Feature: Essays

Identity Fix: The Double Talk of Lynn Hershman

Once Lynn Hershman hit upon her story, she stuck to it. That story is the story of a body with more minds than it knows what to do with, or of a mind manifesting through several bodies. Time after time, Hershman’s tale of multiplicity unfolds, resolves and concludes, only to return in a new form with the next wave of work. The tributary themes of her work — memory, voyeurism, surveillance, seduction, and authenticity — flow from the condition of multiplicity. How can one remember if there is no “one”? What are the boundaries of a “self” and how are contacts between selves negotiated? What does truth mean when realities proliferate? (“I always told the truth,” she whispers in the video First Person Plural, “For the person I was.”)

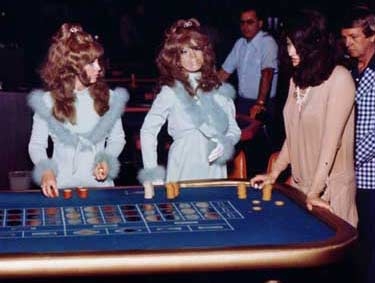

A random sampling of Hershman’s work shows the persistence and the evolution of her theme of multiplicity. There was an early episode in 1968, when she assumed the pseudonyms Prudence Juris, Herbert Goode, and Gay Abandon to write about her work. In retrospect, the act of creating the personalities seems more fundamental to her oeuvre than the work they reviewed. In the 1975 work Lady Luck she took an actress and the actress’s cast-wax effigy to Las Vegas to play roulette. (The effigy bet via random numbers recorded on a tape player in her chest and parlayed $1000 into $1640. The actress turned $1000 into $40.) By 1978 Hershman was near the climax of the persona performance Roberta Breitmore, in which she created a social identity as a work of art. In 1988 she was making Deep Contact, an interactive videodisc that incorporates the viewer as one of the minds governing the body in the narrative. By 1998 she was doubling museum visitors with Internet avatars in both “real” and “virtual” space as part of Difference Engine #3.

Hershman’s media include wax casting, installation, performance, photography, video, film and interactive media. Through all the years and all the forms, her story of multiplicity multiplies. It’s told with varying degrees of resolution; it’s told as fiction and as fact, as the story of a victim and the story of a victor, as the story of an individual and the story of society. As Hershman says in First Person Plural, “All these stories are related.”

Double Dealing: The Counterstory

Art is my survival weapon. It has allowed me to transcend the presumptions of my destiny.

— Lynn Hershman

It’s no ordinary story, this story that is not used up but loops endlessly through variations. It’s a narrative that philosopher Hilde Lindemann Nelson calls a “counterstory” — a story that resists an oppressive identity and attempts to replace it with one that commands respect. “Identity,” for Nelson, is the interaction of a person’s self-conception with how others conceive her, a “complex narrative construction consisting of a fluid interaction of the many stories and fragments of stories surrounding the things that seem most important, from one’s own point of view and the point of view of others, about a person over time.”

Because identity is social, a “fluid interaction” between self and others, it involves inputs from multiple perspectives. Some of those inputs may impede an individual’s ability to act on and express her own view of who she is. Nelson points out that in the course of normal social life, people assign qualities to others based on the groups to which they belong (“Americans are independent”). When these assumptions are based on harmful stereotypes of a group (“black men are sexually predatory towards white women”) and restrict individual freedom, they become oppressive — damaging to the individual’s identity. But because identity is a narrative, there is the potential to “repair” the damaged identity by telling new versions of the story to oneself and to others — counterstories.

“My destiny as a battered and horribly abused child was not to be a survivor,” says Hershman. Finding a counterstory was a matter of life and death for Hershman, but it was no simple matter. To be effective, says Lindemann, a counterstory must “aim to alter the oppressors’ perception of the group” and, when necessary, an oppressed person’s perception of herself.” Over a period of years, Hershman assembled a workable counterstory, one that challenged the oppression of women and restored the sense of self-worth that had been shattered in her childhood. Through her art, she amplified it into socially resonant metaphors. In this process, she challenged the conventional narrative of the unitary self struggling towards self-knowledge (bildungsroman). Resisting social and aesthetic pressures to conform to a singular identity, she gave form to an alternative conception of self as multiple.

Double Dare: Challenging Others’ Perceptions

We started doing performance because it was easier to get access to personal subject matter through performance.

