Feature: Reviews

Kiki: Exhibitions & Bits

- Ratio 3

- June 27 thru August 2, 2008

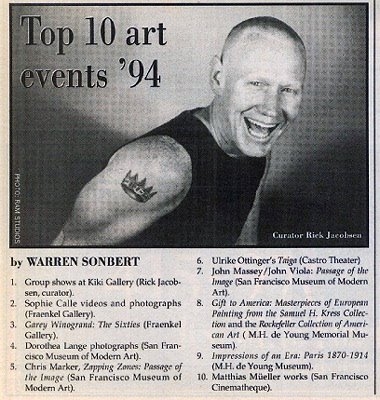

There’s a curtained storefront at 14th and Guerrero on the outskirts of San Francisco’s Mission district that was a central meeting point for artists in the early 1990s. Blue-and-white checkerboard tiles embedded in the stucco façade below the front window are the only physical traces of the former Kiki Gallery, the subject of the recently closed retrospective show Kiki: The Proof is in the Pudding at Ratio 3. Kiki Gallery had a palpable, if largely unknown, influence on the current state of art and queer culture in San Francisco and contemporary art history in general. The show at Ratio 3 hosted original work presented at Kiki by founder and owner Rick Jacobsen (1961-1995). Jacobsen ran the space for eighteen months until complications from AIDS-related lymphoma forced it to close. Curated by writer Kevin Killian and artist Colter Jacobsen (no relation), The Proof is in the Pudding illuminates Rick Jacobsen’s magnetic charisma as the driving force behind a gallery that came to represent an intense period of creative potency and self-representational politics in early ‘90s San Francisco. As a group, the pieces in this exhibition exude a pervasive attitude of assertion into a broader cultural structure that was cultivated through interconnected work in a variety of disciplines.

As an activist, Jacobsen cut his teeth dealing artwork as a form of fundraising for ACT UP benefits. In a 1994 interview for The Other Side, Jacobsen describes the genesis of the gallery: “I’d been working for an AIDS organization, called 18th Street Services, as an outreach liaison … But the bureaucratic system of chasing government contracts left me with a lot of negative feelings. In 1992 I went to visit a dying friend in Italy, where I contracted parasites and since, because I’m HIV-positive, my doctor urged me for an indoor position – to be alone in a park at 2 a.m. might be scary if I suddenly become incontinent. But my agency refused to transfer me. Then, in the midst of all this—attending in one day two different memorial services had a real impact on me—I had an epiphany that I wanted more control in art and performance space – I wanted to reach out to the community on my own. If I couldn’t do anything first hand about AIDS, I could be at least a motivating force in art – perhaps the next best thing.” Taking $900 in severance pay, he rented the storefront at 483 14th Street next to noted lesbian tearoom and performance space Red Dora’s Bearded Lady Café and Truckstop. Started by artist Harry Dodge (known to some as Dinah in John Waters’ Cecil B. Demented) and Tribe 8’s Silas Howard, Red Dora’s shared its back patio with Kiki. On a weekend evening, one could purchase a veggie dog and a coffee in Dora’s, walk about 15 paces down a narrow corridor and through a back room, exit Dora’s into the patio, and take a left into the back room of Kiki.

