Feature: Reviews

My Top Ten, 2008

Memorable Bay Area art experiences of 2008, plus one beyond and two codas…

This list is, for good political reasons, personal. It is not drawn from every Bay Area show in 2008 — for a start, I removed from consideration art made by my San Francisco Art Institute colleagues. But it was with warm satisfaction that I realized Paul Kos’s retirement meant his exhibition West of the Great Divide: 1968-2007 (Gallery Paule Anglim, January 3 – February 2) could limbo onto the list under my ethical line. Canary/Coal (Wait for a Song) (2007) compressed pathos, sarcasm, and passion in a spare work that turned a cliché into an omen. Scything (2005), an even more economical work, magically twisted scale in a Moëbius loop of visual associations: horse/field/man/hay/(repeat with variations). Kos’s works speak of the interdependence of life and the complexities of knowing; they are works we need now.

We Interrupt Your Program curated by Marcia Tanner (Mills College Art Museum, January 16 – March 16) was also an important show, as I explained in this review. In particular, I continued to think about Maria Antelman’s video installation taH pagh taHbe (To Be or Not to Be) especially in conjunction with a related installation Antelman made for Bay Area Now 5, of which more later.

Madame 710, a video by Mary Ellen Strom and Ann Carlson in which Carlson and a cow perform a pointed homage to Joseph Beuy’s famous work with a coyote was funny, feminist, and revived the dialog Beuys started while alluding to his blind spots. Carlson screened it at a colloquium sponsored by the Interdisciplinary Program on the Environment and Resources (IPER) (Stanford University, October 23). May it return for a longer, public run in 2009.

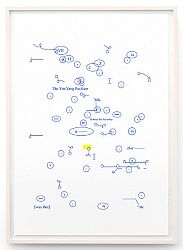

Improbable/Unlikely by David M. Stein (Eleanor Harwood Gallery, May 16 – June 28) and a presentation by Charles Gute (Catharine Clark Gallery, “Mistakes Were Made” panel discussion, October 4) also used humor to burrow into bigger questions. Stein’s Semesterville, a floating assemblage of architectural models discarded by students, was worth seeing. But the work that earned a place on this list was The Unlikely Library, a sardonic mashup of books and titles. Stein is not the first artist to do this, but he did it very well. He brought to life the alternate universe that would support such titles as Managing Thermostat Disputes and A Scientific Approach to Fringe.

Gute alters texts, too, or perhaps I should say erases them, making copy-edited page proofs into visual images by dropping out the letters. His book, Revisions and Queries, may deserve the citation but my actual Top Ten memory was of Gute drawling through a slide talk on his methods, beginning with an unpromising stammer and building to a finish that ripped a big laugh from the standing-room-only crowd. An artist who can combine philosophy and humor in a beautiful drawing, using humble carats and delete loops, has to go on my watch list.

Surprising beauty also surfaced in Radialvelic, a group show (Johansson Projects, Oakland, July 17 – August 30) featuring sculpture by Kristina Lewis, ink drawings by Jill Gallenstein, and glass installations by Kana Tanaka. Propelled primarily by Lewis’s assemblages of sewing notions, office supplies, and other humble materials, Radialvelic took “quirky” to new heights. But the accomplishment was not just Lewis’s. The gallerist has a knack for assembling group shows in which the whole is more than the sum of the parts.

Speaking of greater wholes, the combination of Ron Nagle and Don Ed Hardy (Duo Mysto, Rena Bransten Gallery, December 4 - January 10, 2009) also made for a memorable exhibition. Nagle, whose radically intimate sculptures just get better and better, showed drawings for the first time. Hardy, who describes himself as a “flat-art guy,” showed hand-painted vases along with paintings and mixed-media works. A playful video of the artists in conversation, produced by David Bransten, helped viewers become “deeply knowledgeable about art history in a non-sanctimonious way,” at least the bit of art history anchored by these two well-known artists.

