br>By Mary Anne Kluth Melancholia (1514), Albrecht Dürer; engraving; plate: 9 3/8 x 7 5/16 in.; sheet: 10 x 7 15/16 in.; Estate of J. K. Moffitt.

Untitled (1988) Louise Bourgeois; watercolor and pencil on paper; 11 in. x 9 in.; gift of the artist and Jerry Gorovoy.

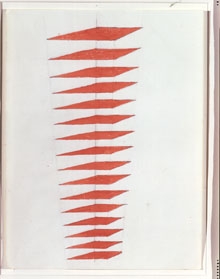

Golden and Silver Ever Lasting Spiral (1995), Acharya Vyakul; mixed media on paper; 6 3/4 x 9 5/8 in.; purchase made possible by a gift from John Bransten.

Feature: Essays

The Berkeley Kunstkammer

The Berkeley Art Museum, mimicking the behavior of past princes and early capitalists, is eager to impress visitors with its significance as an entity of wealth and prestige. Using works collected by both the museum and the university, the Kunstkammer exhibit uses Renaissance-era strategies in an attempt to create an identity for the museum as a wealthy and powerful entity in the art world.

Sixteenth century Kunstkammern and Wunderkammern were private exhibits created by individuals with the financial and logistical means to amass collections of art and natural or technological artifacts. Often pieces intended for such collections were exchanged between collectors as gifts, and functioned as political currency. These collections were arranged, often in specially built rooms, with the intended effect of dazzling visitors by, first and foremost, the sheer encyclopedic array of objects collected. The second intention of these collections was to symbolically represent a microcosm of the universe. This is done by sequencing and grouping objects according to formal attributes, as opposed to art historical qualities, and allowing these formal attributes to amass into a symbolic lexicon that articulated a hierarchical view of the universe through “correspondences” between the pieces on display and facets of the natural and political world. The collector then simply positioned symbols referring to him or herself in powerful or prestigious relationships within the collection, and thus a similar identity was articulated. A typical example of this kind of Kunstkammer is the collection of Habsburg Emperor Rudolph II, who ruled from 1576 to 1612.

The Kunstkammer exhibit self-consciously imitates this activity, though the show substitutes the art world for the natural and political world. The wall text at the beginning of the show makes this imitation clear, starting with the title. It then relates a brief history of the Berkeley Art Museum, characterizing it as an institution aiming to display works from a range of art historical periods for the edification of the “university community.”

It boasts that this specific exhibit spans “400 years and multiple continents,” though it admits that the exhibition consists mostly of works on paper, while actual Kunstkammern often combined works of art with “scientific apparatus and products of nature.” But ultimately, the display is characterized as “reminiscent” of a Kunstkammer, not as imitating one. This affords the curator(s) space to list famous and glamorous artists included in the exhibition in a printed handout: “Albrecht Dürer, Louise Bourgeois, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Paul Gauguin” without breaking form from traditional Kunstkammern, which did not attribute works to artists in writing of any kind .

It also directs attention toward the similarities and dissimilarities between styles of arrangement of the works in the exhibit and in Kunstkammern, and away from the possibly more substantial symbolic work both old displays and this one are doing. Possibly the most Kunstkammern-like facet of the display is the way it constructs a miniature symbol system representing the real world, and uses it to assert the status, power, and prestige of the museum. This activity is ignored in the wall text because such constructed self-representations rely on erroneous conflations between the microcosm and the macrocosm, or the model of the world and the actual world, and to direct attention to these substitutions is to risk revealing their faulty logic.

One wall of the exhibition in particular does a large share of this covert identity-construction through the use of a model. The final wall, positioned opposite to the wall text, could function as a miniature exhibit of its own. It contains the widest formal array of artifacts simply because it includes the only sculpture. Lyrically arranged to create a balanced overall composition, two etchings, five photographs, four drawings, a drypoint print, and three small sculpture vitrines hang from the wall at various heights. Formal resonance ricochets across the arrangement.

