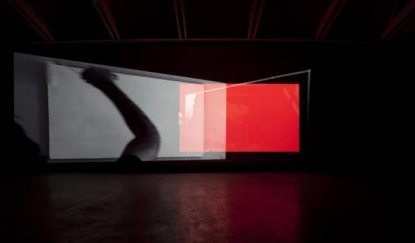

Vesa-Pekka Rannikko, Exterior view of video installation And all structures are unstable, Venice Biennale 2011

Vesa-Pekka Rannikko, Interior view of video installation And all structures are unstable, Venice Biennale 2011

Urs Fischer, detail of Untitled (2011). Designboom has posted

an excellent suite of images of Fischer's installation here.

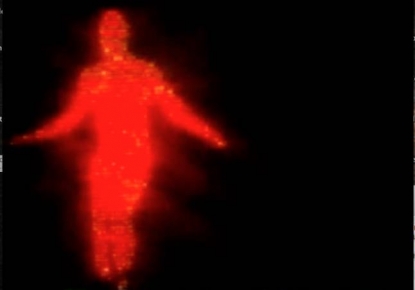

Desire Machine Collective (Sonal Jain and Mriganka Madhukaillya), detail of still from Residue (2010/11)

Exterior of the Arsenale, a manufacturing complex founded in 1104 to supply the Venetian navy during the time of the Venetian Republic.

Stilleben (2011), a sculptural ensemble by Katharina Fritsch,

grouped the artist's name saint and Saint Nicolas with

symbols of birth, death, and temptation.

Feature: Reviews

ILLUMInations +

- Venice Biennale

- June 4-November 27, 2011

Of the 83 artists in ILLUMInations, and dozens more showing in the surrounding pavilions, the ten who had me coming back for more were: Allora & Calzadilla (United States/Cuba/Puerto Rico),Yto Barrada (France/Morocco), Desire Machine Collective (India), Omer Fast (Israel/Germany), Katharina Fritsch (Germany), Gelitin (Austria), Jack Goldstein (Canada/United States), Elad Lassry (Israel/United States), Vesa-Pekka Rannikko (Finland) and Emily Wardill (Great Britain). Special mentions go to Urs Fischer (Switzerland/United States), David Goldblatt (South Africa), Christian Marclay (United States), Nicolás Paris (Colombia) and Amalia Pica (Argentina/Great Britain). Wondering how two artists as different as, say, Barrada and Lassry could make the same list? Read on. Works by this group contain, like a chunk of a fractal, the big themes animating the festival.

Premises

Biennale Director Bice Curiger deals viewers two themes in the keynote exhibition, ILLUMInations: the "intuitive insight and illumination of thought fostered by an encounter with art" and "the idea of nations…taken in metaphorical relationship to community." Like the typographically creative title, Curiger's exhibition is self-reflexive, worrying at the historic structure of the Biennale as a festival of nations, and propositional, embodying an esthetic of complexity. Certainties are in short supply; the exhibition is rife with conflicting stories, inconvenient histories, and uneasy yearnings. Occasionally, a work filled with the joy of living flashes through the uneasy, reflective mood.

By choosing a theme for the central exhibition that was relevant to the Biennale as a whole, Curiger created resonances throughout the festival. Vesa-Pekka Rannikko's installation And all structures are unstable, Venice Biennale 2011, was at the Finnish pavilion, but with its themes of creativity and national identity, it could have been a signature work in Curiger's show. The pavilion is a treasured national symbol, designed by the influential Finnish architect Alvar Aalto in 1955. Rannikko leaned pieces of building material, matching the original materials, against the exterior. This economical gesture suggested that the modernist classic was coming apart, beginning to move. Inside, in a multi-channel video, Ranniko painted and repainted the walls; the projections lapped over each other, folding the space into a concertina of ceaseless making and remaking.

Aalto designed the pavilion as a temporary structure, but when his fame made it a focus of national pride, it became "temporary" in name only. Rannikko's reworking, deeply linked to the history of the site, suggested that insight leads to the building of human structures—including nations—which must be rethought and rebuilt if they are to persist through time. Beautiful and concise, the piece reverberated with ILLUMInations.

