Feature: Essays

Expó-see: A Memoir

[Editors’ Note]This article is the first in an occasional series in which Stretcher authors reflect on the art press: its history, its role in the creative community, and its successes and failures. Mark Van Proyen’s first-person account of the life and death of an artzine brings up many of the questions that the series will address as it continues: what constitutes significant criticism? what kinds of journalism are useful to a creative community? and how can a meaningful art press be sustained?

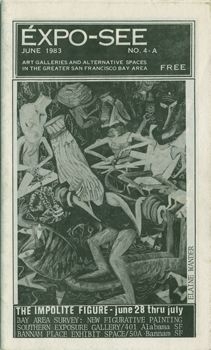

In the early months of 1983, artist and curator Rolando Castéllon started Expó-See magazine: a small, photocopied, eight-page pamphlet that initially functioned as an advertising instrument for Bannam Place Exhibition Space, the underground gallery he started in 1983. The gallery was literally underground, located in the basement of the building where Don Soker had his above-ground gallery in North Beach.

Rolando had been an associate curator at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, but in 1981 he was “let go” because the museum was becoming part-and-parcel of what was then called “The Manhattanization of San Francisco.” After that point in time, few big shows of local artists were organized, and the situation seemed ripe for some DIY hijinks.

As a project of Bannam Place Exhibition Space, in the summer of 1983 Rolando and I organized a big exhibition of new figurative painting titled “The Impolite Figure,” which showed the work of twenty-eight artists at the Space and the Southern Exposure Gallery. During that year, Expó-See reprinted two essays by Michael Peppe (originally published in the LA-based High Performance magazine); the first was titled “Why Performance Art is So Bad” and it was soon followed by “Why Our Art is So Bad.” These essays were and still are nothing less than unalloyed masterpieces of art criticism, the kind of things that nobody writes anymore for fear of what it might mean to tell the truth about the art world of expectations diminished by programmatic sensitivity and nurturant-personhood. Now, what passes for criticism is all “educational explanation,” which is sycophantic cheerleading called by another name. Tedious, very tedious. In a saner world, Michael would be widely recognized as a living cultural treasure, at the very least, a treasure-trove of inspirational quotability: For example, from the former essay we read: “...what can be done about the rest of this halitotic idiom, this Thalidomide Muse with neither eyes nor ears but only a gigantic sucking mouth? Easy. Ignore it. Go to a movie, read a book, attend a concert, dance. Without witless, automatically-clapping audiences like ourselves to feed on, performance art faces the same choice we do: mutate or die.”

Those essays set the tone for the moment when I inherited the pro-bono editorship of Expó-See in the Fall of 1983. Rolando was hired as the Director of the Mary Porter Sesnon Gallery at U.C. Santa Cruz, so he had to liquidate some aspects of his underground publishing empire. At that point, we separated from Bannam Place and became a project of the Friends of the Support Services for the Arts, which was an organization affiliated with the South of Market Cultural Center. The new production team consisted of Christa Malone, associate editor, Bill Roarty, production manager, and Armagh Castle, the designer. None of us made any money, but we did pay our writers, which is something of which I am still very proud. Cecile McCann, founding editor and publisher of Artweek, was very supportive with advice, practical information and encouragement. Soon we were publishing three issues a year, and our little pamphlet grew into a small magazine of 48 pages, half of which were devoted to editorial content.

By the spring of 1984, we actually sold enough advertising to cover a press run of 1000 issues. This was funny, because we were publishing commentaries that often attacked the people who bought the ads. One of my own was titled “A Few of My Least Favorite Things,” which emptied both barrels on an art scene that had grown feeble on a diet of self-congratulation, petty cronyism and minimal financial support. This was published in the summer of 1984, at the time when San Francisco hosted the Democratic National Convention at the Moscone Center, an event that was memorable because it occasioned the naming of Geraldine Ferraro as the first woman to be nominated Vice-President of the United States. Those were the years when Punk was just starting to run out of gas, but Mark Pauline’s Survival Research Laboratories events were gaining momentum and recognition, and I still regret that Expó-See didn’t do an issue devoted to the work of that group. We had the opportunity.

Looking back, it now seems clear to me that our graphical and editorial tone was influenced by Vail’s punk fanzine, Search and Destroy, which ran from 1977 to 1980 and was very popular with the neo-bohemian gang who were students at the San Francisco Art Institute during those reckless years of wild shows at the Mabuhay Gardens. The first issues of his more widely circulated “Re-Search” books were contemporaneous with Expó-See, and they, too, shared the spirit of those times, those being the times of Ronald Reagan, which were times of fear.

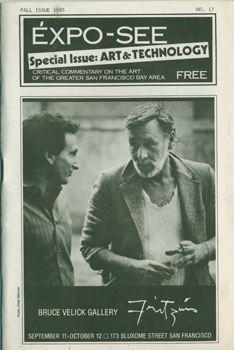

The best thing that Expó-See did was run long interviews with established artists such as Squeak Carnwath, Joan Brown, Fred Martin, Anna Halprin, Tom Marioni, Wally Hedrick and Bruce Conner. Those interviews had a tell-it-like-it-is candor to them, which is something else that you don’t see in today’s brave-new-world of blind faith in our own self-impersonations. In 1984 and 85, we also launched a collector’s frenzy for the work of an artist named Harry Fritzius, who Christopher French and I mischievously dubbed the “last real beatnik artist.” That was not true, since the Beat movement in San Francisco ended in about 1964, a full decade before Harry came out from New York City. But Harry’s winning personality had a way of hypnotizing people, and for a few years he became the toast of the town. Harry was a an old friend of San Francisco Chronicle art critic Thomas Albright (who died in 1984), and he lived and worked in an apartment on 19th avenue making paintings and collage objects that evoked a mythopoetic shadow world. Harry died in 1988, a self-destructive victim of his own sudden success.

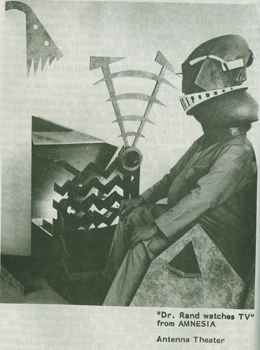

During those early years, Tony Reveaux was writing some very searching essays on technological innovation in the visual arts, so we invited him to guest edit an issue on art and technology in the Fall of 1985. That issue featured interviews with Antenna Theatre founder Chris Hardman and sound sculptor Bill Fontana, and their remarks proved to be prophetic of the wave of technologically-oriented art that would emerge in northern California a decade later. But that prophesy also signaled our demise, because we couldn’t interface with computer-driven changes in printing procedure, simply because none of us could afford a computer. After finishing our fourteenth issue, we bagged the whole thing in 1987, in large part because we were tired of working for free.

###

The age of art is over. Due to the democratization of education, the cheapness and availability of art technology, the increase in leisure time, the spread of literacy, the expansion of mass communication, the growth of population and the decentralization of art culture away from strictly urban areas, it is now possible for everyone to be an artist.

—Michael Peppe