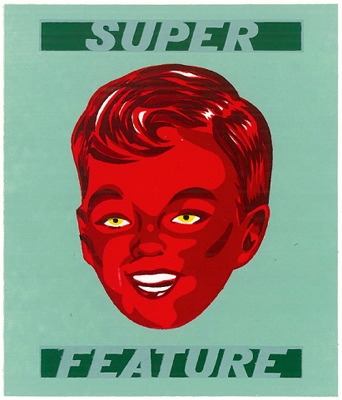

Much has been said about the size of the space at Kiki, the tender mockery of which journalists seem to find irresistible. It has been called “postage stamp-sized”, “no bigger than a postage stamp”, “diminutive”, “cozy”, “very small”, “tiny”, “the size of a small living room”, “a single lane at the world’s smallest bowling alley”. The unassuming size doubtless contributed to a more carefree, jocular attitude that fostered an attitude of experimentation and frivolity distinct from the pressures applied to artists by more formal galleries. As Killian comments in his working memoir about Kiki and Jacobsen, “if it was a clubhouse, Kiki was the clubhouse for the poor boys, and the rich boys were hanging around Fraenkel or Berggruen or Anglim.” The collapse of the power-art-market of the eighties converged with the height of the AIDS crisis in San Francisco, which hit its peak in 1992, nearly ten years after the disease had been named; nobody had jobs, and everyone was dying or knew someone who was. As such, a resistance to physical degradation and social stigmatization through black humor frothed and oscillated along the gallery’s walls. Caca @ Kiki was Jacobsen’s first show, and it defined the darkly irreverent nature of Kiki’s productions; a show about shit, and further, about AIDS, bodies, and mortality. Caca @ Kiki included Scott Hewicker’s educational toy-turd Food Chain, D-L Alvarez’ paint-by-numbers drawing Hunt, and the first in Michelle Rollman’s Velveteen Rabbit series, all included in the show at Ratio 3. In a statement for his show, Jacobsen comments that “in human terms, the cruelties of prejudice, disease, and ineffectual government are enough to cause the occasional utterance ‘Life Is Shit.’ … Pleasingly, the works presented in this exhibition spring from these ideas and others from places deeper and more varied than just the toilet bowl.”

Between Caca @ Kiki in June 1993 and Piece: Nine Artists Consider Yoko Ono, the gallery’s closing exhibition in February 1995, Kiki presented over 150 artists and performers, turning shows over about once a month. Most were group shows, such as Carcass, curated by licensed taxidermist Jeanie M., and Fresh Produce, which included work by Stretcher editor Amy Berk. Bong!, an exciting show of “artist-designed waterpipes”, was co-curated in the summer of 1994 with Alleged Gallery’s Aaron Rose. (“My first sculpture was a bong, back in high school,” remarked contributing artist Nayland Blake.) Issues of High Times, licorice whips, and other munchies were laid out amongst the fully-functioning pipes, while the gallery’s back room was set up as a chill-out pad replete with bean bag chairs and a record player.

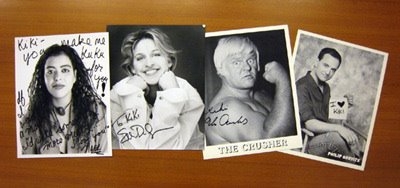

There were several two-person shows, with one artist’s work hanging in the front room and the other artist taking over the back. Catherine Opie’s Portraits showed alongside Jerome Caja’s Toiletwater in April 1994; comprised of 15-plus well-known photographs taken of friends from the lesbian, gay, and transgendered communities, Opie’s show included images of spectral performer Justin Bond and sister artist Caja. Dozens of Caja’s delicate enamel and ephemera-collaged icons (more than 90 listed, more than three-quarters sold) crowded the back room’s walls, while the artist greeted patrons at his opening in burlesque, lounging deep in the suds of a claw-footed bathtub. There was a joint show with Keith Mayerson (Pinocchio the Big Fag) and skateboarding superstar Mark Gonzales in November 1993; Vincent Fecteau (Ben, which included his collaged “cat stacks”) and Clifford Hengst (Reconciled) in March 1994; and D-L Alvarez (Night Of The Hunter) and Chris Johansen (Fantasy Island) in October 1994. Selections from all of these two-person shows were included in the Kiki show at Ratio 3.

