Feature: Reviews

8th Havana Biennal: Art and Life

- November 1 - December 15, 2003

By Jennifer McCabe

Despite serious financial difficulties, further complicated by the withdraw of important European financial support, the 8th Havana Biennial opened showing work by approximately 150 artists from so-called Third World countries: Asia, Africa, the Middle East, the Caribbean, Central and South America. Since the Biennial’s inception in 1984, the intent has been to showcase contemporary art from Third World countries, while exposing Cuba to the international art scene and providing a platform for launching contemporary Cuban artists into the art world. This year the Biennial’s main organizer, the Wilfredo Lam Center of Contemporary Art (Havana), invited foreign artists and experts to curate the exposition titled Art and Life. The opening week of the Biennial was dedicated to a forum discussing the theme which the artwork purported to embody.

However the interpretation of “art and life” can vary remarkably depending on one’s life perspective. The work of participating Biennial artists regularly confronted difficulties associated with life in less economically developed countries, where politics, survival, and perseverance are an inseparable fact of the life of artists. This is most evident in Cuba, an already isolated island further disconnected following the apparent EU alignment with the US to support pro-democracy dissidents to the Cuban government.

Culture and politics cannot be separated and the effects are far-reaching. In her catalog essay “A Biennial Focused on Hope”, Hilda Maria Rodriguez, director of Wilfredo Lam Center of Contemporary Art, states that the aim of the 8th Havana Biennial was to go beyond conventional art spaces and join other international events that explore the incidence of art in cities, public spaces, and the relationship between art and reality. Indeed the Biennial showcased numerous ways to explore non-traditional art spaces. For example, in Havana’s eastern end, Alamar (Cuba’s largest housing project), 15 artists, architects, and designers transformed 13 living spaces. Incorporating an approach similar to the television show “Trading Spaces”, the artists worked with the residents to ameliorate their living conditions with re-organization, paint, or objects of art. At La California, a former slum in Central Havana, a project with Cuban artists under the leadership of Roberto Diago, Manuel Mendive and Eduardo Roca Salazar (Choco) offered a space of exchange that included workshops, in an attempt to involve neighbors often neglected from participation in the arts.

Aside from the plurality of non-official sites of intervention, which included the aforementioned slums, as well as a deserted church, galleries, and studios, there were also several main arteries of exhibition: the Fortaleza de San Carlos de la Cabana (with 90 participants), Centro de Arte Contemporaneo Wifredo Lam, Pabellen Cuba (4D, a project by the group RAIN), Centro de Desarrollo de las Artes Visuales (Cuban art exhibition), Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes (featuring Tania Bruguera, Los Carpinteros, Rene Francisco Rodriguez), and La Casona (featuring Carlos Garaicoa, Luis Gomez, Esterio Segura).

Concurrent with the theme, many artists featured at the Fortaleza de San Carlos de la Cabana attempted to blur the boundary between the artistic and the common. Chilean artist, Claudio Correa chose the public space of a bathroom as the location for Autosuficiencia (Self-sufficiency), revolutionary imagery appropriated from the murals of Mexican artist David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896 - 1974), who was not only a political activist but also a supporter of Castro’s Cuba. Correa paints a large sink with imagery from Siqueiros’ mural, Portrait of the Bourgeoisie, of a French parliament building ablaze. As fire ravages the building, the flames aggressively burst up the wall behind the sink, ultimately transforming into smeared handprints. Miniature marching armies painted along the walls continue from the sink and multiply as they enter the men’s and women’s toilets. The insides of the toilet bowls are painted with more of Siqueiros’ images from the murals, The New Democracy, and Our Present Image. Although submerged in water, Correa’s paintings are rich in color and realism. The captivation of this work lies in its ability to elicit multiple readings. Placing artwork in a public bathroom calls into question the boundaries between the common and the artistic, advocating convergence of art and life. The placement of revolutionary imagery (not to mention the title) reads as political commentary, as in the depiction of a man whose face has been replaced by the hole of the toilet.

Many Cuban artists referred to their country’s present situation. Geysell Capetillo’s Contencion (Containment), manifests the urban decay of Havana. Water traverses through a system of pipes suspended from the ceiling, harmoniously leaking into containers strategically placed to catch the leaks. Because old bathtubs, plastic buckets, and other makeshift containers collect the water, one could easily walk by the installation mistaking it for some kind of workroom. The installation at once recreates everyday reality and emphasizes the disappointment of unresolved problems.

Oil was another common Biennial motif, loaded with political commentary. Cuban artist Ivan Capote’s installation, Dislexia (Dyslexia), involves a spindly black machine that moves an arm through a shallow tray of oil. As the arm moves back and forth the oil separates briefly to reveal a sentence that reads, “Life is a text which we learn to read too late”. Cuban artist Alexis Esquivel employs witty political commentary with his use of the ubiquitous plastic chair (oil is used in the production of plastic). There is a saying in Cuba that they have no oil because they had no dinosaurs. Esquivel rewrites Cuban history by discovering and assembling the fossilized bones of a “dinosaur” from plastic chairs, creating a striking resemblance to a real dinosaur skeleton.