— Judy Chicago

Although themes of doubled and fractured personalities are present in Hershman’s work from her earliest efforts, works such as Self Portrait as Another Person (1971) do not, on their own, function as counterstories because they do not “alter the oppressors’ perception of the group.” But Hershman came of age with the civil rights struggles of the 1970s. “I remember thinking then what a great time it was to be alive — the Black Panthers and the Civil Rights movement were each fighting for freedom and dignity. They became my models,” she told interviewers Moira Roth and Diane Tani. Hershman gradually began to interpret her experiences in political as well as personal terms.

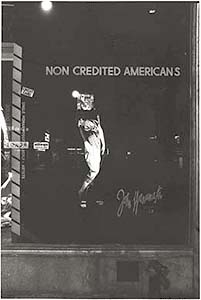

Hershman was introduced to activist art in 1973 by her work as project manager for Javacheff and Jean-Claude Christo’s Running Fence, which involved organizing in the community to gain political support for the work. At the same time that she was manifesting Roberta Breitmore, a personality strongly colored by her private experience of oppression, she also began to create images expressing her increasing awareness of the subjugation of women as a group. Reforming Familiar Environments (1975) presented the madonna/whore dichotomy literally, mixing socialites and prostitutes at the same event. “Because of the dynamics of the evening, every woman was suspected of being a prostitute, and every prostitute was suspected of being a patron,” Hershman recalls. Further relating social class and women’s roles, Non-Credited Americans, a window installation at a department store, contrasted a “privileged” mannequin whose credit card magically attracted goods, with a “poor” one whose credit card had wings that kept it just out of her reach. (Images of a multiracial cast of women, including Hershman, were projected behind the “non-credited” figure.) Twenty-Six Windows, A Portrait of Bonwit Teller (1976) featured, among other scenes, a mannequin literally “breaking out” of her socially assigned role by punching her hand through the plate glass window.

Along with other artists of the 1970s, Hershman began to envision a history of art that included women (the standard art history text of the era, H. W. Janson’s History of Art, mentioned none.) In part of The Making of a Very Rough and (Very) Incomplete Pilot for the Videodisk on the Life and Work of Marcel Duchamp (1979-1984) she set up a “conversation” between herself and Marcel Duchamp, figuratively inserting herself into art history. By the early 1990s Hershman was recording the history of 1970s feminist art on videotape, implicitly and explicitly positioning her work within it. In Changing Worlds: Women, Art and Revolution (1993), Hershman interviewed artists including Judy Baca, Judy Chicago, Suzanne Lacey, Faith Ringgold, and Miriam Schapiro about the beginnings of the movement. Hershman, in her own segment, describes her work in San Francisco as parallel to that of the organized feminist groups in Los Angeles and New York. In Cut Piece: A Video Homage to Yoko Ono (1993), she staged both the Ono work Cut Piece and a discussion of its historical importance by art historians Moira Roth and Whitney Chadwick.

These tapes are active interventions in the narrative of art history, retellings that meet Nelson’s criteria for counterstories: they affirm the competent, moral status of women artists; they replace stories that disregard women with stories that present them as worthy; and they open up the possibility that women artists can act with freedom. They are stories that Nelson’s criteria for counterstories, they can be used “to repudiate incorrect understandings of who they are and replace those understandings with more accurate self-understanding.”

Double Entendre: Healing Infiltrated Consciousness

Self-knowledge always requires conversation. I think it’s generally true in life that to be seen by others is a very important part of knowing oneself.

— Martha Nussbaum

Feminism helped Hershman repudiate others’ incorrect understandings of who she was, but before Hershman could understand herself, she had to tell her story. Until the mid-1980s, she projected it into her art in symbolic form but was unable to speak directly and truthfully of her childhood, even to her therapist, until she began taping the Electronic Diaries (1984-1996). Some of the first revelations she makes are about food — she confesses to the camera that she “ravishes” cookies behind closed doors, dons combat clothes for her “Battle of the Bulge,” and ponders her weight, lack of discipline, and insecure identity. She presents the lived, raw experience that is framed theoretically in these words by critic Rosemary Betterton: “Femininity and the consumption of food are intimately connected and, in women, fatness is taken to signify both loss of control and a failure of feminine identity.”

