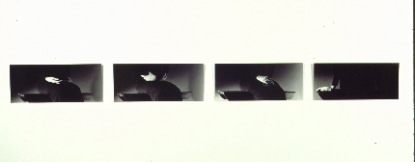

What do you tell and how do you tell it (I-IV) (1997), Amy Eshoo, four black and white photographs, 10 x 24 in. each

Feature: Reviews

Amy Ishoo

Minding the Gap: Amy Eshoo’s In-Between

Someone sits by herself, a person we cannot entirely identify. Her head is cropped out of the photo, or draped, or only its backlit shadow is caught on a suspended cloth. She may be gesturing with her hands, but there is no one else in the picture to respond to that gesture. Whatever communication the subject is attempting has failed — or perhaps the communication is only with herself.

Being alone is Amy Eshoo’s subject matter, which she explores primarily through photography. There is great irony in that approach: a photograph of a lone person is a peculiarly transparent fiction, since there is ordinarily someone else in the room to take the picture. Nevertheless, even if the people in Eshoo’s tableaux are not physically alone, they are certainly psychologically so. Sometimes there is no person at all, just a domestic interior caught from an odd vantage point that reveals household objects and cast shadows — never a kindred presence. What Eshoo captures so well is not the relationships shared by people and things, but the space around or between them.

Eshoo’s photos are almost exclusively black and white, varying in size from a few inches to several feet on a side. Their format is usually an elongated horizontal or vertical; sometimes Eshoo strings several of these together in a row, in a manner curiously reminiscent of serial works by such minimalist artists as Donald Judd. Whereas Judd applied his “one thing after another” composition to copper boxes protruding from the wall, Eshoo applies this serial treatment to severely cropped photos of a woman’s hands folded in her lap, hung unframed on the wall. Each photo shows a slightly different position of the hands, each gesture intimating a different — perhaps profoundly different — emotional state. Like Judd’s boxes, however, the events in Eshoo’s photos don’t progress toward any conclusion; while the sequence of discrete photos resembles a sequence of frames in a film, the lack of closure suggests a film loop rather than a traditional cinematic narrative. Looking at these photos feels like going over the moments again and again in your mind, trying to make sense of the succession of gestures.

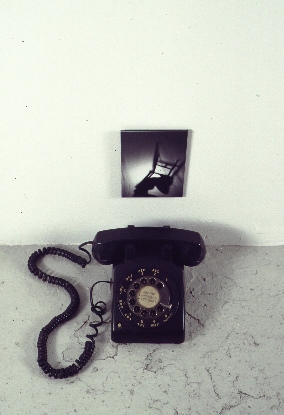

Sometimes the photos are augmented by something else, as in a recent work juxtaposing black quotidian objects with enigmatic photos. Lying in a row on the floor are a black notebook, a black ceramic phone, an antique, dilapidated black feather duster. Each is paired with a small, slightly blurry black-and-white photo sitting on the baseboard a few inches above the floor. The installation presents an interesting question: since the two components represent two different orders of experience — objects themselves and signs for objects — it would be tempting to read one as a prop for the other. Do the photos give a context for the objects, like didactic panels in a historical museum? Or are the photos meant to be the primary focus — since photos are still more coded as art than objects, despite a half century of bicycle wheels and bottle racks on pedestals? To her credit, Eshoo doesn’t resolve this tension superficially, but has chosen both object and photo very carefully so as to keep the meaning suspended somewhere between the two. While they are perfectly mundane and commonplace objects, the old-fashioned notebook, phone, and feather duster have a very particular emotional tenor — like furniture inherited from one’s grandmother. Meanwhile, the photos are deliberately flat and contextless, such as someone’s shadow caught on a backlit sheet.

Perhaps Eshoo’s best work in this series is a video showing a closeup shot of a woman’s hand repeatedly flicking a light switch on the wall. The woman’s gesture is slow, continuous, and gentle, in contrast to the abrupt on and off of the light in the room. Here the reference to a film loop is even stronger than before — not just because the video was originally made from a film, but because the alternation of light and dark mimes the interval between cinematic frames and their black borders in a stretch of celluloid film, light to dark to light to dark…. Every time I see the piece I stare at it for a long time — the work is hypnotic, not just in the sense that this simple activity becomes enticing to stare at for minutes on end, but also in the original sense of hypnos, the Greek word for sleep. For in this brief oscillation between on and off is the day’s diurnal cycle from light to dark. It just happens to be twelve hours out of phase, since we only turn lights on once the sky outside has become dark. Eshoo has captured all of this in a couple flicks of the wrist.

Or maybe it’s what’s between the flicks that counts — and what’s between the feather duster and the photo, or between the various gestures of the woman’s hands. By making the space (both literal and figural) between two objects more interesting than the objects themselves, Eshoo compels her viewers to squint intently at the in-between.