Feature: Essays

On the Hairy Idea of Beauty: Seven Works by Jeff Wall

- Marian Goodman Gallery

- Paris

- November 16-January 4, 2003

If the photographer Jeff Wall were a professional pool player and not an image maker, every shot would be a winning shot, making him the same rightful success in the world of pool as he is in the world of art. We might imagine that his successes in the game of pool were the result of great talent given force by set-up and surreptitious intervention: the smart hand that interrupts chance while nobody is looking in order to make a better shot, slyly nudging a ball this way or that, one helpful gesture in the reciprocity between the push and shove that characterizes the laws of physics. And, in the same manner that one reacts to the photographs by Wall, one might look upon the pool table in stupefaction, giving it the necessary double-, triple-, or even quadruple-take, all the while thinking to oneself in an oddly combined air of doubt and satisfaction, “Wait a minute, that’s not normal. That’s not right. It seems okay. But, hold it right here just a minute–it can’t be normal. It can’t be right.”

In delving into what is so “right” about the work of Jeff Wall, we begin with the notion of success. What exactly makes an image successful? In the case of Wall, it is beauty. His photographs are beautiful, and this is no accident. Making beautiful images is indeed his willful intention: “I always try to make beautiful pictures.”(in an interview with Els Barents, Transparencies New York: Rizzoli, 1987, 104.) Yet we might then query, what precisely constitutes “beauty” for Wall?

Wall’s technique in rendering beautiful images is a singular combination of modernity and tradition. In an equally willful Baudelarian fashion, Wall experiments with the latest technology while never leaving behind certain conventions of painting. While using digital technology in order to make a better photographic image - that is, “better” in the sense of more dynamic and more ambiguous - Wall often calls upon the canon of Art History in the construction of his images. In keeping with this tradition, the photographs by Wall are “works of art” in the old sense of the term. Each is fabricated with a conscientious eye toward composition. In clear reference to beaux-arts classicism, Wall balances (or imbalances) his tableaux according to a peculiarly revisionist sense of convenance. In their references to other masterpieces, his works are mimetic. The human figures of his images are, at times, brave and heroic and, at others, abject and completely impoverished. And to this array of figural positioning the viewer is empathetic. In both baroque and neo-baroque fashion, Wall uses gesture, calling on past icons of painting in the present in order to connect to the future. Yet perhaps most zealous of all is Wall’s imposition of pleasure. His images are all about visual delectation: they are meant to be seen, looked at, pondered and even enjoyed.

While with so many qualities of classical beauty, there is one notable aspect of the images by Wall that keeps them from falling into Classicism’s accompanying metaphysical abyss. Mindfully distant from that other conception of beauty, namely “beauty” conceived according to a priori perfection (that happily bygone aspect of yesterday’s Will to Power in the world of art) the beauty at work in Wall’s photography is of this world. It is a beauty based on matter, or, what I would like to discuss by way of a certain hirsute intellectual form – the hairy idea of beauty – that has been bequeathed to us, all of us, including Wall, by Conceptualism. In short, this phrase articulates an ontological shift from art as fundamentally metaphysical, its essence being beyond our worldly nature, to art as a thing created by our own hands, its “stuff” at times mysterious and unknowable, but always constructed by our own systems. This invocation of materialism with respect to Conceptualism may be understood according to several pivotal shifts in the art world occurring between roughly 1955 and 1978, that is, between Rauschenberg and, shortly thereafter, Kienholz’s first three-dimensional “assemblages” and Wall’s first large-scale pictorial photograph, The Destroyed Room. A brief but necessary digression is in order so as to elucidate the proposed “hairy idea of beauty,” especially as it relates to the work of Wall.