Present Past

Venice itself is the ghost of a state that persisted for 1,070 years, and ILLUMInations is planted right on top of the grave—when Napoleon conquered the Venetian Republic, he created the gardens that host the Biennale as a sop to the populace. Both Urs Fischer and Katharina Frisch offered sculptures that dramatically, even histrionically, called attention to the impact of Venice past on Venice present, and by extension to the habits of being and thought with which any nation's past ripples its present.

Fischer showed an untitled ensemble of three trompe l'oeil wax sculptures, their uncanny precision suggesting origins as 3-D digital scans. This technical voodoo may be ho-hum by the next Biennale, but it has surprising charge today. Fischer replicated a contemporary artist, Rudolf Stingel, his chair pushed to the side, contemplating a baroque sculpture, Giovanni Bologna's The Rape of the Sabine Women. All were candles, all burning, all visibly headed towards their doom as featureless blobs. In the meantime, the artist sported curly dreadlocks of melted wax, the sculpture kept snuffing itself out, and the chair guttered into baroque curves. The scene was a show stopper, a crowd pleaser, a vanitas for the twenty-first century. It was also a comment on the Biennale itself: contemporary art and power contemplating past art and power, doomed like all things, but in the meantime shape-shifting and meaning-generating.

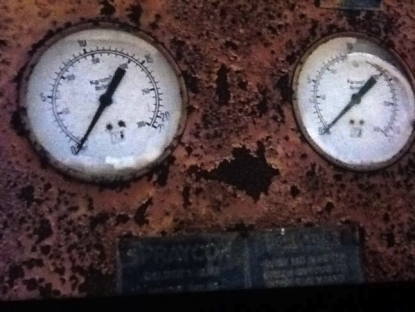

The genre of vanitas reached an apogee in another rich mercantile society, seventeenth century Holland. Might the arc of artistic concerns mirror the might of artists' nations? Is contemplating the fragility of human endeavors a luxury of societies flush with success? Either the answer is "no" or India is settling into place as a major power, because in the Indian pavilion, the 35mm film Residue (2010-11) by the Desire Machine Collective offers 39 compelling minutes of reverie. The establishing shot shows an abandoned thermal plant surrounded by jungle, as isolated as a lost temple. The camera takes us through the plant, lingering over rusty pressure gauges, dripping pipes and scabrous surfaces.

In one passage, the shadows from a corroded, many-piped tank half-conceal a brass, many-armed goddess, the only sighting of a human-like presence. Close attention to visual rhyme smooths transitions through different scales, as when the camera moves from the still goddess to a very alive, many-legged golden spider, and thence to electric lines, delicate and linear like the legs of the insect. Natural and industrial forms merge; plant tendrils reach into the building's openings, rain courses down the walls and beads on the windows. The film echos in mind when one steps out of the Arsenale for a moment and sees ivy squeezing rusty tanks just outside the ancient factory, which, if not for the Biennale, might be abandoned, too.

Continuing down the path outside the Arsenale, Stilleben (2011) an eye-popping ensemble of sculptures by Fritsch shows that not every encounter between the past and present is pensive. Even though the group contains a skull, a traditional vanitas element, it does not suggest comfortable contemplation. Fritsch's saints and symbols are a gang, bits of nasty psychic material breaking into everyday Venice, into consciousness. Insistent matte color both emphasizes and trivializes the forms, making them look like toxic plastic toys. Toys they may be, but they have the super-power of grabbing attention, pushing an amazing stretch of Venetian scenery into the background and commanding their stretch of canal. Within the context of ILLUMInations, they make one think of the various complicated and all-too-human emotions that pervert beautiful national ideals.

Present Present

A turn into the shrubbery leads to Gelitin's Some Like It Hot (2011). During the Biennale's first week, the Austrian collective performed and partied there, as if their installation, consisting of a huge wood-pile, a wood-fired glass kiln, and heaps of broken bottles, were a garden punk club. Tired of mooning around considering the transience of life? Live for the moment! "[Some Like it Hot] is about wasting a lot of energy" Gelitin told interviewer Christian Egger. To that end, they stoked the kiln, which had to be kept going twenty-four hours a day, melted the bottles into slag, banged on guitars, danced and sang.