Virtually every show was produced with a corresponding catalogue, booklet, or zine. A handful of these were featured in the San Francisco Public Library’s summer 2005 show Out At The Library, including This Is Not Her, a 6”x6” booklet produced for Kiki’s ultimate show Piece: Nine Artists Consider Yoko Ono, and the catalogue for Sick Joke: Bitterness, Sarcasm, and Irony in the Second AIDS Decade. Bookended by images of Lutz Bacher’s Butt Photos, This Is Not Her includes a very funny recollection of Dennis Cooper’s challenge to Ono’s legacy along with other memoirs and homages by writers such as Ann Magnuson, Robert Glück, Bob Riley, and Dodie Bellamy. (Bellamy’s gleeful recollection of Cliff Hengst’s direct action/outdoor performance of “Cambridge 1969” for the opening of Piece is one of many excellent essays about Kiki included in the zine produced for the Ratio 3 show.) Fanged sarcasm and irony hiss manifest in the catalogue for Sick Joke. Festooned with a red AIDS ribbon inverted and twisted into a noose, the essays humorously combat the denigrating effects of AIDS’ social and cultural transformation into a de-personalized, Rent-ified commodity “experience.” And Jacobsen laughs at even this: “Fuck it; today we’re survivors. Enjoy the show.” Of all ephemera associated with Kiki, this catalogue has real resonance and import in communicating to so-called “post-AIDS” generations the painful lived histories that persist against the contrived creation of a patronizing, “tolerant” attitude towards AIDS. In contrast to red ribbons, Kiki and its network of friends offered a space for personal solidarity.

Performance, plays, and readings, too, were an important component of the Kiki scene. 3 On A Match, a play by Kevin Killian, was featured at a July 2008 SF Cameraworks screening of Kiki performances. Actors jockey for space on a platform set in front of the gallery’s front window, entering and exiting scenes from the hallway or the front door. The camera recording the play is cramped, panning from head to crotch to toe, unable to fully recede, not quite able to grasp any one figure in its entirety. Originally shown in February 1994, Killian’s play was one of many different types of live theater shown at Kiki. There were performances by area artist and champion wrestler Jennifer Locke. There were readings about young lust (Retarded: Teenage Stories of Exploded Bliss, with Scott Hewicker and D-L Alvarez) and plays about celebrity psychodrama (Killian’s Life After Prince, David E. Johnston’s Southern Gothic Gone Dollywood). Nao Bustamante performed as an opening act for Aaron Noble’s Man. Hole.; Noble, perhaps best known these days for his paintings and mural projects, began his artistic career as a performance artist in the mid-eighties.

One of Jacobsen’s most successful theatrical ventures was the production of The Joan Jett Blakk Show, also known as Late Nights With Joan Jett Blakk, hosted by the eponymous Chicago drag queen, performance artist, and politician (she mounted a presidential campaign in 1992, and ran against both Chicago mayor Richard M. Daley and San Francisco mayor Willie Brown at different stages in her career). Beginning in February 1994 inside Kiki itself, the show’s tremendous popularity warranted a larger audience space, and later that summer it moved to Josie’s Cabaret & Juice Joint at Market & Noe for weekly presentations at midnight. Billed as “an equally stimulating and surprising mix of smart talk, celebrities, cool music, comedy, and right-on politics,” guests at The Joan Jett Blakk Show – co-hosted with white-trash cooking artiste Babette—included Kiki denizens Nayland Blake, David E. Johnston, and “Matthew and Rejoice” (actually Scott Hewicker and Cliff Hengst performing as an ex-homosexual Christian Rock duo); sex activist Carol Queen; San Francisco Leather Daddy X Irwin Kane; San Francisco Board of Education President and comedian Tom Ammiano; Kiki & Herb, Tribe 8, the Pee-Chees, and John Ginoli of Pansy Division; and “Box-Office Sensation ET the Extra Terrestrial,” among a panoply of other queer artists, musicians, writers, activists, and administrators. Blakk, member of gay black performance group Pomo Afro Homos, was celebrated on the cover of the Guardian’s Pride weekend issue that June. The July 2008 Kiki screening at SF Cameraworks included a portion of the Joan Jett Blakk show; Blakk presides as “really skinny drag queen” guest Jerome Caja teeters across the stage in a slinky stretch dress and heels, calling to audience members who call back; laughter, against marginalization and death, as relief and tight embrace. (Much documentation of the show exists on videocassette, soon to be transferred to DVD – part of the larger cache of Kiki material held by Kiki artist and ally Wayne Smith.)

