Feature: Reviews

Waiting for My Man: Warhol Live

- the de Young Museum

- San Francisco

- February 14, 2009 - May 17, 2009

Andy Warhol in the Spotlight

Andy Warhol’s phenomenal body of work spans paintings, prints, photography, sculpture, installation, film, video, magazines, TV shows and, one might argue, the sustained performance piece which was his life. His work remains fresh; recently two ambitious exhibitions appeared which explore the breadth of Warhol’s work and influence: “Other Voices, Other Rooms,” and its kissing cousin, “Warhol Live.”

“Other Voices, Other Rooms” gains its title from the Truman Capote novel of the same name. Capote, on whom Warhol once had a huge crush, wove a tale of alienation and longing which struck a resonant chord with the young artist. “Other Voices, Other Rooms” was conceived by curator Eva Meyer-Hermann to revisit Warhol, whom she perceived as largely reduced to the icon of a tomato soup can or Marilyn portrait, as the astoundingly complex, diverse, and influential artist which he was. From the Stedelijk in Amsterdam, it traveled to two concurrent venues, the Hayward in London, and the Wexner Center, at Ohio State University in Columbus.

My first stop at the Wexner Center was the Screening Room, where I discovered Tarzan and Jane, Regained…Sort Of (1963). Entering the pitch dark space, I took a seat to watch a murky grainy video of Taylor Mead and Naomi Levine sloshing around in a bathtub. Soon, the scene shifts; the irrepressible, goggle-eyed Taylor emerging from a makeshift trailer in some dirt-poor rockscrabble location, resembling rural Mexico. Mead is wearing what looks like a g-string, a black leather belt or harness—something designed for man or beast— and nothing else. He dances manically while artist Claes Oldenburg stands by. This is what personal freedom is about. And, certainly, exhibitionism. Warhol tapped into the exhibitionist tendencies of egomaniacal extroverts—and made them Superstars.

In San Francisco we find Stéphane Aquin’s “Warhol Live,” originally mounted at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montreal, where he is curator of contemporary art. From Quebec it traveled to the de Young, proposing the theme of music as a critical, if not the primary, motivating factor driving Warhol’s work. From the start, the de Young exhibition gives more emphasis to real stars: gunslinging Silver Elvis (1962), a signed portrait of Shirley Temple, Gold Marilyn(1962), as well as portraits of Judy Garland and Liza Minnelli.

Warhol, with bad skin, thin hair and thick glasses, along with fey persona, was not physically glamorous or sexy— yet he created the sexiest art, his body of work substituting for the hot physical body he lacked. He also became “twinned” with a number of beautiful companions, such as waif-like Edie Sedgwick, the pair creating a white-hot gestalt.

Iconic on so many levels, Andy Warhol evokes the turbulent era of the 1960s and 70s. Viewing the extensive collection of record album covers designed by the artist in “Warhol Live,” even without the pulsing rock soundtrack, would be enough to cause a massive rock and roll flashback. In particular, the award-winning Rolling Stones Sticky Fingers (1971) album cover, with its provocative zipper, captures the brash, sexually charged energy of the era, and must stand along the artist’s most potent work.

Warhol had an intense involvement with the Velvet Underground, and mentored its poetic lead singer, Lou Reed. To the dark and brooding sultriness of Reed, Cale, Morrison, and Tucker, Warhol added Nico, a statuesque and otherworldy pale beauty. As Warhol had publicly given up painting at this time, his energy was largely channeled into staging the multi-media experience Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable with The Velvet Underground (1966-67). With their aggressive stage presence and edgy material, they were the essence of punk, a decade before the genre would exist.

