Feature: Reviews

The Sixth Sharjah Biennal

- Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

- April 8-May 8, 2003

Through the Arabic Window: Evidence of Human Values

The Sixth Sharjah International Art Biennial took place from April 8-May 8, 2003, in the southern extremities of the Persian Gulf, Sharjah, in the United Arab Emirates. For all the cultural visitors convening in Sharjah, the surreal reality-TV-show war between the USA/UK and Iraq (widely felt throughout the world to be unnecessary, unpopular and illegal) reverberated in the psyche with a strange urgency. Yet a sense that art and culture may act as a counterbalance to warfare and cultural ignorance reigned supreme.

Sharjah, one of the seven Emirates comprising the United Arab Emirates, is a port city like Venice, sharing numerous large ocean-going lagoons that feed into the Persian Gulf. It is also an open zone for a wide-ranging intellectual and artistic meeting unparalleled in the region, if not the world, at this moment. Sharjah’s tolerance and support of artistic and intellectual productions is a testament to the far-thinking ideas of the royal family and two men: Sharjah’s leader His Highness Dr. Sheikh Sultan bin Mohammed Al Qassimi, and a Department of Culture attaché,Essam bin Saqr Al-Qasimi. They have invested much capital in cultural assets and programming. The charge of building intellectual and artistic bridges to the Western world reverberates between Cairo, Beirut and Sharjah, energizing a new space of tolerance between the colliding cultures of East and West.

For the people of Sharjah who had planned for this Sixth Biennial, enormous change was in the wind. A fundamental shift in curatorial mission occurred, under the leadership of Sheikha Hoor Al Qasimi and staffers Hisham Al Madhloum and Talal Moualla, who deviated from repeating the past model that featured mostly regional and international art practicioners in the schools of painting, drawing, sculpture and photography. Instead, they engaged newer Western art modalities of video, installation, performance art.

One positive outcome of earlier Sharjah Biennials was that they served to closely knit the Persian Gulf artistic community by providing an international forum and gathering for developing artists from Oman, UAE, Bahrain, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait with larger neighbors such as China, India, Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, and Taiwan. Numerous European and Asian artists have participated since the Biennial’s founding in 1991, but the curators have taken care that their numbers are not so great as to outflank regional artists in this fragile, formative stage of their development. Gulf artists shared work and passed on new ideas, styles and techniques in rapid fashion without being overwhelmed/usurped by the prevailing and powerful Western art world.

In the UAE and the rest of the Arab World the ghosts of colonialism continue to plague and traumatize. Little facts: 1) the U.K. administered the Trucial Emirates from 1821-1970’s and never built a single school building 2) the ongoing American military invasion, occupation and colonization of Iraq creates a burning chaotic hole in center of the Arab World. These circumstances breed mistrust of Western intentions while a world away the American popular media engulfs its citizens with anti-Arab diatribes, finding no positive attributes in Arabic/Islamic Culture. So Arabic artistic identity has had to continually struggle with or against these forces and preconditions; but now Arabic artists are challenging neo-colonial globalism with the tools of postmodern art, creating an exacting and visceral vision in and of the Arab world in the troubled, polarized and violent 21st Century. Preserving and promoting the concrete human values inherent in the Islamic world seemed the larger aim and theme of the artistic endeavor, along with sharing this positive, galvanizing identity with the larger world.

Curators Sheikha Hoor AL Qasimi (UAE) and Peter Lewis (UK) collaborated with a number of international curators such as Britta Schmitz (Germany). After picking over numerous ideas, themes, artists and bits of advice, they invited 117 artists from 25 countries to show a wide range of works in the Biennial’s principal art venues such as the Expo Center and the Sharjah Art Museum. For the Arabic/Islamic artist, the Sharjah Biennial offers a chance to slip out into the greater art world and achieve more notice and critical acclaim as European curators and art institutions have begun to focus on this underserved group of artists. International exhibitions such as 5/UAE in Aachen, Germany, at the Ludwig Forum for International Art and DisORIENTation at the Haus der Kulteren der Welt in Berlin have featured numerous installations, videos, and photography from emerging Arabic artists exploring difficult issues of personal history and identity. One of the ten curatorial sections of the 2003 Venice Biennial featured Arabic artists from Lebanon and Egypt. Other traveling shows are Contemporary Arab Representations: Beirut/Lebanon at BildMuseet, Umea, Sweden and Contemporary Art Representations, Cairo at the Witte de With, Rotterdam, Netherlands. These exhibitions are helping to illuminate the work of Arab/Islamic artists as they increase exponentially in numbers and influence.