In the simplest terms, we may construe the increasing importance of everyday life in relation to art, its space and constitution, as part of a more general materialist turn. The shift in the late 1960s and 1970s toward physicality by way of the stuff of everyday life meant also (oddly enough) the debasement of art’s “thing”: its well-nigh transformation and dematerialization into an event, either as a lived experience or analytical thought process. Greater materialism in the definition of art, its object and beauty, meant at the same time the physical retraction of its object and beauty, in as much as the qualities of “thingness” and “the beautiful” had, up until that moment, been traditionally conceived.

The original determination of that materialism, however, lies within a very important essay by Leo Steinberg, “The Flatbed Picture Plane”. While written in 1968, Steinberg describes a shift in the art world that had been going on since the second half of the 1950s, in particular first evinced in the assemblages of Rauschenberg and, shortly thereafter, Kienholz. In the work of Rauschenberg and Kienholz (followed by the “theatricality” of the Minimalists in the early 1960s) we are witnesses to the literal fall onto the floor of the picture plane, the spilling-out and emptying of its contents into a three-dimensional space through which one could walk. It was a conceptual move if ever there were, transforming the eye into a roving body and making the work of art something one experienced in its tangible immediacy rather than by way of transcendence through rumination before painterly abstraction hung on the wall.

That the new art-in-space was inclined to immediate experience and not rumination at a distance meant not that the new art was bereft of ideas and the value of thoughtfulness. Rather, it signaled a radical transformation in the very value of the thought process constituting how one experiences art: from art, its beauty and ability to make one think – its “conceptualism” – as something characteristically transcendental to something characteristically material. The disappearance of the art object and the rise of Conceptualism, both forebears of Wall’s work, were thus part of a more general materialist evolution occurring over the last forty-five years.

In this trajectory we see the genealogy of what I have called the “hairy idea of beauty,” the conceptualist materialism and its idiosyncratic brand of beauty that is so wonderfully peculiar to Wall’s work. One rubric through which Wall arrives at this hairy, sticky, rough kind of beauty is that of realism. Focusing on the works at hand, the seven pieces that recently showed at the Marian Goodman Gallery in Paris, we see Wall wielding his penchant for, to use his terminology, “neo-realism”. (See Jean-François Chevrier, “Play, Drama, Enigma,” in the catalogue Jeff Wall Paris: Editions Jeu de Paume, 1995 14; and Jeff Wall interviewing Roy Arden, “La photographie d’art: expression parfaite du reportage,” Art Press no. 251 November, 1999, 19-20) The seven pieces at the Goodman are, while each so different from the other, in like manner neo-realist in the Wallsian sense of the term.

Resonating in the phrase “neo-realist” is a tradition of representation going back to the paintings of Millet and Courbet, the novels of Flaubert and Zola, and the lantern-slide shows of Jacob Riis of the nineteenth century. Yet following from Wall’s comments in the press release for the show, his description of the photos as “all examples of my interest of what I call ‘near documentary photography’,” we see references to a more recent moment in the tradition of realism. And here, I refer to the black-and-white shots of documentary photography, particularly the New Deal-era realism of Walker Evans, as Evans’s work is of great importance and fascination to Wall.

In the three images from the Goodman Gallery that are black and white, Logs (2002), Forest (2000) and Night (2001), Wall overtly references the realist tradition of documentary photography, using a similarly monochromatic palette but with different goals. In the tradition of documentary photography, black-and-white film was meant to convey objective reportage and not subjective art. The monochromatic palette of documentary photography signified “disinterested information,” a scenario in which the photographer became but the enabler of a machine that reproduced the truth in representation. In the instance of photojournalism as such, the photographer becomes something like a non-subject, a worker controlling a machine. What is on the opposite side of the machine is reality and between the worker and reality the machine mediates supposedly without judgement.

