Feature: Reviews

Documenta 11

- Kassel, Germany

- June 8 - September 15, 2002

It took five years to create this year’s especially process-heavy installment of Documenta, the international art event held in Kassel every five years. Four symposia-like meetings, or “platforms” - one per year - were held on weighty topics like truth and reconciliation commissions or “democracy unrealized” to determine the “constitutive conceptual dimension” of the exhibition. I had naively hoped that from these meetings new approaches and new kinds of conceptual, social/political art might emerge.

Instead, Chief Curator Okwui Enwezor and his team of curators focused on stale, heavy-handed reworkings of ideas hatched during the 1980s and 90s. Rather than filling the four gigantic exhibition halls with “stickier” approaches to delivering “information bombs,” the overwhelming majority of works on view depended on mind-numbing reams of didactic panels and supporting paperwork, pummeling the viewer with text-based messages. It wasn’t long before I felt my eyes glazing over, submerged in the curse of our times, too much information. Groups like Park Fiction, Raqs Media Collective, and Fareed Armaly (who, with Rashid Masharawi and Sylvie Fouet, created an especially text-heavy work about the Palestinian diaspora) delivered pieces so unmanageable and uninviting that their important and well-researched messages were lost on me.

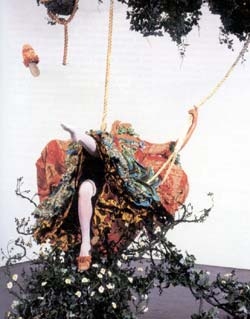

A handful of works did deliver. In Maria Eichhorn Public Limited Company (2002), Maria Eichhorn succinctly displayed evidence of the process of creating an actual corporation through which she moved 50,000 Euro - then dead-ended the circulation process by putting the money on display in the show. Yinka Shonibare’s installation Gallantry and Criminal Conversation (2002) featured tableaux of figures dressed in 17th-century costumes made of African print fabrics arranged in pornographic poses. The work packed an instantaneous punch and left you reeling with layers of implications. The Atlas Group employed a trickster approach, showing documents from their “archives” about unrest and civil war in the Middle East and Lebanon, which were believable enough to leave the viewer guessing at their veracity. Multiplicity’s multimedia work Solid Sea (2002) intriguingly recast the Mediterranean as a rich and dangerous world unto itself, loaded with lore and social/cultural perspectives. And in Disappearing Element/Disappeared Element (Imminent Past) (2002), Cieldo Meireles set uniformed ice-popsicle vendors at each exhibition space to make a larger statement about ownership and distribution of essential resources like water.

Culture vulturing

Many artists and groups in the show created works that dabbled at anthropology or social work. This trend gained prevalence (in the U.S. anyway) during the crisis in arts funding of the early 1990s, when framing art practice as an educational or social service function was a way to justify art’s usefulness to funding agencies. Artists and groups like Ravi Agarwal, Igloolik Isuma Productions, and le Groupe Amos create and distribute visuals in the art context that are a byproduct of ongoing social-work-based projects they do with “disenfranchised” or “at-risk” populations within their own cultures or simply to “interpret” such a culture to a Western educated audience. The question arises yet again - why not show pictures and ephemera created by groups that are trained in the field of anthropology or social work? Practitioners in those disciplines are better qualified to do such work and are schooled to consider the problems of their position in relation to the populations with which they work.

The illusion of impartiality some artists and filmmakers assume is disturbingly naive, touristic, or romanticized. Some, like Trinh Minh Ha and Ulricke Ottinger, seemed merely to point the camera at the exotic “other” without examining their own role in the relationship - as though the camera made them somehow neutral or invisible. Worse, the relativistic brand of multiculturalism that underpinned this significant conceptual thread in Documenta 11 now seems dangerously out of step since 9-11. The pure and simple fan tribute of Pierre Huyghe’s video on the origins of scratching and hip-hop seemed to me a more legitimate position to assume. Insightful photojournalistic works on apartheid South Africa by David Goldblatt also delivered a potent political punch.

The importance of good hospitality

The exhibition highlighted a bothersome trend of video “installations” that were darkened rooms playing one video on a wall - not an installation by any stretch of imagination. Many lasted from thirty minutes to over two hours, often without seating. I found myself lingering in some spaces more because there was a place to sit down than because the work was intriguing. Perhaps the exhibition could have been dotted with screening rooms with good seating and schedules posted, so that one could duck in and watch a video or two of interest. Artist and viewer were both shortchanged; viewers, tired of standing, moved on after staying only a few minutes with each piece. Two outstanding video installations were similar works by Isaac Julien and Eija-Lisa Ahtila. Both used autobiographical narrative as a point of departure to surreal mentalscapes. Lush and well-crafted, each employed a synchronized three-screen format.

To reveal or obscure

Installation is a lingua franca of international art shows, and Documenta 11 was no exception; on view were big, expensive installation works by Mona Hatoum, Chohdreh Feyzdjou, Victor Grippo, Artur Barrio, and Mark Manders. How ironic that what began as an anticommodity art movement has become the art market’s version of crowd-pleasing, Hollywood-style cinematic spectacle. Two standouts both utilized as their primary element the ultimate intangible, light. In Untitled (Kassel) (2002), a succinct performance/installation by Tania Bruguera, the viewer enters a two-tiered, pitch-black space and hears marching footsteps and the cocking of rifles, then is suddenly blinded by thirty seconds of bright white light and absolute silence. The sequence is repeated, to chilling effect. Alfredo Jaar was one of a group of established artists selected whose work has had a profound influence on later generations in the show. In his installation Lament of the Images (2002), Jaar presented two rooms; in the first, text wall panels delivered information and statistics about monopoly ownership of images. The second room stood empty except for bright white light, which may be the perfect metaphor for our times. Light can either reveal or obscure, illuminate or blind. Perhaps what is needed most now is a cultural apparatus by which creators and curators can respond with light’s speed, so as to reveal rather than obscure.