Feature: Reviews

Sophie Calle: Public Spaces - Private Places

- The Jewish Museum

- San Francisco

- March 7 - June 28, 2001

Growing up, my hero was Phil Donahue. I was fascinated by the social/political nature of his shows, the personal interview format and his ability to bring highly controversial and often taboo subjects such as transvestites and incest to the mainstream public. In essence, the same could be said of French artist Sophie Calle whose performative work is the highbrow version of the talk show tabloid mixed with a dose of Candid Camera. Calle herself often alternates between probing host and vulnerable, tell-all guest/subject.

For over 20 years she’s toyed with the lines between public and private as voyeur and provocateur, testing these limits long before ‘reality shows’ such as Big Brother, The Mole and Survivor were ever a possibility. Calle’s most notorious and naughty work has included the stalking and photo-documentation of strangers, who became the unsuspecting subjects of her obsessive ritual.

The captured moments were later displayed with Calle’s collected observations as a photo-text installation. In a similar piece performed in 1983, Calle found an address book on the street. She returned it, but not before calling each of the phone numbers listed to gather information on the book’s owner. She then published their perceptions of him in the French newspaper, Liberation. Such disturbing and impish acts have rightfully earned Calle the title of ‘Bad Girl’ in the art world. However, as surveillance and shock have become commonplace, Calle has both matured and raised the ante in her recent work.

Her exhibit, Public Spaces - Private Places at the Jewish Museum explores the boundaries of space in Jerusalem, a city bitterly divided by claims to its sovereignty. In this investigation, Calle considers the metaphoric borders created through the Orthodox Jewish tradition of erecting an eruv.

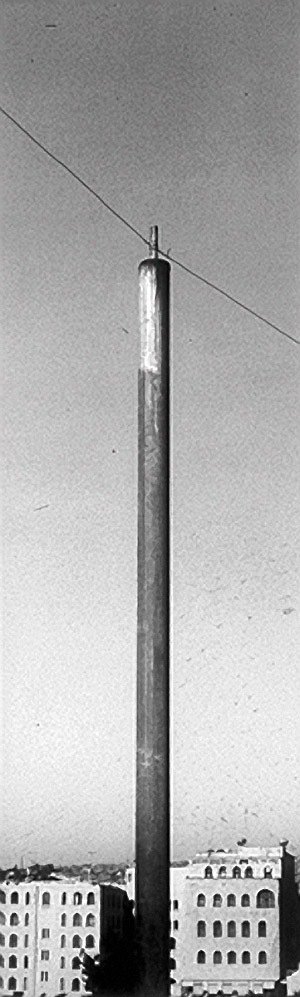

The eruv is a physical and symbolic enclosure created by stringing galvanized steel wire from poles in and around a Jewish community. This practice is used as a way of stretching the Talmudic law that prohibits the transfer of objects outside of the home on Sabbath (every Friday at sun down until the following day at sun down) by defining the space within the eruv as “home.” The ritual of honoring the eruv is quite involved and in Jerusalem it includes a weekly assessment by an “eruv inspector” to insure that the lines have not been damaged. If any gaps are spotted, the repairs must be completed before the beginning of Sabbath, otherwise an announcement is made by rabbis throughout the city that the space is not protected.

Twenty panels of black and white photographs of Jerusalem’s eruv line the walls of the gallery, symbolically recreating the sacrosanct space. Calle also asked fourteen residents of the city, both Israeli and Palestinian, to take her to public places they consider private and share their personal associations with the sites. Their stories are documented anonymously through framed 4x6 photos and text (one 8 _ x 11 sheet each) that have been placed atop a map of Jerusalem in the center of the gallery. Due to their size it is unclear if Calle was attempting to connect the stories and images with their actual geographic placement on the chart, though it seems likely. The narratives reflect the complexities and contradictions that accompany the notions of territory and “other,” as well as reveal the seemingly banal, yet ineffable memories experienced by everyone:

At first I was attracted by the bucolic appearance of the olive groves and terraced landscapes; the contrast between the pastoral images, full of gentleness that might have inspired Poussin, and the harsh, political, tribal reality;

There is nothing specific, nothing particular about that spot; just an accumulation of experiences and memories. This is where you learn, in the street, that’s how you’re shaped.

The most powerful and provocative impression was left by Calle’s contextual frame for these personal images, and specifically the memories of Palestinians presented within the heavy and profound symbolic borders of the Jewish eruv. I could feel my own edges being pushed by this choice of position and the subtle betrayal implied. Yet this is the strength of Calle’s work—her ability to evoke and challenge our innermost limits of human experience and behavior, surreptitiously invading and helping to redefine our own internal spaces.

Also on view at the Museum are several pieces from Calle’s earlier pursuits: The Sleepers, 1979, for which she invited 29 guests to sleep in her bed while she photographed them; The Blind, 1986, documentation of interviews conducted with people who were born blind and asked to share their images of beauty; and The Autobiographical Stories, an ongoing series of photographs paired with text that overtly focus on the artist as subject. These selections help to give viewers unfamiliar with Calle an introduction to her prior work. However, as segments of larger projects they lose some of the intrigue and poignancy generated by her complete installations, such as The Eruv.

Sophie Calle: Public Spaces - Private Places

The Jewish Museum

March 7 - June 28, 2001

121 Steuart Street (between Mission and Howard Streets), San Francisco

Sun. - Thurs. 12p.m. - 5p.m. (415) 591-8801