Feature: Reviews

Culture in the Making

- Hackett-Freedman Gallery

- San Francisco

- January 11 - March 3, 2007

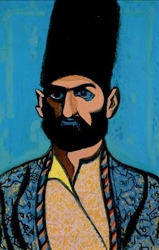

The Hackett-Freedman Gallery describes its 20th Anniversary exhibition of New York and Bay Area artwork from the 1950s and 1960s as an exhibition of “museum-quality” work by Andy Warhol, Jess, Louise Nevelson, Wayne Thiebaud, Manuel Neri, Richard Diebenkorn, Josef Albers, and many more. The works on display, the extensive catalogue, and the lengthy wall tags/biographies aim to relate all of these works by highly esteemed artists. However, it is also difficult not to be acutely aware of the fact that each of these pieces, mostly by artists who are no longer living, are being exhibited for sale to private collectors. Although they may later be donated to public institutions, in all likelihood, none of the profits will reach the artists. How much of the curation depended upon availability amd desirability to the consumer, and how much upon intellectual discernment?

Despite raising these initial personal qualms, the exhibition does attempt to provide a scholarly context to link numerous artists of the time period on both coasts. In Jed Perl’s preface to the exhibition catalogue, he concludes that in “what ways [the San Francisco scene] differed from what was happening in New York city is not easy to say.” Like Perl, I could not draw any generalized statement. Critics offer a variety of theoretical explanations to describe these differences, and yet none of them seem to hold true based on the works on display. Some attribute the essential difference to the different urban environments of New York City and the Bay: claustrophobic bustle versus San Francisco’s natural, earthy beauty. Another significant difference lies in the links that held the artists of New York and the Bay together. While the East Coast artists were held together by cafes and other social networking places, there was a formal institution linking those of the West Coast. The California School of Fine Arts — which became the San Francisco Art Institute — is mentioned in nearly all of the very lengthy wall tags accompanying each of the Bay Area artworks.

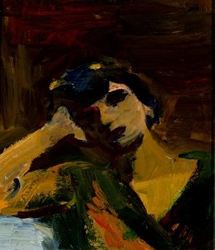

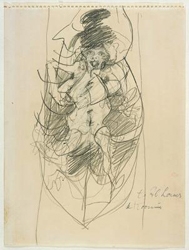

Despite these differences, I found that geographic labels were largely inadequate to segregate the styles of the East and West Coast abstractions. If one looks at the works on views without reading wall tags or the names of the artists, it is very difficult to discern a pattern that differentiates the artworks of each coast. Some abstract paintings are hasty while some are slow, some brown and muddy while others are vibrant and colorful, some hint at form and landscape, regardless of the artist’s original location.

The exhibition seems to dispel the binary simplification of East vs. West by putting artworks from New York and the Bay Area side by side. The only real and unambiguous distinction the curators made were between the abstract and figurative works.

In the end, I found that the most rewarding way of processing this exhibition was to enjoy the works one at a time, without necessarily racking my brain to link or dissociate the artworks from one another. Hackett-Freedman displays a large number of important names without overlapping them, providing a generalized survey which makes it difficult to draw strong connections between the artworks. I know that it would be naï ve to simply ignore the commonalities among artists of a particular period or geographical region; few artists would state that they create work in a vacuum free from any community, outside influences, or culture. However, it’s quite possible that the rapid globalization we experience today also existed in the 1950s and 1960s, creating an extensive dialogue between abstract artists in both locations. Or perhaps this conclusion simply depends upon what works and artists were available at the time of the exhibition’s curation.

When walking through the gallery, I began to think about how these issues play into the contemporary geographic distinctions. In Gordon Winiemko’s essay “Sampling What?”, he explores the connotations of segregating and defining contemporary artists in a similar way, specifically as in the recent “Sampling Oakland” show at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts. When I first moved to San Francisco, the San Francisco art community seemed close-knit to the point of homogeneity. The Mission School style, pioneered by Barry McGee, Margaret Kilgallen and others, maintains its influence on the illustrative, “low-brow,”, street-influenced style championed by the magazine Juxtapoz and the Web site fecalface.com. It is easy to be blinded by this seeming monopolization of San Francisco’s visual culture. But at the same time, just as in the Hackett-Freedman exhibitions, should all the work produced by San Francisco artists of this time were displayed on a wall of infinite proportions, side by side work from New York City, I hope I would be surprised by its diversity and find myself unable, in most cases, to guess where the artist came from.

Hackett-Freedman Gallery