Although Hershman doesn’t present the politics of weight so analytically, as she converses with the camera she considers the political implications of her personal bind. Finally, she reveals a core secret. At first she tells the story in such a coded, symbolic form that it cannot be understood, juxtaposing clips of an old Dracula movie with her own account of digging into the plastered wall of her childhood bedroom. “I showed this tape to friends, and they didn’t understand what I thought I had said,” she reports. She then faces the camera — although in very dim lighting, as if speaking from the shadows — and tries to state unequivocally what had happened to her: “When I was very young I was physically abused and sexually abused.” Her voice catches before the word “sexually,” but she gets it out. She goes on to connect this most intimate experience with the public realm, specifically relating her experiences to those of Hitler, another abused child. As she speaks, her image is layered with footage of the Nazis, in a visual metaphor for the inherited brutality incorporated into her being.

After forty-five years, Hershman had achieved a full counterstory, a narrative that addressed her inner and outer oppression. What comes next? No counterstory — even one amplified by art — is powerful enough to heal the world, so there is not much danger that Hershman — or the world — will outgrow the need for it. But if the story is effective, as it catalyzes changes they might be reflected in her work.

With this question in mind, a look at the outcomes of Hershman’s major narratives before and after this pivotal Electronic Diary episode is suggestive. By design, the interactive works such as Lorna (1980-84) and Deep Contact (1984-89) have no closure, but the possible endings on offer have a high quotient of violence and disruption. (Lorna, for example, either shoots her television set, commits suicide, or moves to another city.) Of the long, narrative videos, Shooting Script also ends inconclusively and in Longshot (1987-89) the reality of the central female character is more fragile at the end than at the beginning.

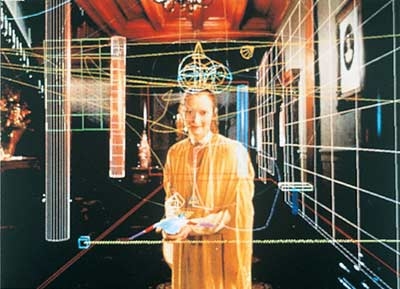

In contrast, the films Conceiving Ada (1999) and Teknolust (2001), which both feature powerful double heroines (doubled and doubled again in Teknolust), have unambiguously happy endings. Emmy in Conceiving Ada “doubles” by giving birth to a daughter; Rosetta and her three clones, in Teknolust, are each coupled with a loving partner. Happiness, for these multiple personalities, does not consist of unification into one voice. Rather, happiness is a situation in which each voice has the opportunity to be heard, to be in relationship with an “other” who pays attention and loves her.

Double Distilled

When a technology comes along that rewards people who are willing to chuck overboard their old selves for new ones, the people who aren’t much invested in their old selves have an edge.

— Michael Lewis

Hershman’s childhood had terrible liabilities, but it made certain things possible. A striking feature of her oeuvre is the way she cycles through media. It is as if her defensive dissociation from her own body translated into a detachment from physical processes, from the “body” of her art. Her mode of operation is the antithesis of modernist “truth to materials.” Hershman has truths she wants to tell regardless of materials. She’s not insensitive to formal concerns and consistently rhymes her narrative with her imaging, as in Binge where she folds and stretches her taped image while she talks of distorted body image. But formal elegance is not the point for Hershman. She openly acknowledges the crudity of the diary tapes within the tapes themselves, at one point venting her frustration over technical difficulties. That frustration, however, doesn’t stop her from periodically chucking her technique overboard and tackling a new medium.

Her restless pursuit of new methods has made examination of her work as a whole difficult. Hershman tends to appear on critics’ radar when she enters their area of interest, and disappear when she moves on to a new medium. But when her work of the past four decades is surveyed, the logic of her development is clear. In First Person Plural, she says “I lost my voice and it’s taken me nearly forty-five years to get it back.” Given that her drive is to make her voice heard, her trajectory through media makes sense. Each shift in technology expands the number of people within reach of her voice. Sculpture was limited to the visitors to one venue; persona performance expanded the audience to anyone walking the street; video reached viewers in the European nations where her tapes were broadcast; film brought a larger audience in the United States, and the Internet work is available worldwide.

Hershman’s oeuvre as a whole can be understood as a counterstory told over time with increasing clarity and force. It acts as an effective agent of transformation for Hershman personally and also, potentially, for those who are touched by her art. Through the telling of the counterstory, multiplicity, at first a wound and a defense against unbearable reality, becomes a fruitful condition.