are people talking to me, criticizing the way I’m dressed, my hijab, and my looks in general. I try not to listen to them and tell myself that no matter what they do, I have to keep on praying and not let them distract me.

While waiting for me to “get better,” my teachers lost patience with me, and my behavior was not measured by ordinary standards: after 15 years of practice, I was told I had not learned anything. “Why can’t you be like you were?” they chastised. One teacher condemned me as a disappointment, another concluded I was acting out, and yet another declared, “how could such a huge, ugly ego be inside such a little, beautiful woman?” I was accused of disloyalty, stupidity, pathology, and of being unreasonable. These statements bordered on declaring me an apostate (ridda in Arabic) or guilty of being a murtad milli, a convert to Islam who leaves. (In some Islamic countries these charges could cost me my life.) For my troubles, I was shamed and humiliated. During this trial I reflected on another hadith, “Allah is beautiful and loves beauty.” If my teachers had determined I was ugly inside and that my search was a failure, then what about my standing with God? Where was this all going? Some of my spiritual brothers and sisters said, “to Hell.”

In my dream I am on an outing and we go to a mosque for an activity. About halfway through the event I realize I forgot my headscarf and freak out. During intermission I leave to find it; when I come back my teacher is upset that I hadn’t asked permission to leave. I help clean up and as we leave, I break down completely and tell one of my sisters about all my mistakes. I am especially upset about the fact that I forgot my headscarf. I wake up crying, and there is a deep pain in my chest because of this dream and all my mistakes.

There are many Sufi stories about saints asking God to reveal the true nature of their internal hypocrisy and insincerity, and perhaps my teachers were honoring me by unveiling my truly corrupt nature. Abu’Abd al-Rahman al-Sulami al-Naysaburi states in The Stumblings of Those Aspiring (Zalal al-fuqara):

“I heard Abu Zayd ibn Ahmad say that Ibrahim ibn Shayban said: ‘Allah bestows no greater honor upon any of His servants than the honor of showing him the abject nature of his nafs (ego-self), and Allah abases no servant with greater abasement than when He veils him from the abject nature of his nafs.’ ”

In the Malamtiya Sufi tradition, Hamdun al-Qassar, when asked the true meaning of Sufism replied:

“Sufism is made up entirely of adab; for each moment there is a correct attitude. Whoever is steadfast in maintaining the correct attitude of each moment, will attain the degree of spiritual excellence, and whoever neglects correct attitudes, is far from that which he imagines near, and rejected from where he imagines he has found acceptance.”

Unfortunately, I couldn’t live up to the standards and expectations of what I had once profoundly desired. My life had evolved into a crippling, unhealthy double bind. The borderland between life and art had become a no man’s land.

So, I don’t know if the Qur’an will speak on my behalf. But I see these memorization sheets or drawings as a documentation of my 15-year quest for spiritual growth. For me, they are personal relics that I’d like to share because I’m interested in the problems that they represent in the life-art paradigm. The implication is that when art is life and life is art, then the critique of its success or failure is psychologically intrusive, and cuts deeply.

Maybe boundaries are necessary, and since these events, I’ve taken refuge from defining my spirituality. As the proverb says, “Good fences make good neighbors.”

Some of my former Muslim friends consider the drawings haram because they do not conform to the rules of Islamic calligraphy and may distort the meaning of the Qur’anic passages. My response is that although my handwriting is problematic, I consider the moment of mark making to be where life, art, performance, and worship crystallize.

In my dream we are in an art show. People walk through the rooms; we are doing performances or conceptual art. At the end of the day we participate in a little march. Our first outfits for the march are 1950's-type dresses, black “Jackie O” sheaths that my friend says look too nun-like, too much like real religious clothes. We change into loose-fitting black t-shirts and long skirts, and we wear our tesbeh (prayer beads) underneath it all, as a secret, in case something happens–if we die we’ll be wearing our tesbeh. We leave the house very excited, we carry musical instruments and laugh, happy; we have accomplished something. Here comes the celebration! Later in this dream, I am wearing my headscarf and performing in a heavy metal band. I convince them that I can be in a band and still be a Muslim: it’s not a problem. After the show, I am sitting comfortably and smiling, someone touches me quickly and shyly because they want to touch someone who has had a dream of the Prophet.

(3) COMMENTS

You are walking and living the life of your grandmother before you and her grandmother before her. So much similarity in their search for artistic expression, and the standards and expectations put upon them. Do you see that?

Thanks so much for sharing, this is a truly an amazing statement and passionate. I inspire by your arabic writing and spiritural, I wish to walk in your foot step.

love and salam from your hajabi muslim student…

My wife travels to Morocco, encountering questions related to her intentions in helping mostly illiterate Berbers in the SW. Nothing compared to what the author describes. Obviously a brave, strong woman.

Jim LHeureux • June 02, 2012