The two large photographs in the center, Elizabeth Demaray’s Half, all the apples on one tree in an orchard, halved, a photo aptly described by its title, and Richard Misrach’s 10-14-00 from the “Golden Gate Series,” a silvery view of the Golden Gate Bridge in fog, set a master theme like a pair of conductors directing a visual orchestra, and the surrounding, smaller pieces respond to their visual cues. In the center of Demaray’s photo, two apples hang from a branch, sliced perfectly in half to reveal the white flesh ringed with red skin, black seeds dotting their centers. This concentric arrangement of color value is echoed immediately by Paul Klee’s Neigung der Blüten (Blossoms Bending), a loose, landscape-format drawing consisting mainly of one frenetic line tracing connected spirals across the blank page.

This same type of spiral is isolated and carefully rendered in the blue and silver colored Golden and Silver Ever Lasting Spiral, a small mixed media work by Acharya Vyakul. From there the formal echo splits, and two pieces ring in response. The first is the large Misrach work, which has the same allover metallic, silvery sheen as one of the two drawn or painted lines in the Vyakul. The second is Color Study Candy Bibles, by Kyungmi Shin, which features two huge candies, cast in the size and shape of a parishioner’s hand-bible, one cream colored, and the other a turquoise that repeats a lighter shade of Vyakul’s blue.

A viewer looking for thematic connections can match the bibles with the apples from the initial photo, common symbols for the fruit of knowledge in the biblical Garden of Eden. And the material the bibles are cast in, “sugar,” is literally written, along with the formula “H20,“on the Jean-Michel Basquiat drawing “Untitled (New York City). And it is the surface of water, not its chemical make-up, that is the only subject of the small but famous Vija Celmins Drypoint – Ocean Surface, which hangs just below the large Misrach photo.

Though comparisons can branch any number of ways among the pieces on this wall, depending on the attention of the viewer, quickly a web of similarities in subject matter grows. Plant life, like that in the apple photo, figures in Federigo Barroccio’s 16th or 17th century etching, Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata, Marion Brenner’s photo Sunflower, Joel Meyerowitz’s photo Cape Canaveral Moon Launch, a photo of a couple and a car in a dark glade of trees, and Constance Chang’s small drawing, Landscape in the Style of Huang Pin-hung, which sparely depicts a man and a tree in front of a mountain. Eva Hesse’s Test Pieces, small half-domed, silver colored sculptures with the surface texture of seed pods, look like they could have grown from a tree, albeit a metallic one, at one point.

People figure in many of the aforementioned works. Combining with the water and plant imagery, a poetic sense of the world begins to coalesce. People exist in a world of plants and water, the arrangement implies. As if to confirm this interpretation, Johann Georg Bergmuller’s 18th century etching of Sainte Anna hangs in the top left-hand position, depicting a woman on a cloud. Such an image positioned in the corner of an arrangement of vegetation, people and water recalls the anthropomorphized North Wind on cliché Renaissance maps of the world. This map imagery makes metaphorical sense with the Bibles and biblical imagery, which obliquely reference any religion’s goal of defining humanity’s moral place in the universe.

Confirming that the arrangement represents a map or microcosmic visual model in the tradition of the Kunstkammern, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Untitled sculpture sits like a map legend beneath Sainte Anna. Consisting of the words “feu,”“air,”“terra,“and “water” typewritten on tiny rectangles of paper and strung on a thread inside a small glass jar, it is a miniature model itself, housing a tiny paper representation of the complete set of Aristotelian natural elements, in a similar manner to the arrangement containing the sculpture or the museum housing the whole display. With a spiral of representations, the museum has located itself in the universe, and the universe within itself.

