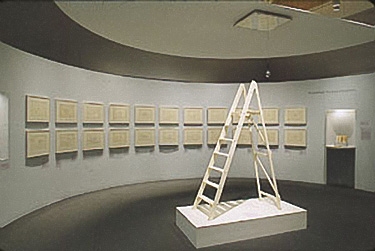

Forground: Ceiling Painting (Yes Painting) (1966), Yoko Ono, Text on paper, glass, metal frame, metal chain, magnifying glass, painted ladder. Installation at Japan Society Gallery, New York. Photo by Sheldan C. Collins. Collection of the artist © YOKO ONO. Background: Instructions for Paintings (1961), Yoko Ono, Series of 22 works first exhibited at Sogetsu Art Center, Tokyo, May 24, 1962. Installation at Japan Society Gallery, New York. Photo by Sheldan C. Collins. Collection of Gilbert and Lila Silverman, Detroit.

Feature: Reviews

Yes Yoko Ono

- Originated by Japan Society Gallery, New York

- Traveling throughout United States and Canada through 2003

Editors’ note: In Antonia Fraser’s recent biography of Marie Antoinette, she exposed the misogynist vilification of the French queen by the public. Centuries later, Yoko Ono endured the Marie Antoinette experience; after her marriage to the “king” everyone hated her but no one knew her. She was catapulted from a cozy circle of avant-garde friends into an international mob of media sharks. What comes plainly through her retrospective, Yes Yoko Ono, is the consistency with which she continued to chase her vision. The videos, music, and media events Ono and Lennon made together are natural developments of her previous work. Celebrity and cerebral art are an unstable mix; Ono demonstrated ingenuity and even bravery in adapting to her situation, just as Marie Antoinette was sustained by her dignity. Ono’s story seems headed for a happier ending; her retrospective is traveling worldwide. In the following review, Dore Bowen discusses the exhibition as it appeared at the Japan Society in New York; after completing a run at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art September 16, Yes Yoko Ono continues on to the Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami.

Trouble in Tooltown

The exhibition 101010:Art in Technological Times, which closed last July at the SanFrancisco Museum of Modern Art, treated viewers to a multitude of works that concern the impact of technology. Yet, rather than defining the technological nature of "our times," the exhibit begged a primary question looming over our post-cyber-euphoric moment: What precisely is technology? I have a proposition that flies in the face of logic (but then, logic maybe the problem, not the answer): technology is not a particular kind ofobject (with circuits or electricity or chips), but a relationship between humans, our tools, and our goals. A computer, for instance, can only do what we imagine it ought to. Our imagination is the key. Happily, San Francisco will be treated to an exhibition at SFMOMA next summer that, while concerning the relationship between technology and society, transposes the question into another key — Yoko Ono’s retrospective Yes YokoOno.

Unlike much work being produced and exhibited today, Ono focuses our attentionon the most common of tools. She tempts us to loosen our assumptions with a Sky Dispenser (1966) or a Box of Smile (1967). In her well-known Ceiling Piece (1966), the seeker’s journey up a ladder is rewarded with a benevolent "yes." Yet the word can’t be easily read. A magnifying glass hanging nearby must be used, reminding the viewer that it is their desire to know and see that carried them to this moment of affirmation. By extension, Ceiling Piece encourages us to ponder where we’re heading on the technological super-highway, emphasizing the visual nature of this quest by linking spiritual affirmation to the seeker’s curious gaze. On the other hand, what is finally found is a word, not an image. This substitution makes the mental nature of vision apparent.

Ono’s Instructions for Photographs (1961-1971) offer another angle on this theme. These haiku-instructions don’t exist as aesthetic objects, but instead act as instruments for producing an internal photograph. Our mind does the work.

Time Photo

Make a photo in which

the color comes out only

under a certain light,

at a certain time of the day.

A “time photo” is an opportunity to think our relationship to light and color. This mutable relationship, rather than a particular image, is what Ono asks us to consider. While Time Photo involves the beholder’s perceptual share, Conversation Piece (1963) concerns the way photographs are interpreted against a larger social horizon.

Conversation Piece

Talk about a death of an imaginary person.

If somebody is interested,

bring out a black frame photograph

of the deceased and show.

If friends invite you, excuse yourself

by explaining about the death of the

person.

Acting as a tool, a catalyst, a conversation piece, the photograph is employed here in order to address the issue of death. Presumably, the friends will respond with sympathy to a photograph of a deceased person. The bearer of the photograph then will be able to talk on at length and, ultimately, excuse herself from social activities. Thus the context of the image informs its interpretive meaning. Death is the “black frame” around the image.

For the invitation to her exhibit This is Not Here (1971) at the Everson Gallery in Syracuse, Ono sent out invitations that were printed on a sheet of photographic paper that was partially fixed, then folded. Once the invitation was opened and exposed to the light, the image faded, leaving only Ono’s name and a telephone number on the reverse side. The recipient was left with a blank sheet of paper and an afterimage of its contents. This is the confrontation with what Ono calls "wonderment." Things pass, even photographs. All grasping for permanency ultimately fails. We are left with soap bubbles. Why not play with them? For Ono, the photograph is a tool with which to picture our world, mediate our desires, fulfill our goals, and yet it too exists in flux, perpetually afloat and ridden with life.

Ono’s airy approach to weighty matters has a hint of the radical in it. In Kite Piece (1963) we are instructed to make kites out of photographs, fly them, and then ask others to shoot them down. In Horizontal Memory (1997), viewers must step over and on anonymous family photographs in order to enter the gallery. Such works call for us to act upon images, even destroy them, rather than respectfully absorbing them like couch potatoes on a soma holiday. But, you may ask: can this concept empower us to alter our increasingly dependent relationship to the media (the diorama of alienating corporate-sponsored imagery)? While phantom images haunt us, the physical and mental labor that we invest in them is often invisible. Ono brings this labor to light. The sentiment of Ono’s work, for all its utopian pretensions, is pragmatic. We make images; only when we forget this do they seem to make us. For example, Ceiling Piece reminds us that it is our feet that transport us up the ladder; it is our hands that grasp the lens to make the word near; it is our aspiration to see a distant ground which initiates the journey.

Yes Yoko Ono originated at the Japan Society Gallery, New York and is on view at the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston, Texas through September 16. The exhibition travels to the MIT-LIST Visual Arts Center, Cambridge, Massachusetts October 18th-January 6th 2002; Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada, February 22nd-May 20th 2002; and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art June 22nd-September 8th 2002. After closing in San Francisco, it continues to the Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami. For more information and updated tour information, visit http://www.mocanomi.org