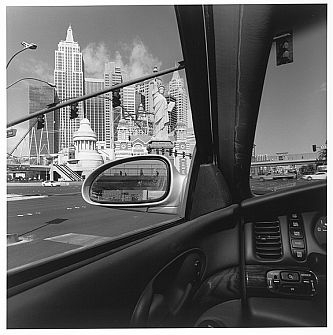

Lee Friedlander, Las Vegas, Nevada (2002) Collection of the photographer. Copyright 2005 Lee Friedlander

Feature: Reviews

Lee Friedlander

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

- February 23 - May 18, 2008

There are more than four hundred photographs in the current Lee Friedlander show at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and its massive catalog includes nearly twice as many plates. Friedlander has been taking photos of mostly the same subjects from the start: windows, buildings, fences, trees, and portraits of friends and strangers. They are all modestly sized black and white prints of naturally lit scenes—everything he is showing us we have seen for ourselves. Which begs the question: what’s special about hundreds of photos of the same topics taken over nearly fifty years?

For starters, none of these photos are accidents. Friedlander is showing off his keen eye for how we look at things, or how we could look at things. We’ve all seen a lone television on in a room, but he’s drawing our attention to what it would feel like if we weren’t so used to having them around. He’s showing us the side mirror view in the middle of the landscape because that’s what we actually see when we look out the car window. He’s asking us to unlearn the ways we block out extra information and see how things really look on the ground. And what he’s found, over and over, is that the world is much more interesting than we think it is.

But there’s more than just showing us how things really look—Friedlander is a master of composing an image. He can make a pedestrian walk into a signpost or float a Coke bottle out a hotel window. He can seemingly add or subtract whatever elements he chooses: reflections, shadows, words, statues. He parks clouds on street signs, splits cars in two while nobody’s looking. He even uses his own shadow to project himself onto his wife’s naked body. He’s using his camera to conjure up layered scenes that seem impossible. But here they are.

Photography offers a perfect tool for expressing complexity without being fussy. In Friedlander’s hands, the result can be so complex as to be almost unpackable, but it’s still an image made in the click of an instant. A photo of Gettsyburg, Pennsylvania is a frenzy of activity, fractured by so many flowering branches as to evoke the violence the scattered war monuments are meant to call to mind. It’s true that any of us could have seen this scene, but make no mistake, Friedlander arranged those branches, he hid the guy on the horse back there and revealed that sad cannon ball just so. Occasionally you find a lucky snapshot that captures something special like this. But luck and magic are two different things. Need proof? Here are four hundred examples.

Following the presentation at SFMOMA, Friedlander will travel to the Minneapolis Institute of Art (June 29 - September 15, 2008) and the Cleveland Museum of Art (March 1 - June 7, 2009)!.