Feature: Reviews

Glasgow International

- Glasgow International Festival of Contemporary Art

- Tramway, Glasgow, Scotland

- April 22 - May 22 2005

This Peaceful War and The Jumex Collection

Glasgow International Festival of Contemporary Art

Tramway, Glasgow, Scotland

Curated by Francis McKee

April 22 - May 22 2005

“What a world! What a world!”

The Wicked Witch of the West, from The Wizard of Oz

Glasgow International is the city’s first festival of international contemporary art and in this launch year incarnation is an attempt to lay foundations for future years, working towards the development of something significant and substantial. It reflects the commitment of the city’s artists and organizations to developments in recent art and outwardly adds to the city’s reputation with the international art scene. The festival has attempted to highlight curatorial diversity and organic processes rather than impose any rigid thematic structures.

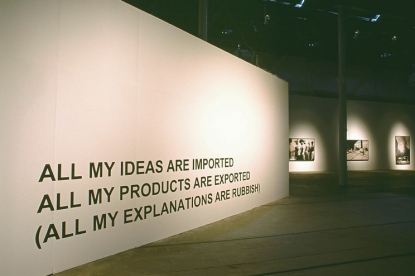

Within this template the festival has offered up, among a wide array of projects, installations and presentation, new work from New York-based painter Spencer Sweeney, a new installation from the iconic Barbara Kruger, the sculptural bewilderment and garish pop assortments of Rachel Harrison, a full-on clash of innocence and evil in When The Sun Goes Down, featuring the Chapman Brothers and Douglas Gordon, Monika Sosnowska’s M10, which subverts familiar territories by isolating features and emblems of institutional aesthetics, and Gifts of Sound and Vision featuring five artists who summarize an overview of recent developments in artist’s video and filmmaking. Three large-scale groups shows, Campbell’s Soup, Risk, and The Last Chickens of Sainsbury explore, among other things, the notion of artistic reputation and association, value systems and intellectual commodities in the age of information abundance and creative action, radical art practice and social inclusion in political culture.

Glasgow International has formed a new way for the city to see itself within international contemporary art, creating a vivid sensibility that reinforces Glasgow’s reputation as a player within the wider visual art culture and preparing with some energy the foundations for future development. In a way it is a model of itself, a prototype that indicates what might emerge, what might occur. It has been about creating dynamic points of interest across the cityscape, which miniaturizes and summarizes emergent practices and established methods and approaches. Given time, space and both financial and intellectual investment, it will grow towards becoming an important destination.

Glasgow International coincided with the launch of Map magazine, Scotland’s new international art publication; Map’s intention is to define the evolution of recent art practice in Scotland in the context of international art. It is both a celebration of Scottish art and artists and a functional engagement connecting with artists and exhibitions, practices and dialogues, intentions and products globally. The title “Map” describes boundaries, evolutions, ownerships, territories and navigations. Map describes power, politics, landscapes, terrains and highlights our current thinking/anxieties on how the world is and how it has shaped and is shaping itself. It will examine how we have become simultaneously suspicious, fearful and energized by global movement, how we have become global tourists and agoraphobics, how we have become witness and participant in wars on land and their commodities, how liberties of individuality, economy, personality and psychology have become capital diverted to support a climate of powerlessness, overprotection and constraint. This kind of thinking is one possible route within the terrains described in the exhibition This Peaceful War.

This Peaceful War focused on landscape, history, politics and power. The artists took diverse positions, demonstrating, for instance how landscape can determine history and politics and likewise how politics and power can shape the landscape. Many of the works touched on issues of property, poverty, pollution, obstruction and the tensions that can exist between tangible possessions and intellectual property.

The Jumex Collection, based in Ecatepec, just outside Mexico City, began in 1997, when Eugenio Lopez, Director of Grupo Jumex, the leading juice company in Mexico, began collecting artwork from around the world. The collection now comprises over 1200 artworks from many leading contemporary artists; it is part of the broader Jumex Foundation, which is increasingly well regarded for helping to create and support a dynamic visual art scene in Mexico.