One can say the piece is based in Venetian history, and Gelitin does, referring to the historic glass industry; one can imply it is about global warming, and they do, referring to dinosaurs; but the strongest impression is of high seriousness meeting high silliness. And a welcome impression it is, too, although it comes with an edge. People must risk rejection to join Gelitin's crowd of friends, similar in age and dress. Having fun together is an effective way of building community—and, as with "nation building," "community building" separates people into sets, including some and excluding others. (In an installation titled Venn Diagram (2011), Amalia Pica comments on a quixotic nation-building attempt to control this process in her native Argentina. There, in the 1970s, Venn diagrams could not be taught in elementary schools, as they were thought to encourage division and subversive thought.)

Back at the Giardini, Jump (1978), an entrancing silent film by Jack Goldstein, offers another sort of anti-gravity. Fixing his lens on an animated neon diver, Goldstein isolated his run off the diving board, twisting and piking into the air. Instead of descending, the diver condenses into a point of light and then bursts into view again, leaping from a new angle. In a show full of works that demand interpretation, this piece asks only for open attention. Heavy and tired as viewers may feel from traipsing around the Biennale, as their mirror neurons respond to the diver's motion, their bodies echo with his weightless freedom. So direct, so memorable, and so "now," although Goldstein died in 2003.

Although it also features dancing, Elad Lassry's film Untitled (Ghost) (2011), is the cool opposite of Gelitin's heat. Lassry opens with a shot of four dancers, wearing yellow or blue leotards and tights. They rub shoulders, forming a group, but move like individuals, adjusting their leotards, blinking, massaging their necks. Twice, in response to some invisible cue, they pose for the camera, smiling, then lapse back into their private thoughts. Then the camera cuts to a bare beige studio, where the dancers are in formation, set to dance selections from Balanchine's "black and white" ballets. (So-called due to their original costuming.)

As their still figures break into the dance, every muscle twitch is subordinated to the choreography; unlike Gelitin's gusher of physical energy, the physicality here is a supremely focused force. The dancers' transition from a pack of restless individuals to a unity was intriguing and it could have been the point. But Lassry has something, or someone, else waiting. The camera moves up and over in a precise right angle, to frame a balcony where a translucent ballerina wistfully regards the dancers. After a long moment, she ballet-walks down the stairs and joins the dance; she fits right in although we can see right through her. What to make of this development (or développé)?

Lassry first became known for fastidious still photographs camouflaged as stock imagery, examples of which hang near the viewing room for Untitled (Ghost).) In them he uses "mistakes"—blurs, double exposures, color tweaks—to startle viewers into awareness of the expectations they bring to the image. In this context, the ballerina's phantom limbs may be simply a significant "mistake," a signal, along with the bright color, that Lassry is taking on the conventions of documentary film. It's an endeavor with political import given the power that documentaries have to shape public opinion. The meeting of art film and ballet may seem like the highest of high-art formalisms, but there's more to Lassry's topic than meets the eye. In From Petipa to Balanchine, dance historian Tim Scholl writes of Balanchine's "black and white" ballets that, "his decision to include visible bodily effort as an element of his choreography…involve[s] the 'inartistic,' vernacular qualities of [his] media in the creation of art."

Just as Lassry uses carefully calibrated physical imperfections to make viewers look, Balanchine cut through the fantasy of traditional ballet to draw attention to the body in the moment. Untitled (Ghosts) might thus be read as a double-barreled jab at enculturated habits of thinking, a way of bringing viewers alive to this dance/film, now, and thus to fresh ways of looking at anything.