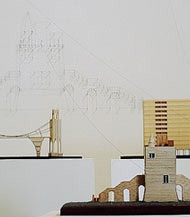

“Kill the Idiots”, written in spray paint loomed overhead at the entrance to the Cuba Pavilion, setting the tone for the experimental work within. 4D, a collaboration between the Wilfredo Lam Center of Contemporary Art and RAIN, a group of artists, architects, and curators founded in Los Angeles in 2000. The pavilion was originally conceived as an exhibition site for Cuban art works during the congress of the International Architects’ Association in 1963, and is located on one of the most important avenues - Vedado, in Havana. RAIN created an elaborate scaffolding structure running through the vast open space connecting the street to the farthest point of the pavilion. Within the scaffolding small exhibition rooms contained mostly video, works on paper, and installations. The main floor of the pavilion was left open for performances. Unfortunately, unless you closely followed the program or were coincidentally at the space at the right time, there was not much to see beyond the scaffolding. The inquisitive viewer could find a spectacular model of the scaffolding built entirely from drinking straws and cardboard. Notable artists were Torolab, who displayed a version of their Urban Survival Unit reconfigured to be effective beyond their native Tijuana. The Brazilian group Bijari collaborated in a series of interventions performed throughout the city that they documented in a video titled Accion Havana. A chicken was interjected into all kinds of inappropriate places and made for a few good laughs.

The work of some better-known artists stood out, although not necessarily embodying the ideas of art and life as projected by the Biennial’s curators. One such artist, Carlos Garaicoa (Cuba), exhibited La habitacion de mi negatividad (The room of my negativity) at Centro de Desarrollo de las Artes Visuales. The installation consisted of delicate, skillfully constructed models of imagined buildings. Upon closer examination, the viewer discovered a complex mapping of strings connecting the buildings to the wall, with pushpins and re-creating the architecture. The effect was magical, as if one element became the shadow of the other.

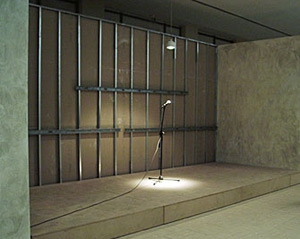

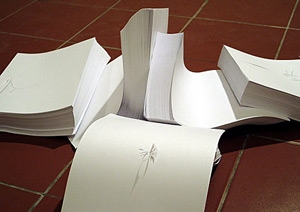

The Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes showcased installations by acclaimed Cuban artists Tania Bruguera and Los Carpinteros. The building itself was recently renovated under the leadership of architect Jos Linares Ferrera and contains a permanent collection of Cuban art from the colonial period through the 19th century, the 20th century avant-garde, and the new generations since the 1950s up to young artists of the 1990s. Tania Bruguera’s sound installation, Autobiografia, consisted of a makeshift wooden stage with a lone microphone that invited viewers to approach. Pre-recorded political slogans, such as “Freedom or Death” resonated through the room, allowing viewers to feel the power of the sound vibrations while standing on the wooden stage. Los Carpinteros installed Fluido in the gallery of the Museum, comprised of inflated elements of black polyurethane resin in the shapes of drops of liquid, perhaps oil. The colossal size of the drops embodies the societal importance placed on the liquid. Again, the political overtones of “life” dictate art.

Historically, the art and life connection has been widely debated. In a calculated move against modernism’s endorsement of aesthetic exclusivity, artists of the late 1950s-early 1960s attempted to reconcile the aesthetic with the everyday. Through Happenings, Fluxus, and anti-art, work emerged with the objective to close the gap between art and life. Artist and art critic, Luis Camnitzer historicizes the ebb and flow of these ideas in his catalog essay for the Biennial. He condenses the art/life continuum into forty-year cycles beginning with Soviet constructivist experiments of the 1920s and moving to the decade of the 1960s with Situational artists in France, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia; Happenings, Fluxus, and Warhol in the United States; and Tucuman arde in Argentina, among others. Presently, Camnitzer claims, we have Cuban artists and collective actions around the world, which work to reunite art and life, but who realize that politics must be added to the marriage.

Ultimately the curators of the Biennal expressed the wish to open dialogue, not only about specific works of artists, but also in their relation to the exhibition spaces and the urban environment of Havana. However, whether artists brought “life” into galleries or brought art into “life”, the execution of the work, under such a theme, was often too contrived. The strongest work seemed to exist not within these interaction/intervention sites of the community, but back in the traditional art spaces. In this sense the hope to erase alleged traditional borders between art and life was not successful. Nevertheless, the desire to link art with life remains, both in the past and now, as an ongoing revolt against established art practices. Perhaps now the revolt is against the commodification and internationalization of biennials, instead imbuing both art and life with the specificity of a locale and its politics, balancing the power between the two. As the Biennial demonstrates, art and life is less about the exhibition site and more about what is going on in our lives, seen through the lens of art.

(3) COMMENTS

how the fuck could you have TOTALLY missed the huge presence of san francisco artists that were showing work in the biennial? typical.

The piece that impressed me the most at the Havana Biennal was by the Cuban group Enema, at the Wilfredo Lam Center. It was a video with a vitrine. Inside the vitrine there were some medical materials, including a large syringe, some bloodied gauze, and a small jar containing a sausage preserved in liquid. The video showed the artists drawing their own blood, cooking onions and herbs, and then adding the blood. The resulting mix was sauteed and then poured into a sausage skin. Voil·, blood sausage, made from the artists’ own blood! It was a gruesome but telling piece, particularly for a country that is experiencing difficulties feeding itself.

Two members (I was told) of the Enema group, Elsoca and Fabian, had another strong (and easily overlooked) piece at the Centro de Desarrollo space, written on the wall around the inner entryway. This piece was made out of the wings of hundreds of flies glued to the wall, spelling out a text (provided in both the original Spanish and the following English translation on the label): “We were truly sordid and undesirable but today we pretend to be beautiful and nice, thanks to our sacrifice with enthusiasm and a lot of craft. We feel happy and elegant in this important mission” Again, this was a beautiful and heartbreaking piece…

Nice article, did u were there at the opening?

Actually, I have a qustion: did u see my works, photos: Global vs Local and the video performance: Local meets Local? I would like to know if the organiser really put my works at the pabellion, coz I couldn’t bring my self over there. Thanks a lot! Tiarma-Indonesia

Tiarma D.R. Sirait • January 07, 2004