Feature: Reviews

LifeLike

- New Langton Arts

- San Francisco

- June 27 - July 28, 2001

The idea for reviewing a review came out of a discussion I was having with Josh Greene (an artist) over a shared bowl of ice cream. Josh mentioned a review he had read in Artweek magazine that he was particularly fond of. I urged him to elaborate and we discussed what makes one review more engaging than another. I then voiced my principal frustration as an art critic – the lack of feedback (criticism) a writer receives on her work. Between us, we came up with the idea of reviewing reviews, offering the art critic a similar service to that which is provided the artist- a formal analysis of their creative endeavor. Josh expressed the belief that writers and artists best attain critical feedback on their work in the more informal process of face to face interaction and other forms of one-on-one communication (e.mail, u.s. mail, etc.) Since art reviews are generally targeted towards a wider community of readers however, it only made sense that a review of a review be presented in a similar context and made available to a wide readership. It was decided that Josh would review my review for Stretcher.

– Berin Golonu

One might expect an exhibition titled LifeLiketo spur an existential debate about the hierarchy between the naturaland the artificial, one that is posed in films such as A.I. (andBlade Runner before it,) where robots are rendered so eerily similarto human beings in appearance, intelligence, and personality that it becomesdifficult to determine how to assign a value to the mechanical in relationto the organic. That is, if the work in LifeLike was, well, a littlemore lifelike. As it stands, most of the work makes such a tongue-in-cheekcomment about the confluence of the natural and the artificial, like thecampy special effects of a B-rated sci-fi movie, that the nature vs. culturedebate acquires a disconcerting absurdity.

Marcia Tanner noted in her curatorial statement that artists, primarilyduring the 18th and 19th centuries, were taughtto model their work after nature, that the more representational or “lifelike"their work appeared, the more successful it was deemed to be. Nowadays,artists, scientists, plastic surgeons and biotechnology engineers alikehave gotten past such romantic notions. Nature is too unpredictable, toowild, too difficult to control. Now the challenge is not to representnature, but to recreate it in an abbreviated, more efficient manner: geneticallyengineered seeds that are more resilient to disease, bald pets for thoseallergic to cat or dog hair. Never mind that nature “enhanced” by manoften falls short of the real thing—a simple taste test proves thatproduce pumped full of hormones never tastes as good as organic, and whowould want to pet a hairless cat anyway? If someone can make a profitout of it, we can rest assured that there will be a demand.

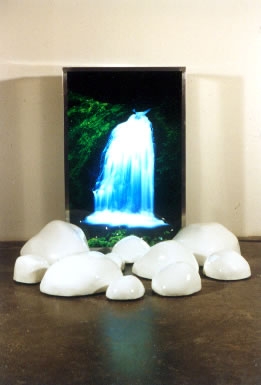

The decidedly low-tech works in LifeLikemake painfully obvious humans’ inadequacy at playing God, callingattention to how our legerdemain falls pathetically short of recreatingthe complexity of nature. It’s no shock, therefore, that Reuben Lorch-Miller’s glorified beer sign (Or is it a screen saver?) sporting the picture ofan animated waterfall doesn’t approximate the monumentality of NiagaraFalls, even if he did choose the right sound track to accompany it. Inthe same vein, the sight of Elliott Anderson’s mechanical, toy-liketortoise lying on its back under a heat lamp couldn’t possibly inspireempathy from the human observer, even if it does have a red blinking lightbulb for a heart. And the notion that Stephanie Syjuco’s computercomponents rendered like 19th century scientific illustrations documentingvarious species of flora could closely approximate the beauty of our naturalworld, even if the artist has digitally grafted natural textures on topof their plastic surfaces, comes across as being slightly farfetched.

The most successful pieces in LifeLike examine the results of ourbotched attempts at reconfiguring nature. Philip Ross spent six monthsgrowing fungus—Ganoderma lucidum to be exact — into shapesthat resemble architectural structures, or in one case, the compositionof a well known photograph by Harold Edgerton. Of course, the growth pathsof the moulds haven’t exactly followed their molds. Various sectionsof the fungi have sprouted antennae that loom disproportionately out ofcontrol, threatening to take over their glass vitrines. These living beingsmight have been nurtured by mankind, but they clearly have their own agenda.And it’s no surprise that Ross’s fabrications, the only “living"beings in the show, are also the most interesting objects on display.

John Slepian’s fleshy mutations offer an evenmore biting critique of man’s interventions in the universal order.Two monitors facing one another display images of tumor-shaped biomorphsdigitally rendered from scans of the artist’s own skin. These knuckle-likeblobs apparently have vocal chords, as they coo at one another throughwhat look to be rectal orifices adorned with lipstick. Is this what thehuman genome project has yielded? Do these mutants breed? If so, is itany surprise that the first beings artificially created from our own DNAare more likely to resemble Slepian’s gurgling sphincters ratherthan mimicking the physical perfection of, say, a virtual human such asLara Croft or a mechanized being such as Gigolo Joe? Slepian succeedsin leaving us with a very unpromising vision of our biotechnological evolution,and that’s his point.

For the most part, works in LifeLike take a humorous approach to the marriage of biology and technology, deriding the sensation and hype revolving around hot topics such as genetic engineering, robotics, and the virtual vs. the real. Granted, the humor employed in such an approach may come as a comic relief to the customary gloom and doom surrounding discussion of the nature vs. culture debate. The artists might have invited a more thorough contemplation of their work, however, had they taken the topic a little more seriously, by either introducing factual evidence into their examinations or referencing social controversies relevant to our day.

Lifelike was on view June 27 - July 28, 2001 at New Langton Arts,1246 Folsom Street, San Francisco, CA 94103-3817. For more informationcontact (415) 626-5416 or www.newlangtonarts.org.