Sore points

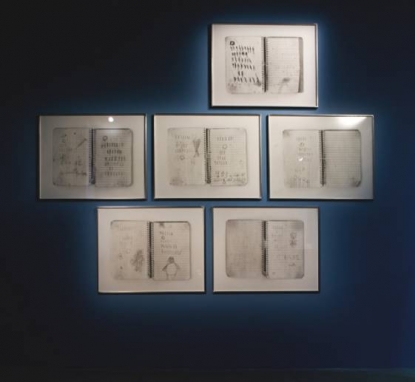

A spirit also inhabits Yto Barrada's photographs The Telephone Books (or the Recipe Books) Fig. 1-3, Fig. 5-8. The suite of eight prints, which Barrada seems to have shown first in 2007, is grouped with other works in an ensemble called My Family and Other Animals (2011), all installed in a "para-pavilion" by Song Dong. The "para-pavilion" is one of four commissioned galleries-that-are-also-artworks in the Biennale, a dramatic, multi-level construct that does Barrada's work no favors. Lured by its mirrors and platforms, I walked right past her work on my first run-through. But although both installations are family-oriented—Song Dong used elements from his childhood home—Barrada's is the one that captures family feeling, which is often the most intimate experience people have of the pressure of the past and future on the present.

The Telephone Books… consists of straightforward, larger-than-life views of four humble-looking notebooks and the crudely penciled drawings and marks inside. It's the caption information that snaps the piece into focus.The notebooks belonged to Barrada's grandmother, who was the illiterate mother of a dozen children, of whom two died. These facts suggest that she had fewer opportunities than most Biennale viewers. The marks are the personal code she invented to keep track of her children's phone numbers, which suggests that she was a resourceful, loving person. The clarity and scale of the prints suggest that her life is worthy of admiration and attention.

Although viewers don't really know her story—the facts given could, in some times and societies, describe a fortunate woman—in the context of the Biennale, Barrada's grandmother represents inventiveness confronting discrimination and poverty with dignity. Which suggests a sore point in the Biennale's meeting of nations: conversations about inequity often seem so…theoretical, if not to say hypocritical, when conducted in the art world's festival atmosphere. It was much remarked that during the opening days a collector's huge private yacht moored at the entrance to the Giardini; what can an event often decried as a party for the ultra-rich offer to someone like Barrada's grandmother?

In the American pavilion, the artist team Allora & Calzadilla tackles a piece of this question in Gloria, a blunt, entertaining group of five works that includes Track and Field (2011), one of the most-talked-about pieces in the Biennale. Allora & Calzadilla turned a 60-ton tank upside down and crowned it with an exercise treadmill. Every so often, an Olympic runner mounts the treadmill and jogs for thirty minutes, cranking the tank treads with an impressive racket. It's a beast of a piece, funny, smart, and political; and the other four works in the pavilion are just as impressive. Using complex mashups of symbolic objects, performances, and audience participation, Allora & Calzdilla pokes fun at American culture's quest for health, wealth, and world domination.

And thereby manages to do America proud. Their critique pulls no punches, but the humor saves the piece from righteousness. These failings are known, after all, to occur occasionally in other cultures. At a time when Chinese artist Ai WeiWei was jailed for criticizing his government, America's official support of Allora & Calzadilla's work made the pavilion a forceful comment on the worst AND the best of American culture. As Curiger wrote in the Biennale's catalog, "For all the criticism that has been leveled at the idealization of rationalist Enlightenment thinking in recent years…it remains imperative to uphold and defend these values, not least in the critical debate over human rights."

Now what

Of course, the problem is usually not with the values but with living up to them. In his video projection 5000 Feet Is the Best, (2010), Omer Fast constructed a potent critique of what happens in the course of "defending freedom," using multiple allegories. The film is built around a documentary interview with a man who operated Predator drones in Afghanistan. He talks about his work and about his pain when he began to think of his "targets" as people. A lazy Susan of other American stories revolves around the interview, cutting in and out of the soldier's tale: two grifters fleecing men in Las Vegas; a mentally challenged man, obsessed with trains, who impersonates an engineer; an American family who, for political reasons, must leave their home forever; and a jittery man who is always about to tell his story to the filmmaker but never quite manages to settle down and tell it. As with a drawing that is the more beautiful because just enough is given for one's mind to fill in the details, Fast engages the viewer with narrative points that ache to be connected into a "view" but can never be contained in one linear interpretation. They circle, refusing to settle—tantalizingly, even irritatingly, alive with meanings.