The exhibition opened with ubiquitous images of Mohammed Khazen: street posters, a 24 hour DVD projection in front of a convention center, and advertisements on television. These large and ever-present images, self-portraits, grew to mythical/symbolic proportions. In them, Khazen portrayed himself, back to the viewer, as representative of the Arabic modern artist. He is posed as if surveying the growing urban center of Sharjah from a distant vanishing point in the desert. One sensed the formality and seriousness inherent in this radical self-definition of the Arab artist. The frangible desert becomes a stage for his heroic, strenuous efforts to determine a kernel of memory amid an urban culture mushrooming on all sides. Khazen offers a sense of frank introspection in the face of the large-scale and indifferent forces arrayed against man—a theme that obsessed the American writers Joseph Conrad and Stephan Crane.

Khalil Abdulwahed Abdulrahman (UAE), one of the exceptional finds of the Sixth Sharjah Biennial, offered a taut, well-edited digital video, with mesmerizing color shards exploding into a seeming endless time frame. It offered a glimpse of eternity close-up, as a mystical and succinct visceral experience. Seifollah Samadian (Iran), an experienced photo-journalist and cameraman for the cinematographers emergent in Iran in the last twenty years, showed his enigmatic and brooding still shots in varied formats, and two recent digital videos, White Station (which was like watching a silent Chekhov short-story) and The Art of Killing. Runa Halawani (Palestine), gave eye witness to brutal military oppression in large format, striking negatives of the Israeli occupation of the Palestinian Territories, such as a well-dressed man splayed on the street in a pool of his blood with a menacing tank in the distance. The affect was reminiscent of Goya’s The Third of May 1808 (1814). One would like to see them hung in proximity. Rana Al Khamiri (Bahrain) focused on polluted regions in her country, where the fragile tidal watershed is trashed with the detritus of modern culture. Her compositions were made with odd, refreshing angles; they worked both as documentary images and esthetic explorations.

Zineb Sedira (Algeria) offered luminous, large, color self-portraits of herself wearing a white jalabah, to elegant and hermetic effect. Munira Aljalahma (Bahrain) used local earth and floral materials transformed into useful objects or massed in arresting shapes. In a series inspired by a tile mosaic from the Umayyad Dynasty (8th century), Sharif Waked (Palestine), in Jericho First, depicted a lion devouring a gazelle in a series of uniform panel canvases with the images progressively reduced: Israel gobbling Palestinian land? Taraneh Hemami (Iran) collected fragments of personal letters and photographs, which she superimposed in square artifacts, making a dazzling array of transparency and layered memory. Full of Persian script and design motifs, like votives displayed among piles of rubble, these objects suggested the way violence atomizes identity and self-history. Wejdan Salem Almannai (Bahrain) offered pure/rarified aesthetics, using unprimed canvases marked by neat concentrations of pins or running colors. Muted shapes emerged with dramatic intensity yet with a formally beatific quality. Zain Mustafa (Pakistan) collected native garments (kurtas) and stitched them together in looping lines of frayed white clothing covered in graffiti-like anti-war messages from the USA. These ghostly, dangling shrouds were fiber art in the service of anti-war frustration.

Bakr Sheikoon’s (Saudi Arabia) absurdist upside-down installation in a stairwell, The Vent Chamber (2003) seemed to match the political undertow of simmering resistance toward the Arab stereotype. Al Fadhil (Iraq) offered large black and white photographs from videotapes of blindfolded men surrounded by Saddam Hussein’s soldiers. Kai Wiedenhofer (Germany), who has been working as a journalist in the occupied Palestinian territories since the 1990s, captured Bresson-like, incisive black and white images of the occupied Palestinian territories. Tarek Al Ghoussein (Palestine), another possible art-star, offered a brilliant series of large digital color prints portraying himself as a roving target and provocateur. Shadi Ghadirian (Iran) made color large-scale photographic portraits of Iranian women covered in chadors of interesting fabrics with the face hole covered/blocked by kitchen implements such as large rusty frying pan, avocado green Teflon bowl, a colander and a shimmering new butcher’s knife—exceptional work. Faisal Abdu Allah (UK) showed large, moody screen-prints on PVC of himself posing as a legendary hero/religious figure. Brothers Hossen and Hassan Sharif (UAE) offered intriguing conceptual assemblages; and artists/theorists Bilal Khbeiz, Tony Chakar and Jalal Toufic worked the vein of cross-conceptualization in deft interplay. (All three were represented at the Documenta XI.)