Doug Aitken’s film installation The Diamond Sea (1997) records, all-National Geographic-like, a journey through Diamond Areas One and Two within a 70,000 square kilometer area along the coastline of the Namibian Desert. This area contains the world’s richest diamond mine, and has been beyond public access for almost a century. Aitken’s documentation was only permitted after a long bureaucratic process and shows a paradoxical landscape.It bears witness to both massive industrial exploitation and natural wilderness with an energized, cinematic-style overview revealing its almost total abandonment. This is a lonely place, populated by industrial fencing, enormous land shaping machinery, and surveillance devices. Aitken’s camera drifts through fences, floodlights and dilapidation, cuts across enormous, silent, shifting desert, and focuses on the dry nothingness a million miles away from the glittering tiaras, engagement rings and hip hop “bling bling” of rocks that decorate people with status, wealth, and vanity. Aitken’s film installation, shown across monitors and projections in a cold secluded box, is a breathless, hot work within a politically, economically and culturally hot vista. It’s the blistering sun in the opening sequence of The Exorcist or the solar flares exploding over the title sequence of the Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

Similarly situated within the desert but rooted within more oblique commentary is Francis Alÿs’s When Faith Moves Mountains (2002). Responding to the political turmoil of the collapsing regime in Lima, Alÿs persuaded 500 volunteers in a poor shantytown district to shift a giant sand dune approximately four inches. It is myth at work and in conception, as well as the process of making “land art for the landless.” The film screening was accompanied by documentation (e-mails, faxes, newspaper articles and the like) showing how this work was initiated, created, and left. It documents the myth in progress, as well as the actual movement of the dune; the work is then entrusted to its audience and participants in the knowledge that they will distort it as they convey it to the public arena. Alÿs’s work seemed absurd at first, a pointless exercise recreating what nature will do anyway. But on closer inspection it is an investigation into the community and its shared experience, the creation of storytelling and recounting, and an investigation into the realities of faith as a constant within economical and social flux. Alÿs seems to do nothing really well, and while this work is about a remarkable pursuit (miraculous even) it becomes in a way an obstruction to the true desires of the community it portrays.

This sense of social obstruction is extended further in one of Santiago Sierra’s performance projects where he had a white lorry maneuver itself across Mexico City’s main highway, creating utter mayhem within the city’s already over-congested freeways. This is the utopian dream gone into disillusion, anger, frustration and immobility. We see on a badly-made video the traffic jam that follows from the positioning of the truck across the freeway; we see the traffic building up and sense the similar build up of human rage and exasperation. The truck intervenes only for a few short minutes, but in that time demonstrated how our complex systems can easily be dismantled and pointed out the underlying delicacy of much human pursuit. Elsewhere Sierra shows his project 8 Foot Line on Six Remunerated People (1999) in which six unemployed men where given $30 to be tattooed with identical tattoos, when they stand together, form an 8-foot line across their backs. There is a tension here between the obvious exploitation of paying paltry sums as compensation to be permanently marked in the name of art and the worth of the final image which will fetch a not inconsiderable sum in the open art market. It is also a reflection on a minimalist art style, austere in its conception and remote from more worldly, human concerns. Similar tensions exist in Eight Remunerated People (1999)whose titular humans were paid to stay inside of cardboard boxes. Situated in a semi-occupied office building in Guatemala City, eight boxes of residual cardboard were made and installed equidistant from each other. Eight volunteers were paid $9 to sit unseen inside the boxes for four hours; the project was abandoned after 3 hours due the excruciating heat. Here the tension exists between a brutalist, purist modernist aesthetic and a demand on the participants to endure. It speaks at the same time of negation of dignity in housing, work and need. It is a brutal work, revealing through anonymity the degradation of humanity via the unchecked pursuit of capitalism and its consequences. It speaks of some kind of human pollution hidden behind cheap materials, economic fallout and formal approaches. This is disorientation on a very human, intimate scale.

