Feature: Essays

The Unbearable Lightness…

Without even trying, I have become an Art Grinch. I didn’t start out that way. Six years of art exhibits in San Francisco have done it to me. I reached my breaking point in 2001 at an opening for a certain wheat paste and sticker artist known for plastering smiley-faced beasties all over the Mission District. As a Mission resident, I was actually quite fond of these happy folk grinning at me from telephone poles, mailboxes and newsstands. They gave me fleeting moments of playfulness in a neighborhood that can be grim and gritty. So I entered the gallery with an open heart, ready to receive the work in the fullness of its various merits.

As I entered, a person in a rented fuzzy rabbit suit waved and welcomed me to a table of sweets. His goofball costume caused my eyes to glaze over and a delicate gray cloud to form over my head. As I stood before a grid of over 150 relentlessly happy folks batting their eyelashes, waving their tentacles and rolling their eyes at me, the cloud thickened. Without context, there is no magic. The magic of these familiar street poster smiley faces evaporated beneath the glare of the gallery lights. The Grinch began to assert himself.

“This guy can probably knock off two or three of these paintings a day,” I thought.

“Art is not piece work,” I countered. I continued looking around. The gallery patrons seemed happy and there were plenty of red dots going up next to the works. “Maybe I just don’t get it. Maybe I’m too jaded, too mired in old school thinking to see the transcendence of a big, blue, balloon-headed octopus-thingy with shiny Mickey Mouse eyes.” The cloud rumbled above my head. I congratulated the artist for working hard, and I meant it.

I studied the art one last time. It was like kindergarten painting – except instead of being innocent, it was naïve. No, wait, it was the opposite of naive, it was knowing. The problem, I decided, was that what it was knowing was simply not of interest to me. I grabbed a fistful of chocolate Easter eggs from the reception table, and walked out the door just as my cloud began pissing down on me.

Before I continue this rant, I will put my cultural cards on the table. I do this out of distaste for cultural critics who adopt the “voice of God tone,” designed to make it seem that their words waft down from some Mount Olympus of cool objectivity. I am Chicano and queer and an artist, and my various tribes have alternately used art in the following ways:

–they made art as a sacred act;

–they used art as bread on protracted political marches;

–they lanced themselves through with art to relieve deadly pressures that were often more than just flatulence;

–they used art to finally see a beauty that honored their lives;

–they used art to counter governmental, religious and commercial efforts to render them invisible or unacceptable;

–they used art to access an affordable pleasure.

Sounds serious, didactic and flat-footed, does it not? Sometimes it is, but in the right hands, it isn’t. Seriousness does not preclude wit, playfulness, aesthetic innovation, and intellectual panache. In the past four decades, we’ve certainly seen artists who execute this kind of work to the delight of many. In publications like Juxtapoz and galleries like La Luz de Jesus of L.A. or 111 Minna in San Francisco, you see some of the better practitioners of this school. But in 2001, I am struck by the gawdawful abundance of lightweight art filled with rampant, unearned irony. This concerns me because it seems that this aesthetic is becoming my generation’s signature contribution to visual art of the turn of the century. I speak out about this now because I do not want to be confronted in the year 2030 by a teary-eyed granddaughter asking “Grandpa, what were you doing when art was going to hell, you didn’t just let the lightweights ruin art, did you grandpa?”

You know the art I’m talking about, that sniggering, winking, elbow-to-the-ribs clever stuff. The subtext is usually “I’m so NAUGHTY!” I call it media baby upchuck. This is art that places media imagery at the center of all considerations. Love, desire, beauty, friction and fantasy are all funneled into a great pop meat grinder. The aesthetics, pacing, priorities and imagery of television and magazines reign supreme here. Again and again, I see artists taking their cues from popular mass media design and aesthetics.

The overriding influence of media on this art seems to give the work two priorities:

–make a visual impression that is fast, but not deep;

–never embarrass yourself with any signs of passion for content, ideas or materials.

Infantilism is the other main component of this work. The inner child has busted loose and established a new regime in San Francisco art venues ranging from coffee shops to commercial galleries to non-profits and art palaces. Beneath the tasteful glow of gallery lights, Mickey and Superman run rampant alongside big-eyed Japanese anime folk and snippets of Scooby Doo, Barbie, Barbie and more Barbie. Caca-poopoo-diaper-doo-doo rules. Stuffed animals appear in abundance. Their countenance, however, becomes charged with adult intent. Infancy and childhood can be amazing subject material for art, but media babies have a key handicap – they don’t watch people, they watch TV.

