Feature: Reviews

New Work: Dave Muller and Evan Holloway

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

- San Francisco

- July 1- October 24, 2004

SFMOMA’s “New Work” series is back. The series, on hiatus since 1999, presents recently made and commissioned artworks by up-and-coming and established contemporary artists. Its return exhibition features two works by two new Los Angeles favorites.

New Work: Evan Holloway and Dave Muller occupies a small room on SFMOMA’s fifth floor, nestled within an exhibition of works from the museum’s contemporary collection. Each artist presents one work, and in theory their pairing makes perfect sense. However, while Holloway’s Map and Muller’s Sprawling succeed individually, the duo fails. The exhibition space is too cramped and yields an unbalanced, Muller-heavy showing.

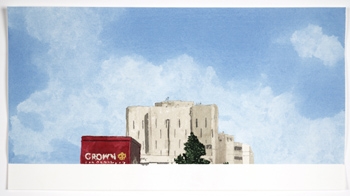

Muller presents roughly 120 poster-sized watercolor drawings, tacked in a maze-like formation around the room’s perimeter. Together, the drawings form a contiguous San Francisco skyline—but this is not a tourist’s San Francisco. It’s more idiosyncratic, and both more and less specifically “San Francisco.” Muller depicts a generic major city, complete with ubiquitous traffic lights, overflowing, graffitied dumpsters, an Alexander Calder mobile and a zoo. Helicopters and pigeons dot the sky. Locals, however, are able to situate themselves in their city through details such as a “For the Curious Ones” Exploratorium banner and “City Scavenger” stickers on the dumpster.

Muller constructs San Francisco as a floating world. This is San Francisco, but it is everyplace San Francisco—in close proximity to the Pacific Ocean, Twin Peaks, the zoo, a downtown stoplight, and the Calder mobile at SFMOMA all at once. Over half of his drawings are cobalt blue monochromes—sometimes with clouds. Initially, viewers are tempted to melt into the skyline, yielding to sensual washes and skilled, but casual renderings of the everyday. Yet despite imagery that ebbs and flows, extends and unites, the individual drawing components never become One. The scenery remains a composite, emphasized by each individual sheet of paper and the sometimes maze-like spaces in-between.

Thus, the incomplete panorama of Muller’s installation is accompanied by an ever-so-slight sense of loss. The drawings are so portable (small modules just tacked to the wall) that the action of their disassembly never quite leaves one’s mind. Muller’s renderings are tinged with inevitable displacement. Like Duchamp’s suitcase-museums and Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s untitled stacks of posters, this timely installation is suspended between continual dissemination and perpetual replenishment.

When visitors exit the museum, San Francisco will have changed ever so slightly from the time when they entered: The dumpster will be emptied. The streetlight will change from red to green. These changes will most likely be unperceivable. But things do change, and meaning shifts in time and place. San Francisco is a transient city. The twenty-somethings pictured hanging out near the Calder mobile will move to New York. The Calder is always shifting with the wind, and the Exploratorium’s banners have already been redesigned. How will such change accumulate after this exhibition is over, while Muller’s work sits in storage? How will San Francisco be changed the next time this work is installed?

Holloway’s Map (2003) is an exquisitely crafted, autonomous sculpture that strikes balance between seemingly contradictory entities such as nature and culture, color and grey-scale, art history and contemporary life. The large work mimics a Sol Lewitt minimalist sculpture, but its grid is constructed from cut, glued and painted tree branches. The work is composed of two legs that meet at a ninety-degree angle: one leg is painted in grey-scale and the other in full-spectrum color, moving from raw umbers and forest greens, to siennas and oranges, to vibrant yellows, blues, reds and pinks.

Like Muller’s drawings, Holloway’s sculpture is made up of individual segments joined together. Sections are placed in close proximity, allowing one’s perception to fill in the gaps. Ultimately, the work is as continuous as it is broken. The bent lineage suggests a timeline running from history to present day—evolving from a constructed and distilled formality to a sensual and complex realization—evocative of a jumble of colored electrical wires.

SFMOMA’s “New Work” series promises exciting new works by exciting newish-artists. While the choice of artists is to be commended, the reality of this exhibition begs constructive partnerships or solo presentations.