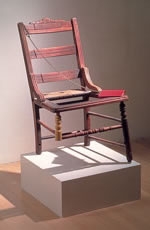

Three-Legged Chair (1978), David Ireland, Wood chair, journal, and metal chain; Courtesy of the artist; Gallery Paule Anglim, San Francisco; Christopher Grimes Gallery, Santa Monica, California; and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York [photo credit:] schoppleinstudio.com

Feature: Reviews

D.I. I.D.: Two Books on David Ireland

The Way Things Are: The Art of David Ireland

Karen Tsujimoto and Jennifer R. Gross, Ahmanson Murphy Fine Arts with the Oakland Museum of California, 2004

Touching Time and Space: A Portrait of David Ireland

Betty Klausner, Charta Books, Milan and San Francisco Art Institute, San Francisco, 2003

Jennifer R. Gross opens “Consider the Object as Evidence,” her essay in The Way Things Are: The Art of David Ireland, with an extended riff on a work of Ireland’s called Three-Legged Chair (1978). The form of Three-Legged Chair is as advertised, an amputee dining chair, minus a seat and plus a little red book chained to the back. This volume recounts two stories, “parallel narratives about things that are missing a leg,” as Gross puts it. Both stories are told in the first person, both are stories from Ireland’s life. Story number one recounts Ireland’s unsuccessful attempt to get the chair’s previous owner to tell him how it lost its leg. Story number two tells of his visit to an African village with the charming practice of amputating the legs of puppies so that they could not run away. Gross points out that the first story involved research and the second a quest, saying “both endeavors were actually hunts for meaning; both failed to bag their quarry.” Both stories relate to the work, yet neither explains it.

That about sums up the experience of reading, in tandem, two recently published books on Ireland. Touching Time and Space, with its “portrait” subtitle, has more material about Ireland’s life. Klausner, drawing on scores of interviews with Ireland’s colleagues, friends, and family members, devotes fourteen pages and three chapters to his childhood, which Tsujimoto covers in one page. The Way Things Are, on the other hand, offers deeper art historical context. For example, Tsujimoto offers a substantial discussion of the affinity between the works of Ireland and Marcel Broodthaers, a reading based in her own understanding of the works rather than Ireland’s own interest in Broodthaers.

Usually one would expect to find the most illuminating comments on an artist’s work in a catalog for a retrospective exhibition, rather than in a biography. Despite their popular appeal, gossipy biographies such as Naifeh and Smith’s Jackson Pollock: An American Saga offer only sidebars to the art and may actually obscure the qualities that make the art endure. But in the case of Ireland, who has spent many years making art so close to life that it can be hard to tell the difference, a biography could give a catalog a run for the meaning. In any case, Ireland’s work is rich enough that time devoted to reading multiple views of his art/life complex is worthwhile.

In a few instances, Tsujimoto, Gross, and Klausner all discuss the same topic to somewhat different ends. Here’s their chorus of voices in regard to one of Ireland’s most famous objects, the Broom Collection with Boom from his artwork/house at 500 Capp Street in San Francisco.

Tsujimoto: “Arranged from the least to the most worn broom, and then back again, the work is symbolic of a social tool used for cleanliness. More important for the artist, it is a visual metaphor for the passage of time: a broom is purchased, used until it is worn down, and then a new broom is purchased, and the cycle continues.”

Gross: “These worn tools are relics of Mr. Greub’s labor; by reconfiguring them in a circle, Ireland turned them into a timepiece that marks the sum of incidental time and effort expended to make the house a habitation.”

Klausner: “Broom Collection with Boom, like 500 Capp, questions the American belief in consumerism, in our lust for more and new… I find myself reflecting on what disposable means and how much our culture is dedicated to cleaning up, throwing out, and acquiring the latest model. “

Both volumes are well-illustrated and handsomely designed; however, Klausner’s editor did her no service. While Klausner is an excellent interviewer and offers first-hand accounts that will no doubt be mined by future art historians, there is a consistent and annoying zig-zag in the way information is presented. For example, when Ann Hatch, an important patron of Ireland’s, first appears we are told that the back of her car is filled with apples. This intriguing but seemingly random detail is not contextualized until several pages later, when it develops that she keeps an orchard. Eventually I got used to flipping back and forth between chapters to put information together—it is a tribute to Klausner’s excellent material that I was willing to expend the effort. It could be argued that the book is simply arranged according to different priorities than my own, but there are no arguments to justify the misspelling of Jackson Pollock’s name as “Pollack,” one of several editorial missteps in the spelling of artists’ names.

What really matters, though, is that these two books together go a long way to connecting the reader with the largesse of spirit that animates Ireland’s work. Because of its modesty and strong element of site-specificity, his ouvre has been difficult to get acquainted with. If you weren’t around when works were shown—say, because you weren’t born yet or because you lived in Butte—until the publication of these books there wasn’t much to go on. In a ruminative moment Ireland told Klausner, “If you want to be an artist and you want to function in the art culture, the challenge is to see how closely you can stay to real time/space without becoming invisible. I would love the notion that whatever I do would become virtually invisible as an artwork. But you can make yourself so obscure that you don’t exist.”

Touching Time and Space and The Way Things Are do an excellent job of making Ireland and his works visible, bringing them into existence for new readers.