Fast's entangled tales of conscience, greed, passion, fear, and anxiety play out in the social world; in Emily Wardill's 16mm film Sick Serena and Dregs and Wreck and Wreck (2007) the locus of the scrambled narrative is personal and psychological. Her characters step out of a stained glass window to enact a confused tale of passion and murder. Lurid lighting, ad hoc costumes, and dragging, hesitant speech do as much as any particular plot point to convey their painful emotions; the contradictions between their origins as religious allegories and their excessive feelings flood the film with irony.

The works of Fast and Wardill are similar in creating for their viewers the experience of "cognitive dissonance," the discomfort of holding conflicting ideas simultaneously. Cross-cultural research shows that humans frequently resolve such dissonance by employing blame, denial or self-justification to discredit one of the competing ideas. Avoiding the distress of, say, killing the people one thought one was protecting, by imagining they deserved it, denying it is happening, or claiming there was no choice, is a personal experience that eventually adds up to a national issue.

Throughout ILLUMInations, Curiger chose works that refuse, like Fast's drone operator, to settle for certainty. There as almost as many ways of doing this as there are artists in the exhibition. David Goldblatt's images of South African "criminals," photographed as ordinary people, are formally straightforward but by refusing to assign their subjects a stable social position, stir dissonance in the viewer. And in Classroom: Partial Exercises (2011), Nicolás Paris created the conditions for literally and figuratively exploring different points of view, using a collection of drawing exercises intended to "draw" viewers into conversation. Paris did use the exercises with groups of people, but there wasn't a session during my visit. That didn't mar the pleasure of the gentle installation. Paris used a lovely formal metaphor for learning to look beneath the surface, infiltrating the walls of the gallery with delicately drawn "lessons" sequestered between the studs.

Strategic Viewing

In ILLUMInations' title Curiger made a direct link between scales of human experience so disparate that they don't always seem connected: the individual experience of insight and the group experience of nationhood. The works she chose to develop her theme offer a compelling opportunity think the subject through; because her theme related to the very substance of the Biennale the central exhibition was "illuminated" and expanded by other parts of the festival.

Every visitor to the Venice Biennale sees a different show, curating their own personal festival from the overwhelming number works on view. Philosophically, of course, it could be said that no two viewers ever see the same exhibition, but with a centerpiece exhibition, 89 national pavilions, and sprawling suburbs of official and unofficial collateral events, the Biennale forces the issue. With "only" three days to devote to the Biennale, I targeted works in or around ILLUMInations. Thus I could watch the most intriguing videos two and three times over, discover quiet works I'd overlooked on the first run through, and map the bypass routes around the disastrous but centrally placed Italian pavilion.*

Even so, I reluctantly skipped the long line for James Turrell's installation Ganzfield APANI (2011), having had several memorable experiences with Turrell's works in the past and opting to concentrate on artists less known to me. If this is your first chance to experience a Turrell, get in line. And the only possible argument not to devote a chunk of your Biennale visit to Christian Marclay's video The Clock (2010) is that it will continue to be an internationally celebrated, touchstone work of art for decades to come. It won the Golden Lion for Best Artwork and deserved it. If you frequent a major metropolitan art center, you will probably have another chance to see it in your lifetime. On the other hand, you might want to get started viewing it now—the montage of international film clips, each featuring a timepiece that, when the film is properly synced, shows the current time, repays an extended visit. It is, after all, a twenty-four hour experience.

In the ILLUMInated spirit of holding different views in solution, I link below to other critical responses to this year's Biennale, as well as the festival website. Your own thoughts on the Biennale are welcome, too; share them through the Comment link below.

* The Italian pavilion was just sad. With so many intriguing works calling for attention, I preferred to ignore it. Mark Van Proyen gives a good account of how and why the space was wasted in his review linked below.

Other reviews

Various writers for The Guardian

Gabriella Piccone for Berlin Art Link

Mark Van Proyen for Square Cylinder

Sue Wiliamson for Art Throb

Linda Yablonsky for Artnet

ILLUMInations website

http://www.labiennale.org/en/art/

Venice Biennale website