Of course, the Berkeley Art Museum couldn’t possibly contain a collection so encyclopedic as to make this constructed identity a fitting representation. But the Kunstkammer exhibition strayed from the example of historical collections and published a list of the works included in the show, ostensibly so viewers can verify that works did indeed come from all over the world and span many centuries. Another purpose of this listing is to reinforce and clarify the location of the museum in the model that has been constructed in the exhibit. The museum is not intended to seem like it has possession of the whole world in miniature, it only lays claim to a miniature art world, and the implications of that collection. The listing reads like a pedigree of institutionally lauded Western art. Just in this exhibition alone the museum boasts two Dürer prints, two Picasso prints, a Miro, works by local art heroes David Ireland and Raymond Saunders, a Motherwell, a Bourgeois, a Toulouse-Lautrec, a Gauguin, a Marden, a Daumier, an Erwitt, a Derain, a Courbet, a Dine, an Albers, a Bontecou, a Roberto Matta, as well as the Adams, Hesse, Celmins, Klee, and Basquiat on the final wall.

Also listed is the provenance of each piece. Of the 95 works on exhibit, a full 73 are listed as gifts of museum patrons . Of course patrons donate partially in order to receive this public recognition, but another implicit meaning is that museum not only has an impressive survey of modern art, but also that this art was gotten through a supportive community wealthy enough to donate expensive objects valued by other art world institutions.

The only factor mitigating this grand statement of art world significance is the actual exhibition itself. Leaving judgments of beauty and general quality aside, the works, except for the three small sculptures on the last wall, are all works on paper, many of which are editioned prints. Traditionally, this is the genre of work with the least market value that a collector can purchase before one stoops to buying reproductions. The value implied by the listed artists and the value assessed in the actual exhibition are not identical. Many of the listed artists, Picasso for example, are known largely as painters, and a reader not paying attention to the fine print on the listing could be disappointed to find some of his lesser-known print work hanging in the show.

After the initial bedazzling effect of so many works crammed into such a small space, it become apparent that many of the pieces are souvenir-like and small. The exhibition alludes to this quality with the inclusion of an undated Tom Marioni piece titled John Cage’s Autograph which appears to be just that, scrawled quite legibly on a torn corner of water-marked paper. Perhaps the inclusion of this autograph can be seen as an institution admitting that some parts of the exhibition, and by extension the entire museum collection, are included not so much on account of their formal excellence, but as a part of a list-like pedigree that qualifies the museum to command support and recognition in the art world. Or perhaps this autograph has not one but two famous names attached to it, and so can be counted twice as a trophy and “object of wonder.” Or perhaps it functions both ways.

1. Berkeley Art Museum. “Works in the Kunstkammer,” Printed exhibition handout. Berkeley, CA: 17 Apr. 2007 through 14 Oct. 2007

2. Dennis, Sarah. Lecture. HA N186C. Berkeley, CA : University of California, Berkeley. 4 Jul. 2007.

3. Kaufmann, T.D.. “Remarks on the Collection of Rudolph II: The Kunstkammer as a Form of Representatio.” Grasping the World: The Idea of the Museum. Ed. D. Preziosi et al. VT: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2004. Pp. 527.

4. Ibid pp 532.

5. Ibid pp. 526, 530.

6. Cannizzo, Stephanie. “Kunstkammer.” Exhibition wall text. Berkeley Museum of Art. Berkeley, CA: 17 Apr. 2007 through 14 Oct. 2007.

7. Dennis, Sarah. Lecture. HA N186C. Berkeley, CA : University of California, Berkeley. 4 Jul. 2007.

8. Berkeley Art Museum. “Works in the Kunstkammer.” Printed exhibition handout. Berkeley, CA: 17 Apr. 2007 through 14 Oct. 2007

9. ibid

10. Cannizzo, Stephanie. “Kunstkammer,” Exhibition wall text. Berkeley Museum of Art. Berkeley, CA: 17 Apr. 2007 through 14 Oct. 2007.

My Great Great Aunt Pauli Hirschal who was also my dear friend along with Frieda and

Anna Marie Nadolny live in our hearts through their gifts to Bay Area art.

Thank you Mary Anne Kluth for this article. My love is still deep for these ladies.

Mark L. Jones • October 05, 2011