Other works that stood out included Norwegian Morten Loberg’s large format black and white photographic prints, distanced surveillance-like shots of trucks traversing tall bridges. They suggested dread and disturbance while blurring into abstract freezes. Derek Ogbourne (United Kingdom) offered a mad, 29-minute video of an endless freefall of hands slipping out of control. It was totally engrossing despite the rough-cut style. Jim Coverely (United Kingdom) showed stunning steel and latex sculptures of morphing shapes; his countryman Chris Grottick also showed shape-shifting images, of plants, vases and windows in a London park. Madeline Strindberg’s (United Kingdom) war paintings of silver helicopters on orange backdrop, and a huge cartoon of lemons with razors embedded (American war journalism?) were up to the task of confronting the Iraq War hysteria and its nasty outcomes.

Concurrent with the Biennial was an intensive three day, six session symposium entitled: “Art In A Changing Horizon: Globalization And New Aesthetic Practice,” organized by Talal Moualla, with simultaneous Arabic/French and English interpretations. This brought art historians, philosophers, theorists, artists, writers, and curators together for spirited discussions on the papers presented and the current state of political/cultural affairs within the Islamic world; and between their world and the West. Violence was featured prominently in the intense discussions as the US Army invaded and occupied Iraq. Strong, passionate debate ensued and one felt that new groundwork was being laid at this historic moment of political crisis throughout the Middle East. One also felt that the world was teetering toward apocalypse.

In “Caretaking Civilization,” one writer felt that civilization as a whole was being attacked, and that Islamic and Western countries were not being allowed to build their own cultures due to being marginalized and overwhelmed by violence with the USA/Iraq war and the high level of violence pervading popular culture. There was a fear of growing dehumanization of Arab and Western societies due to the influence of fanatics on both sides driving for violent solutions to political problems.

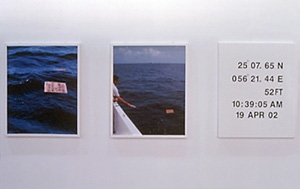

Some of the topics of discussion: we learned that there were thirty to forty fine art galleries in Iraq (nine well-established) before the 1980s and artists in Iraq were still producing art despite the great economic and political problems, even though most creative artists were forced to leave Iraq in the 1990s due to the economic depression and the repressive Hussein policies. In neighboring Tehran there are numerous art galleries exhibiting contemporary art. Contemporary art is a facet of Islamic culture, but older historical Islamic arts still have resonance and power within Islamic culture. American and Western arts have greatly influenced Islamic artists, but the Islamic world wants its own ideas, concepts and its own objective reality to be recognized. Segregation of contemporary art and older Islamic art is a dangerous policy that creates ghettoized categories while reducing previous world wisdom to mere opinion. Islamic art has a power base foreign to the West. Modern trends tend to nullify/demystify religion on both sides. As America pursued the destruction of Iraq, many issues were overlooked, such as the entangled nature of art and politics, art as the assertion of self-hood, and the fact that art can clarify values. Also one critic said the first Iraqi/US war was a war without place or name as there was no sense of glory or history involved in the massive American aerial bombardments/massacres (maybe only GPS coordinates).

The diverse opinions that were expressed made us keenly aware that, just as the peace activists are shut out of US media coverage/debate, many Arab political opinions are ignored. The Sharjah Biennial was a successful effort to overcome this violent status quo by openly dealing with these crucial issues.

© 2003, Christopher Kuhl

The Sixth Sharjah Biennal took place from April 8-May 8, 2003, in Sharjah, in the United Arab Emirates. For more information visit www.sharjahbiennial.com.