Contorting and confusing the otherwise seemingly causal relationship between worker, machine and reality, Wall has made three black-and-white photographs with the artistic intentions of compositional construction and, more intrinsically Wallsian, the use of hired actors. In Logs, an image of neatly cut and stacked wood, Wall has made a visual commentary on the relationship between the “natural” and the “manmade.” The image recalls another photograph by Wall, Coastal Motifs (1989), not so much in terms of form but in meaning and technique. Similar to Coastal Motifs, Logs draws our attention to the “thingification” of nature. The tidy pieces of wood in the image have been cut mechanically, making each log uniform and similar to the next. Their seriality, further juxtaposed to the mass-produced concrete blocks upon which they sit, makes the qualities “natural” and “manmade,” indeed as each adjective would seemingly describe the wood of the log and the concrete of the block, virtually interchangeable. In thingification we see not only the commodification of nature but also reciprocally the naturalization of the commodity. Far from moralizing to us about the interminable reaches of capitalism, Wall describes matter-of-factly that just as much as nature has become a commodity, the commodity has become natural to us.

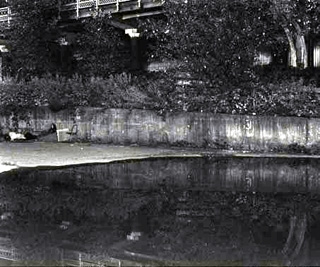

This type of ambiguity is essential to Wall’s photography, and we see it at work in both Forest and Night. Very much in the vein of Depression-era documentary photography, these two black-and-white images include human figures. Forest is an image of a solitary women in wintertime, seen obscurely through leafless trees walking away from a meal of eggs and sundry found foods being cooked on a small makeshift fire. We assume that she is homeless and that the image is an example of photojournalism, the message being conveyed one of a classically noblesse-oblige tenor, “we must do something about poverty.” Economic destitution is similarly thematic in the photograph Night. The landscape of Night is however more explicitly urban than Forest, depicting a culvert beneath an embankment over which runs train tracks or a roadway. A small group of people, one would assume homeless, occupy the left side of the composition. The two images prima facie seem very aestheticized, precisely in the pot-shot pejorative sense of the term, as though Wall were making art out of poverty. But, they are aestheticized images and Wall has the right to aestheticize these figures because they are not homeless people. And this is precisely Wall’s point. Reality is not what it always seems, and this should be the lesson, perhaps counter-intuitively, perhaps in hindsight, that documentary photography has left to us. Through the referential game with documentary photography Wall tells us that there can never be a disinterested image or a disinterested image-maker. Moreover, “reality” itself is so labile that it is deceptive to claim it ever to be rendered static or captured (or capturable), in a photographic image. In a pattern of inversion and reversal similar to that of Logs, the girl in Forest and the people in Night represent what they are not. In reality they are actors hired by Wall to play a role in a highly staged photograph. The figures represent at once what they are and what they are not, or to use Wall’s terminology, their identities and non-identities, selves and non-selves.

The four color photographs of the show, Cuttings (2001), Rainfilled Suitcase (2001), Overpass (2001), and Dawn (2001), are similar to the black-and-white images in that, while they are rather varied in nature, each one different from the other, they hold in common a sense of realism. They are images so recognizable in their banality. As leftover fragments, the detritus of everyday life, the only thing keeping us from completely overlooking them is Wall’s extraordinary treatment of them, his choreography of figures, technical intervention and gross enlargement. Yet, because they are color, cibachrome images, their “realism” carries a different meaning from the monochromatic images discussed above. Rather than referencing the more recent lineage of twentieth-century documentary photography, these color images draw our attention to the long-standing canonical pictures from the history of painting.

The first two images, Cuttings and Rainfilled Suitcase, are smaller in scale than the other color photos, bringing to mind the tradition of still life painting. This is especially the case with Cuttings. Cuttings is reminiscent of an earlier photo by Wall, Bad Goods (1984), a pyramidal composition of, in the top-most corner, a North American Indian, in the near-bottom right corner, a small heap of rotting lettuce, and the third left corner, outside of the picture plane, the viewer herself looking onto and inside of the picture plane. The heap of lettuce heads constitutes something of a still life of vegetables, not unlike each of the three bundles of wood in Cuttings. However, with the figure of the Indian in the upper part of the tableau of Bad Goods, the image immediately becomes a social commentary. In Cuttings there are no people and thus seemingly no social commentary. It is just an image of la nature morte. Or is it? In this turn of phrase, la nature morte, the French term for still life, we might begin to think once again of the ambiguous play between the natural and manmade that is important to the image Logs, as Wall references a similar type of dialectic here. And thus Wall has depicted in this still life of kindling “dead nature” in the truest, most ambivalent sense of the term.

