Feature: Reviews

UC Berkeley MFA 2007

- Berkeley Art Museum

- 2625 Durant Avenue, Berkeley, CA

- Through June 10, 2007

fer · ma · ta

Berkeley Art Museum

2625 Durant Avenue, Berkeley, CA

Through June 10, 2007

The title of fer · ma · ta, the 37th edition of the annual University of California Berkeley MFA graduate exhibition, refers to a musical pause of unspecified length. Identifying a unifying principle in an MFA exhibition usually requires taking a view so broad as to be meaningless, but the fer · ma · ta curator, Miki Yoshimoto, found a serviceable hook. With a unanimity that is almost disconcerting, six of the artists in the exhibition emphasize absences, discontinuities, and gaps. I suppose it’s inevitable that when the country’s leaders specialize in lies, obfuscations, and evasions artists responding to the zeitgeist would come up with handfuls of nothing.

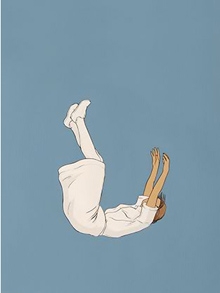

Jenifer K. Wofford colors her black line drawings with flat hues for an effect reminiscent of the childrens book illustrations of L. Kate Deal or the comics of Chris Ware. Her suite of drawings, Point of Departure, is a highlight of the show. It follows a fractured narrative line, as if the individual drawings were pages torn from a graphic novel. Most of the story is missing, but Wofford gets a bit of narrative drive going through skillful use of gesture and composition.

Kara Hearn’s video, a collection of quotidian incidents in which she plays every character, also contains some skillful gesturing. Like Wofford’s work, it’s a series of narrative scraps. Whether or not you watch every one of the disconnected skits will depend on how much you enjoy watching Hearn differentiate herself from herself. If you loved Anthony Goicolea’s photographic tableaux, you might love Hearn’s work. Or you might wonder how much juice there is left in the depiction of multiple personalities.

The “plot” informing Wofford’s and Hearn’s works is elusive, but there seems to be one. Lindsay Benedict and Bill Jenkins, on the other hand, confront “something missing” directly, if not necessarily successfully. The exhibition essay claims that Benedict “aims her camera and microphone at the unheard voice.” The relationship between the glossy photographs on display in the gallery and this statement was unclear, but they did not suggest “moments of silence.” Like sound, color is a vibration, and if the “voice” of a narrator was silent, the bright, juicy hues of the photographs set up a clamor. Jenkins’s installation, Study for a Fountain, spaced a few worn objects at wide intervals around a sheet of dark construction material held down by part of a rock. The reference to Duchamp’s 1917 Fountain also seems worn. Jenkins makes his point, but he doesn’t make the viewer care about it. The difficulty may lie in the crowded installation. This piece needs its own space.

In a series of “UFO” photographs, Joe McKay appears to have digitally erased elements of a common scenes to create “UFO” sightings. He took away the post of a streetlight, for example, to make the lamp itself hover in the air over a parking lot. In a shot framed to eliminate spatial cues such as overlapping areas or other nearby lights, he does manage to dislocate the lamp and make it strange. A less tricky but more substantial work was shown as a video loop on a flat panel display. McKay aimed his camera on the pattern of light and dark cast by a freeway; there’s a moment of surprise when the shadows in what first appears to be a backlit photograph flow into motion with passing traffic. The video and photos both point to the process by which we infer the existence of things we do not see.

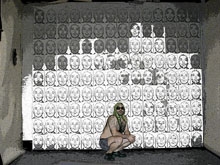

Ali Dadgar’s installation is full of stuff to see—it’s the biggest work in the show. A row of paper and rock piles fronts a big wall covered floor to ceiling with more papers and cut-outs. Dadgar treats a different kind of absence, lack of communication. He lays Persian text, ink blots, and other imagery over English texts, juxtaposing imagery and text in mutual interruption and disconnection. The scale of the installation seems grandiose, but it’s hard to argue the importance of his subject.

In this company, Alicia McCarthy’s drawings and paintings stand out as something different. Alone in her cohort, McCarthy is on to “something” rather than obsessed with “something missing.” She limns abstract tangles or crystals on found materials such as old wood panels and stained papers, interacting with the idiosyncratic marks on their surfaces. It’s refreshing to encounter her sense of agency and pleasure; her recycler’s esthetic brings a note of hope into the exhibition’s anxious chorus of absence and loss.