Feature: Reviews

Philip Guston Made Me Do It

- SFMOMA

- June 28 - September 28, 2003

Pick a painting from across the room. Go up and look at it. It’s the same painting, only closer. Any new information is just evidence of what you already knew. Let’s say it’s a mound of giant cherries. The more you look, the more you realize: cherries. A whole pile of them. Each dab of paint, every brushstroke, all going toward making the painting look like cherries.

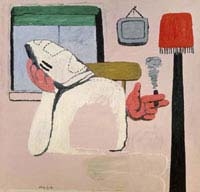

Another painting has hairy feet, trashcan lids. A clock. You could ask what it means but you might walk right past Door Number One. It’s not hard to see the world as a series of combinations of nouns. After all, most things are completely still most of the day. Yesterday on the street I saw, in combination, a doll torso, a dented colander, a dirty rabbit’s foot key chain. This next painting’s got cigarette butts and pointing fingers, a hairy spider. Everything out of action, frozen right there in front of you. Maybe it means: This is a painting I made of cigarette butts and pointing fingers.

The story of Philip Guston always pivots on his dramatic transition from heady abstraction to comic-like figurative painting. Back when I studied art history, I thought the switch was important for loosening the necktie of abstraction and forcing us to re-think the state of painting. It seemed like courageous, shrewd commentary. But now I don’t think you can paint that pile of cherries and think too much about anything but cherries. I’m just not convinced the switch was as conscious as the history books say. Guston made his sardonic Nixon drawings (on view at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco last winter) early in the pivot, and looking at them in person I got the feeling he was simply trading in his abstract expressionist tools for less ambiguous ones to get across his seething frustration about Vietnam and the government-abstraction just wasn’t doing the job.

Guston was dedicated to his paintings outside of their reception, but he wasn’t simply lost in the world of his studio, an unattended falling tree with nothing more to say than Doesn’t this pink work surprisingly well against this gray? He had a notoriously hungry mind for poetry, philosophy and art history. But he was a painter first, and expressing himself personally and commenting on the state of painting are two different things. The first is much richer territory, and I think, his primary concern.

There really is such a thing as being compelled to paint, and Guston’s paintings embody that need more than any artist who comes to mind. Now that I paint every day, I feel more and more skeptical of the conscious meaning artists (and critics) place on their work - in Guston’s case, I imagine his best paintings came when he cleared his mind of all that consideration and thought, I need a clock in this corner. Now. Or, Nixon’s cheeks look like testicles.

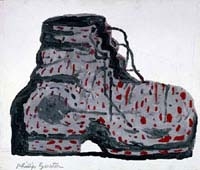

Not that the abstract paintings aren’ similarly fueled by immediate, visceral decisions. That was the central missive of the abstract expressionists, of whom Guston was a star member. Simply put, I think his pivot was merely stylistic. Everything of substance you see in the figurative paintings you can find in the abstract ones. The brushstrokes, the line, even the exact colors are all there. In retrospect the abstract paintings appear to be crumbled or melted ruins of the figurative ones, the rubble of great monuments to significant ladders and giant shoes.

The current Philip Guston retrospective at SFMOMA is a fine place to see many paintings from across the years. As a well-behaved retrospective should, this one presents the paintings in chronological order so we can see how he got from here to there to there. It’s a suggested road map for explaining the transitions and showing the development of his painting so we can get a clearer sense of what he was trying to say. But it’s the stress on this kind of detective work that pushed me out of academia for good. Even mainstream novels and movies have been juggling and splicing time as a way of engaging the viewer for decades now… why does the study of art still rely so heavily on the timeline? Linear connoisseurship is the obvious route, but Guston’s paintings demand something else altogether… what made him paint like this? What do they say to us? What makes us walk up to one and stay there well after we recognize it as a bare lightbulb or an abstraction of reds and pinks with some black and green mixed in?

Using chronology as a guide you can easily forget to look for more than the next stepping stone. You walk right out the door confident you understand the plot without ever being confronted by any of the complex, enigmatic characters. It’s too easy to walk past a painting of a giant wheel and think this was made at the height of his Wheel Phase.

Look at two of the big paintings in the show as just two big paintings in the show. Sleeping is an oversize oil painting that’s grumpy, adorable and despondent all at once. A lone older man is folded up in a too-small bed with his shoes on, cold and consumed with sleep. His hair is everywhere. His fingers, earlobe and eye lashes all hang over the lip of the blanket. He’s a mess but he’ll survive. The background is black as nothing. This isn’t commentary on painting - it’s commentary on living in the world. It’s a scary place but we all get through it somehow.

Now look at For M, also big, with a similar palette but this time less black, more skin tone. And abstract. It’s a loosely arranged cluster of brushstrokes, collected in a pile like the remains left on a butcher’s block. We know it was painted - you can easily see the brush - but the composition is unlike most human creativity: no pattern, no recognizable form, unlike even a quick sketch in the dirt. As a viewer you know it’s man made but you’re not sure why. Like that unknowable line between tears of joy and sorrow, you can’t even tell if Guston’s happy or incensed, just that he feels it very deeply.

I don’ wonder how Guston got from one painting to the other. I wonder how he managed to isolate the intensity of emotions without assigning them. You know he was emotionally charged, and his biography confirms it (for example, at age ten he found his father post-suicide). But you can’t be sure in which direction he felt the fervor. A big lone boot is funny and pathetic and somehow just sitting there too. The despondent Klansman smokes a cigarette, hateful, but clearly harmless. (Can you imagine satirizing the Klan in the midst of the civil rights movement? Talk about testicles.) Without the map, you have to wade through the murky waters of all of these emotions at once, and acknowledge that it was a simple abstract ink drawing that brought you there. It’s an entirely humanizing experience.

In the end, mixing up the stepping stones helps to diminish the how he got here question and spotlights the what is he trying to say one. In Guston’s case, it’s all there in the painting: the smarts, the joys, the pains and all the motionless nouns. And most importantly, the questions. As he once put it, “There’s some mysterious process at work here, which I don’t even want to understand.”