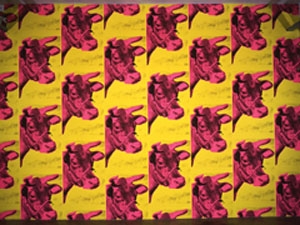

Along with soup cans, Warhol is perhaps best known for the quotation “In the future everyone will be famous for 15 minutes.” Now, with reality shows taking over the TV, and YouTube offering fame to one and all, his statement is strikingly prophetic. The Silver Factory (1964-1968) epitomized the revolutionary spirit of the times, with massive doses of sex, drugs and rock and roll, as the fame-seeking, wildly eclectic Superstars filtered in and out. Warhol is guilty of a certain amount of passive-aggressive encouragement, in a sense giving absolution to emotionally fragile and self-destructive types. Yet his role in the activity at the Factory was less that of orchestrator than observer, his stance appears to have been one of non-judgmental support, and a sense that ultimately you can’t control people. The exchange of high-voltage energy and ideas which bounced around this amphetamine-fueled world stimulated what is arguably Warhol’s most creative work, including the Brillo Boxes (1964), the Jackie series (also 1964), the Cow Wallpaper (1966), the lyrical Silver Clouds (1966), and his staging of the EPI happenings, along with the bulk of the artist’s film production— a body of work which curator Meyer-Hermann maintains is his strongest.

His audacious elevation of the commonplace into the arena of fine art his generated countless disciples, including Jeff Koons and Takashi Murakami; his adoption of mechanical reproduction as a painting tool transformed the definition of the medium. His obsessions with money and death, paintings of cash, skulls, and disasters, clearly resonates in the work of contemporary artists such as Damien Hirst, with his vitrines of pickled livestock and diamond-studded skull, Marlene Dumas, with her Dead Marilyn (2008), among other corpses, as well as Gerhard Richter, with his murdered Eight Student Nurses (1966) and Baader-Meinhof Gang series (1988). Warhol’s tireless promotion of his public persona clearly found an heir in eccentric Martin Kippenberger.

Sex and gender issues form a subtext for most of the artist’s work from the beginning, particularly in the films, notable examples being My Hustler (1965), a film about a male prostitute, one which predated John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy (winner of Best Picture for 1969), a film which incorporated some Factory regulars as extras, and the eccentric Lonesome Cowboys (1968), which explored homoerotic themes in the Wild West— nearly 40 years before Ang Lee. Other films, such as Sleep (1963), Eat(1964), Kiss (1963-64), Haircut (1963), and Empire (1964) are more minimal in nature, plotless and silent, filmed with a stationary camera.

“I’ve been quoted a lot as saying, I like boring things, but that doesn’t mean I’m not bored by them… Because the more you look at the exact thing, the more the meaning goes away, and the better and emptier you feel.” (Warhol) In the Sound and Vision section of “Warhol Live,” Aquin explores the artist’s relationship to the work of avant-garde musician John Cage and choreographer Merce Cunningham. Warhol, perhaps unwittingly, seems to have tapped into the essence of Zen meditation. Cage, who clearly influenced Warhol, was an active student of Buddhism; his 4’33” (1952) where the musical score is for four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence, with the ambient sounds shaping the piece, conveys his perception of the evocative potential of emptiness. When Warhol drifted into the emptiness of boredom, he was certainly close to the state attained by meditation, and how might we gauge the difference between the two? Warhol’s use of repetition, of endless stacks of Brillo boxes or row upon row of Coke bottles, reinforces the idea of a mantra, a repetitive chant for quieting the mind.

The spiritual core of Warhol, perceived by many as an opportunistic party animal, deserves greater attention. Warhol the man is largely obscured by the layers of camouflage with which he faced the world. His wigs, his makeup, his entourage, not to mention the constant companion, his tape recorder (which he jokingly called his wife), and finally, his public persona, the cool monosyllabic icon with the aloof stare. A man of striking contrasts, brilliant, but verbally challenged, sensitive, but sometimes invasive. Religious at heart, but profane by action. Painfully shy, yet thirsting for fame.

Warhol liked to hide behind a mask of naiveté, of being shallow and indifferent. He was shallow, to the extent that he was obsessed by fame, and could let his curiosity overcome his higher nature on countless occasions. Yet, as we look, we may find in his work sensitivity and depth of feeling—etched in the line of his drawings, reflected in his compassion for all manner of extreme types, and resonating in the empty spaces where his work allows our minds to float downstream.