The image Rainfilled Suitcase is slightly smaller that Cuttings, thus bringing to mind the early modern marketplace of painting that flourished during the seventeenth-century in the Netherlands. During this time, the “Golden Age” in Dutch art historical parlance, there was an efflorescence of painting the scale of which, not unlike Rainfilled Suitcase, would be appropriate for the interior of the home. While Rainfilled Suitcase may reference in its scale an early market place for bourgeois interior decoration, it signifies its opposite by way of its contents. A wonderful example of Wallsian dynamism and ambiguity, this image of an open suitcase with its contents spilled scattershot on the ground references identity and non-identity, self and non-self through the ambivalent to-and-fro that occurs between interior and exterior, life at home and nomadism in the street.

The two final color images, Overpass and Dawn, are enormous in scale by comparison. Both images are set within rather nondescript urban landscapes, those that characterize the city from which Wall hails, Vancouver, British Columbia. In its size and composition, Overpass clearly references painting in the grand style of the nineteenth century. It is an image of four figures walking away from the viewer. They face us with their backs. They are walking over a bridge, an overpass, in what one might describe as a “post-industrial landscape,” where in the distance the grill and front of a semi-truck, the symbol par excellence of this type of meta-urban setting, is discernable. In composition, the figures walking over a bridge reference the urban Impressionism of Caillebotte. And, the amazingly daunting pall of heavy blue that covers the sky above brings to mind those skies so particular to the Dutch landscape, with its wet geography and mercurial weather, and its tradition of landscape painting of the seventeenth century.

Dawn, while not as forcefully referencing iconic images from painting’s glorious past, is like Overpass, large and urban. There are no people, just lines of sight and composition inscribed by electric wires and utility poles, its composition recalling the rather Malevitchian formalism of an earlier image by Wall, Diagonal Composition (1993). Slightly off center, adjacent to the incline of the street in the forefront and contrapuntal to a spray painted dumpster to the right, there sits a rock. This rock, coupled with the soft light of dawn, creates a mood of calm, zen in the city before it is astir with work-a-day business. In fact, we might take this cast-aside corner of residual space in the city to be just that: a post-industrial zen rock garden.

While the canonical referencing in these final two images renders them vibrant with wonder and accessibility, what makes them so present in the world today is their urbanism. Wall’s urban perspicacity is, I would argue, one of the most consistently powerful qualities of his images. The influences of Baudelaire and Benjamin in Wall’s thinking, especially their singular brand of urban investigation, are evident through his frequent citation of them in conversations and interviews. One might look to Wall’s extraordinary Landscape Manual (1970), a series of snapshots of Vancouver’s perverse urbanism with typewritten commentary bound in conceptualist-cum-catalogue fashion, for an earlier version of such Baudelarian visual flânerie. Yet, where the notions of “flânerie” and the “painter of modern life” reveal themselves most clearly and powerfully are in Wall’s ability to render photographically the urban periphery in all of its utopian potential. In altogether Benjaminian fashion, Wall brings the dialectic of seeing to the urban periphery, to landscapes of sprawl and to the back lots of run-down, low-level, lowbrow, struggling-to-hang-on, three-job-holding middle class life. There we see in the embers of ugliness, that is, the proverbial faux fireplace of the suburban interior and decentralization’s thoughtless warehousing, beauty’s flickering light. In the dialectics of seeing, Wall allows us to see in the plain body of urban sprawl its non-identity, what it is not through what it is, that is to say, a landscape so profoundly beautiful and endlessly interesting.