Feature: Reviews

Brides of Frankenstein

- San Jose Museum of Art

- San Jose, CA

- Through October 30, 2005

Curator Marcia Tanner’s thought-provoking exhibition at the San Jose Museum, Brides of Frankenstein, offers an unusual blend of technology and politics, with a strong feminist slant: it critiques our media culture, and its romance with technology, at the same time as lovingly embracing it. Tanner poses challenging questions about the state of humanity today, with our increasing dependence on electronics—our ubiquitous attachments to our cell phones, Ipods, PDAs and other gadgets, as well as our intimate involvement with digital images. Tanner states, “In this information-laden world, these works reflect the fluid, eclectic, and multitasking beings we ourselves are becoming.”

In Mary Shelley’s novel, Dr. Victor Frankenstein becomes obsessed with the idea of creating life from inanimate tissue; ultimately, the creature he creates, freakish and uncontrollable, becomes his downfall. Tanner views the fifteen female artists in “Brides” as the “metaphorical mates” of Frankenstein as they stitch together their various animated hybrids, and also as Mary Shelley, pointing out the hubris and folly of playing God. Nearly half of the artists work with some form of video; many of these are engaged in an exploration of the distorted images of women with which real women must contend. For decades, feminist artists and writers have tackled this issue—one that refuses to receive a stake through its heart and obligingly die.

In the first chamber, we find an assortment of pulsing, breathing, glowing objects. Andrea Ackerman’s compelling Rose Breathing: Version I is a large-scale video projection in which a sensuous, pink object blooms and then contracts to a soundtrack of deep inhalation and exhalation. Voyeuristically, we long to see what lies within. Also working with the pattern of breath, Sabrina Raaf presents Breath 1: Pleasure. A dozen circular units mounted on the wall, connected by umbilical-like electric cords, glow with technological life. Nearby, Gail Wight’s The Sirens, echoing butterflies and cocoons, hums and screeches on a circular platform.

Collaborative works by portrait sculptor Elizabeth King and photographer Katherine Wetzel, along with film director Richard Kizu-Blair, provide what is perhaps the show’s signature image, Pupil. A wide-eyed, poseable mannequin with a segmented neck, “she” appears vulnerable: frightened and frightening; beautiful, yet repulsive. A suite of elegant silver gelatin prints accompanies a video, where the eerily life-like mannequin gestures and expresses emotion in a disturbingly convincing way. This piece hits us emotionally at the core of the show—just how far do we remain separated from our increasingly sophisticated creations? Nearby, a nude figure, that could be her distant digital cousin, is found eternally descending a Duchampian staircase, Kirsten Geisler’s Dream of Beauty 4.0.

Addressing the technology and imagery of video games, more and more a kind of surrogate reality for many in our culture, are Peggy Ahwesh and Kristin Lucas. Ahwesh’s strangely compelling She Puppet repositions Lara Croft from the Tomb Raider game into a new, introspective video identity. Kristin Lucas’s 5 Minute Break also mines the territory staked out by Lara; Lucas also presents Involuntary Reception, a split-screen video featuring the artist as a quirky character unusually sensitive to high-frequency waves. For those feeling stressed by all of this, Adrienne Wortzel’s Eliza Redux: The Veils of Transference offers five minute interactive digital therapy sessions with “Eliza,” a robotic virtual Freudian psychoanalyst.

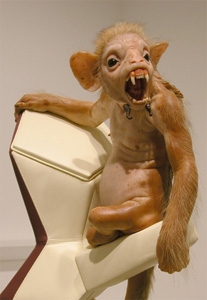

Heidi Kumao and Patricia Piccinini create menacing, yet humorous, animated, robotic sculptures. Kumao’s Protest uses little girls’ black patent leather tap shoes and mechanical legs to create an interactive work which stamps on the table in a moving, robotic tantrum. This work, defying “proper” behavior, is quite popular with adults and children alike, who revel in its loud, insistent clatter. Nearby, we may find animatronic sculptures of silicone, hog-hair and automotive components—Patricia Piccinini’s Siren Moles. Picinnini also presents In Bocca Al Lupo (In the Mouth of the Wolf) a video which features an eerie, flaccid display of biomorphic hanging objects, which go from a relatively calm state to irate and agitated. They vaguely suggest the half-formed head of Voldemort as embedded in the skull of Professor Quirrell.

Video facilitates works by Gail Wight and Camille Utterbach which use living beings in a more abstract way, as color, weight and form, Utterbach’s clever Shaken, From the Potent Objects Series, offers a snow globe; inside, a small LCD screen displays a woman who responds as if she, herself, were being shaken. Her engaging Untitled 5, From the External Measures Series allows the viewer to interact with a large computer-generated projection of a colorful abstract drawing—as we cross the space, our bodies create lines and strokes. In the adjacent space, Stanford professor Gail Wight presents a beautiful, subtle video triptych, Creep which records the growth of a particular variety of slime mold; its straightforward approach finds the mysterious side of a rather unglamorous living organism.

Helping to set the mood of Gothic horror, a “study” is created, with desk, oriental carpet and flickering electric candelabras. Much of the work on view reads more as science fiction than horror, still some works do cross over the line—Tamara Stone’s Ouch, a hanging installation of life-sized “pre-pubescent dolls,” with gauzy, shroud-like garments, and ropey tufts of wool hair. If you are so compelled, you may walk through these corpse-like constructions. Also presenting macabre imagery, Erzsébet Baerveldt’s Pieta takes the image of the Virgin Mary cradling the lifeless body of Jesus Christ as a point of departure for a video piece in which the artist, assuming the role of grieving creator, unshrouds a female figure made of wet clay. She gently and rather tenderly pries it from its plastic drape, as a solemn soundtrack, taken from Warhol’s “Dracula,” creates a creepy, somewhat funereal mood.

We may also view large, still digital photos by Sabrina Raaf which offer unusual and disturbing images of alternate realities where people defy gravity, exist with symbiotic insects, or find they share a bathroom with a band of mini-astronauts, and Amy Myers’s futuristic graphite, ink and gouache drawing which suggests a blueprint for some austere android.

Many of us respond, at one time or another, to a creative impulse. We feel the need to shape objects and/or living creatures, which will bear our stamp when we no longer have life or breath. For centuries, this creative impulse was, for women, largely confined to the areas of procreation and mothering. As women have evolved, along with the rest of our species, to demand a different set of variables for our lives, many of us ponder the infinite permutations possible. Brides of Frankenstein offers a deliciously chilling glimpse into seductive options for giving life to inanimate objects.

For more information on Brides of Frankenstein visit San Jose Museum of Art.