I do not question the importance and centrality of media and media images. I understand that we are awash in images whose only function is to sell. I see that this should be of concern to artists and non-artists alike. I know that when done correctly, media-driven, infantile art can be great. Andy Warhol was amazing at this. In more contemporary times, Bettye Saar and Enrique Chagoya have nailed this kind of work as well. However, what the current practitioners often fail to understand is that Warhol, Saar and Chagoya all created work that sprung out of strong cultures of opposition and thoughtful critique. They were either queer or black theorists or feminists or inheritors of Latin American leftist critique and they had fabulous instincts. Their icons, images and techniques flowed from those wellsprings. Media baby artists seem to think it was all just an aesthetic choice, ignoring or disregarding the contextual roots of their art.

Many artists do not see this as a problem. Indeed, media babies are proud to aspire to television’s slick flippancy, and exhibition venues and the media are quick to pick up on the sensationalistic quality of this work. It is a vicious circle. In the June 11, 2001 SF Bay Guardian Paul McEnry wrote an art cover story entitled Jackass Art in which he recounts how San Francisco’s “new school of brainy pranksters” is making art “fun”. He notes how artist Tim Gordon hammers a pen into his nose and does drawings. The cover image of the issue features Gordon hunched over a nose drawing, but nowhere do we see an exploration of the surprisingly good work itself. Artist Keith Boadwee self-administers an enema and then evacuates his bowels onto canvas to create paintings. The reception of Guy Overfelt’s art exhibit called Free Beer features just beer and people. The reception was in honor of the reception, that signature social ritual of the art world. This concept has some interesting possibilities, but the article never seriously interrogates the motivations of the artists because it is too busy recounting their naughty shenanigans.

In the article, McEnry mentions again and again how fun the art is and what a great party it makes. That’s all good, but what he never mentions is that the work changed him, greatly enriched him or seriously challenged him. The work has scarcely warmed his brain. It just momentarily entertained him. If that’s all he, or we, are to demand, why not just frequent frat parties instead of art openings?

Maybe a few decades ago, this art would have even been scandalous and thought provoking, but in 2001, everyone is a goddamn rebel, the marginal is pulled back into the mainstream before it even reaches escape velocity. There is hardly anyone left to shock. Artists, curators, art instructors and gallery aficionados are all stumbling over one another to be the hippest, most jaded and frosty of the bunch. In the words of Aretha Franklin, “who’s zooming who? “

Maybe this is the art our culture deserves, and maybe this is all we’ll get, but I hope not, because that would be like living on visual junk food. This is an aesthetic wave, and it too will pass. In the meantime, I’ll keep my eyes open for artists who are ready to get down with some serious fun.

FIN

Epilogue:

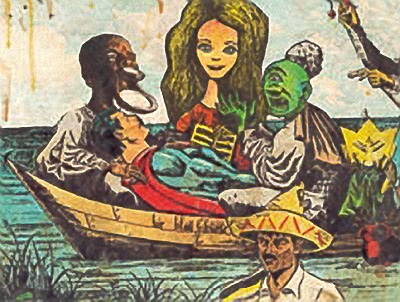

This article was written in the month before the September 11 attacks. Like everyone else, I am taking stock of how things have and have not changed. The pendulum has abruptly swung away from irony in an arc that is far wider than we ever imagined. In San Francisco, this shift was marked on November 4th. The event was called the Death O’ Irony Funeral, Wake and Barbeque. “Irony has been proclaimed dead by those most in touch with it, journalists.” the E-vite stated, “In order to bring the age of irony to an official end and welcome the generation of sincerity, we will be holding a funeral, wake, and barbeque – bring meat, booze, and something ironic which, obviously, has lost all value. The boat will be waiting to send your goods into Valhalla.”

This ironic sentiment was eerily repeated in the pages of the November, 2001, issue of Artforum. In the article “Moving Pictures”, writer Adam Lehner focused on artists and galleries responding to the terror attacks. He wrote of the Postmasters Gallery exhibition of video artist Wolfgang Staehle’s 2001, a live video feed of lower Manhattan seen from the East River. Every four seconds, a new image would come through the video feed, creating a motion picture that functioned almost as a landscape painting. On September 11, the gallery staff watched the horror blossom on the live video feed. When asked about the event, Staehle stated that “certain people, Americans with a certain sensibility, regret that the possibility for irony is gone. They want to be light-hearted. I have less tolerance for frivolous things. The way I look at art has changed . . . and Magda (gallery owner) said she would rather have this piece up now and not some bubble paintings. But really, it’s too early to talk about it.”

In the article above, I called for an end to easy, flippant irony. I got way more than I asked for. The age of neo-gravity has dawned. Are you ready?