The Joan Jett Blakk Show was featured in programming for In A Different Light, a cross-generational presentation of queer art curated by Lawrence Rinder and Nayland Blake at the Berkeley Art Museum during the first half of 1995. The spirit of Kiki and the influence of Jacobsen directly influenced the curators: about a fifth of the artists and writers connected to Kiki were featured in the show, and, as Rinder comments in his essay for the Exquisite-Kiki-Corpse zine assembled for the show at Ratio 3, “Observing the dynamism and urgency of the Kiki scene made me think that the Berkeley Art Museum ought to put on a show presenting this work to a larger audience. … To develop the organizational concept for the exhibition we looked no further than Kiki itself, deciding to create the show out of fortuitous and felicitous seemingly chance encounters among artists and ideas.” Rinder’s essay also invokes the East Village art scene of the 1980s by connecting Kiki to Peter Nagy and Alan Belcher’s Gallery Nature Morte. Like Kiki, Nature Morte was a potent locus of creativity housed in a very small space, and, like Kiki, Nature Morte’s aesthetic ideology was geared less towards marketability as an existential justification than it was towards self-defining social and political identities.

Kiki was one of several artist-run galleries that appeared in San Francisco during the late ‘80s and early-to-mid ‘90s: Gallery LaGreca, 99 Sanchez, ARU, Cheap Art Store, Show N’ Tell, Anti Matter, E’Space Pierrot, Build, The Victoria Room, The Luggage Store Gallery and 509 Cultural Center, and Refusalon (initial founder Charles Linder having since translated his passions into Lincart). Jacobsen himself formally acted as a representative of artist-run spaces by participating in workshops and symposiums such as Capp Street Project’s “Accessing the Art World” in October 1993 and Southern Exposure’s “Making Change: Assessing 20 Years of Northern California Artist’s Organizations” in September 1994.

I asked how Colter Jacobsen came to co-curate the Kiki show at Ratio 3. He remarked that in leafing through the San Francisco Public Library’s archive of Kiki material “I actually got really emotional. I think because I knew many of the names of the people who had attended the escapades of Kiki and at the same time I felt oddly outside of it but looking in, like a ghost. It made me think how [an archive] was representing a trace of a community that once existed. I was also intrigued by the fact that so many artists that I admire first went through Kiki. I don’t know that there was one particular event that triggered all of this but rather a gradual learning experience that to me continually became more and more interesting.” It seems clear that Kiki: The Proof is in the Pudding is the result – the proof!—of efforts by multiple parties; artist Sam Gordon, for example, had been working with the idea of putting together a Kiki show for a number of years, and he passed his efforts toward that end to Killian and Jacobsen. The show has allowed a variety of emotions, ideas, and experiences to resurface, providing for neophyte audiences a picture of the early ‘90s—artistic life, gay culture, activism, pop iconography – that they may or may not have examined.

The show helps us to imagine what early ‘90s San Francisco was like for artists. In his catalogue essay for In A Different Light, co-curator Nayland Blake explains that “This [began] in response to a type of energy and activity around a community of artists. What, then, is it like for artists to be around that energy, that excitement? What are artists doing? … I have thought about those times when being in the world as an artist has meant the most to me; those times when I could feel a presence, a looming joy in the works around me. The early ‘90s were such a time in the queer community in San Francisco; notions that had been circulating began to come together in new constellations. The world seemed full of fresh messages, truths perhaps addressed to us alone, but connecting us to other initiates. … We say that ‘history is being made,’ but it would be more accurate to say that ‘life is being lived.’”

To read Kevin Killian’s working memoir on Kiki and Jacobsen, please follow this link:

http://denniscooper-theweaklings.blogspot.com/2008/07/kevin-killian-presents-kiki-gallery.html

Ratio 3