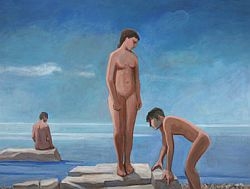

Theophilus Brown: Paintings, thoughtfully curated by Jacquelin Pilar, (Fresno Art Museum, November 21 - February 1, 2009), was a spare, focused survey of Brown’s work. With one or two exemplary works from each major period of his work, Pilar conveyed the gist of sixty-plus years in the studio. The paintings emanated strength and poise; they were a welcome break from the waning days of the Bush administration, with every morning bringing a new crash or scandal.

Everyone who invests regular time looking at art must experience serendipitous conjunctions, moments in which the order they happen to see things makes them resonate with particular force. Just such a lucky coincidence brought photographer David Maisel’s book Library of Dust, (Chronicle Books, San Francisco, 2008) into my hands around the same time I saw Liliane Lijn’s work Stardust (Riflemaker’s, London, England). Lijn’s video/sculpture resulted from a residency at Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. There she was introduced to the super-light aerogel — 99.8% empty space — used to capture space dust by NASA. Lijn projected video from her own travels into aerogel forms to fascinating effect, trapping a flickering, multi-colored ghost of the world.

Stardust seemed dematerialized, just this side of the boundary between space and substance. The objects in Maisel’s Library of Dust are just about as heavily corporeal as they could be. The “library” features copper canisters holding the cremated remains of patients with mental illness, people whose lives were lived out in a state hospital and whose bodies were unclaimed by relatives. Maisel’s photographs of the corroding canisters and their collapsing surroundings are gorgeous, lush, sensuous tributes to the dead. Together, the two “dust” bodies of work made me feel something like the words of Joni Mitchell’s song: “We are stardust, we are golden, we are billion year old carbon…”

I can’t sign off for 2008 without mentioning a show I didn’t actually see, The Wizard of Oz curated by Jens Hoffman (CCA Wattis Gallery, September 2 – December 13.) As a native Kansan, I have had an intimate acquaintance with the Wizard of Oz since the age of six. Perversely, an unexpected need to travel to my home state meant I missed the exhibition, so I had to settle for poking through the Web site. But Hoffman’s pairings of contemporary works with the novel looked magical, and even in pale, reflected digital form the exhibition suggested a fresh way of connecting visual and literary worlds.

Finally, I think it would be fair to say that in aggregate, reviews of Bay Area Now 5 (Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, Sat Jul 19 – Sun Nov 16) were lukewarm. But it gets my vote as the most-missed critical opportunity of 2008. Due to a conflict of interest, I sat on the bench as writer after writer sailed right over what I thought was the most interesting question raised by the exhibition: what can a regional survey give us, when forces of globalization mean regions are no longer so distinct from each other? Writing for the San Francisco Chronicle, Kenneth Baker did say that “The fifth edition of the YBCA’s triennial snapshot of regional art activity accords pretty well with my own sense of [the region’s art activity].” But although he referred to specific themes running through the show, he did not tackle the more general question.

Kate Eilertsen and Berin Golonu, the lead curators of the exhibition, made a significant move that deserves further discussion. Unusually for the triennial exhibition, which has always been about new work, they commissioned John Roloff, whose sculpture Deep Gradient/Suspect Terrain (1993) is sited on the Yerba Buena grounds, to create a reflexive presentation of Deep Gradient/Suspect Terrain with the history of its making. Histories, of course, are central to regional identities. Off-site works by David Buuck and Jeannene Przyblyski also recovered and told specific, and therefore local, histories. Were the curators, therefore, positing that the regional survey form can be refreshed by stretching the time covered by “now”? The very notion of a “long now,” as it is being formulated for our culture today, has Bay Area roots. We have barely begun to imagine what a “long now” might mean for contemporary art, but some intriguing possibilities broke the surface in Bay Area Now 5. May we have 2009 and beyond to explore them.