Also disorienting, but on a vast scale, is Melanie Smith’s vivid, mesmerizing Spiral City, a 60-minute film loop video projection which shows a breathtaking aerial view of the vast urban expansion of Mexico City. The title alludes to the American artist Robert Smithson’s celebrated Spiral Jetty and his essay “Aerial Art”(1969). This is a work about shifting perspectives, about surfaces and illusions, about the city as abstract and illusive. But it is more than this. It is an examination of a city in trouble, in real peril. In this enormous and beautiful work, the viewer glides across tthe huge city. But there is real danger to be sensed. We know Mexico City struggles to hydrate its population as the water table beneath the city shrinks, we sense the overwhelming pollution as it invades the very genetics of the city, we see the absence of a natural environment in favor of concrete and cars. It is then we realize that we are watching a horror movie, and as with good horror films we are both intoxicated and repelled by the tensions and violence. The film is then about escape, this is not a panoramic gliding celebration of this sprawl; it’s a document about removal and survival. This is a dry work: the viewer comes away claustrophobic, malnourished and dehydrated, in need of sustenance. Which comes in the form of Minerva Cuevas’s Mural. This site-specific wall drawing opens the debate on theft, rebranding, recycling and law and copyright, specifically into the natural resources that have stimulated the exploitation of Mexico and which continue to be the motivating force in the political struggles over national territories. Here we see an array of plants and fruit displayed in relation to visual references on the merger of biotech companies Monsanto and Seminis; these bring to mind the issues of ownership of natural resources, where imperialism takes the form of laws and patents on foodstuffs depleting the future of ecologically rich nations and undermining the economies of already unstable, struggling poor countries. Cuevas’s elegant work is incredibly beautiful, illustrative and painterly, and it forms a contemporary echo of Mexico’s long-standing relationship to the mural as artwork and political manifesto. It’s also an anti-GM graffiti, which reminds us that little of what think of as personal property, private memory, accessible natural resource, or national emblem remains to be called so. It’s all been licensed, patented, privatized, bought out, exported, imported and redistributed.

Dealing with personal mental landscapes and terrains, while illuminating the institutions that surround them, Mike Kelley shows a sculptural mobile and drawing that touch upon the phenomenon of “repressed memory syndrome.” These two pieces are visual recollections of educational buildings from his past. He did not revisit any of the sites in their production. Only later, when he did return, did he discover how little he had remembered, providing an opportunity to explore the voids in his memory and perhaps show where, why and how these voids had come about. Kelley is interested in popular understandings of schizo-theories and how prevalent they have become. Repressed memory syndrome, stories of abuse, sexual, satanic, ritualized, etc., and UFO abduction create pressure to distrust personal experience and history. How institutions assist in creating this distrust is not fully articulated, but Kelley’s piece leaves viewers with the feeling that they contribute to a sense of uncertainty in defining ourselves and our histories.

Another institution is at the heart of Anri Sala’s Arena (2001), which shows the decline of an abandoned zoo in Tirana following the economic depression of the 1990s. Traces of the former Soviet Union disappear, while the zoo falls into utter decrepitude and the city encroaches onto its boundaries. This is a sad and fearful work; the ‘wild’ animals are seen, still incarcerated, while stray dogs circulate the cages, blurring the distinctions between inside/outside, private/public, and foreign/national. The video work is a strong metaphor for the state in decline following the dismantling of the Soviet empire.

This Peaceful War is a map of people, politics, narratives, histories and forms of power in states of flux and tension. Its focus is primarilyy the landscape yet it reveals the tensions in any public or private state; the exhibition space that it is presented in is not immune to similar tensions and was recently under threat from a plan to turn its status as an exhibition venue into a rehearsal space for a local ballet company. This plan, widely criticized by the local visual arts community, has been radically revised, but the exhibition space may still be compromised. This is a large, important space, which has a remarkable history in showing a broad range of significant group and solo exhibitions. This Peaceful War shows power, history and politics encroaching on the landscape and public domain; it is about how politics and power devise obstructions, interventions and pollutions that define the modern world. It seems an interesting dynamic that this exhibition is showing in a space that is itself facing its own war between its function as a public contemporary art exhibition venue and a private space for the rehearsal of traditional high culture ballet productions, and therefore fighting a battle between accepted and popular art forms and critical examinations drawn from a wider international cultural context.

Information about the exhibitions can be found at www.tramway.org and www.glasgowinternational.org