Feature: Reviews

Jamie Brunson

- Katrina Traywick Gallery

- Berkeley

- Through November 30, 2002

Since 1998, Jamie Brunson has been working in a pattern-based format, borrowing motifs common to the architecture and decorative arts of many cultures that she has visited over the past two decades. In previous artist statements she has avowed lyricism and tactility, saying that she seeks to “evoke the kind of eroded beauty that natural forces enact on human artifacts over time.”

This series of paintings extends and refines traditional motifs in sophisticated ways, as Brunson adheres to her sensual response to her surroundings with the exalted state of awareness that comes with seeing new places. Brunson’s surfaces are densely saturated with color applied in an understated layering suggestive of fired glazes. The layers may reveal partially obscured patterns or be altogether dominated by them. With pattern-based art there is no content as such, but rather the formal repetition of motifs arrived at collectively and generationally. This approach would seem to eradicate the notion of individual expression. Yet within the march of tradition, the sensibilities of certain individuals stand out even as they remain anonymous. Paradoxically, Brunson submerges herself in tradition en route to distinctive visual variants on it.

This devotional approach to art-making is also informed by Brunson’s formalist tendencies. The work is both a channel for spiritual states that defy interpretation yet exert an expressive imperative, and a repository of the memory of specific places and experiences, conveyed in an understated register that beguiles the eye with simplicity and rewards prolonged looking with a host of visual stimulants. In a painting like Chandra, for example, there is the repetition of arabesques hovering between filigree and script, alternately blurring and coming into focus in a matrix of Egyptian blue, as if the artist’s task had been to transcribe an elusive palimpsest of signs.

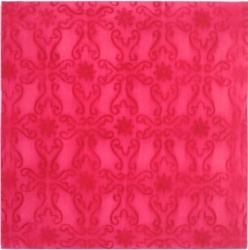

Victoria, a lattice of faint blue enshrouded in a mauve ground, is like a barrier that might yield to an unlimited sense of spaciousness when approached, whereas with Intertwining Blossoms one is confronted with a dense, somewhat off-register vegetative screen, wine-dark, as close and enveloping as a reverie. Vegetative patterning is also present in Cuilapam, its name evocative of ancient Mexico, with a Moorish decorative motif abruptly giving way to a series of vertical totemic columns that appear to be branded on a background of wood.

Las Flores is perhaps the most strikingly formal painting of the show, with austere rows of purple Chinese symbols hovering in relief before a shadowy grillwork like the crests of powerful guardian figures. Brunson exploits the grill or latticework motif here and in past works to powerful effect. It is an optical given that armature and interstice maintain a visual embrace that is either static or dynamic, depending where one’s attention falls. There is a constant tension between grillwork and empty space, near and far, pattern and ground, yet because of the attention to surface, one is kept in mind of the artifice that set the process in motion. The combination of these visual forces opens up a meditative moment for the attentive viewer, and if one allows that moment to prolong itself, just as the latticework of the pattern at hand extends beyond the pictorial frame and in every direction, one has made a fruitful beginning. It is possible to read the “subject” of these paintings as no less than the abstracted invocation of the divine in Islamic art, or as what the critic Irwin Panofsky has referred to as the “two infinites,” the infinitesimally small and the infinitely large, in the paintings of early Netherlandish masters like Jan van Eyck. This is not to say that one is bound to a concept of divinity in Brunson’s art, indeed there is no such indication, but there is a sense of interconnectivity, of containment and letting go that goes beyond the casual.

Even Brunson’s formal structures are subject to double entendre. One expects from the grid or lattice a kind of unyielding regularity, a metonymic opacity that forces the viewer back on himself. This might be the case had the grids or lattices themselves not been finely individuated by the painter’s hand, had the grounds not been worked over with a hidden aggression that is so thoroughly integrated and effaced that they pretend to stand in more as vanished presences than as the struggle of an individual. The result of this dedication and its muted presentation is riveting.

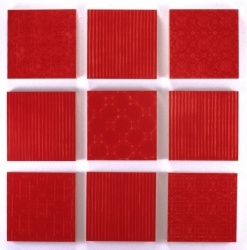

This show marks a shift in Brunson’s palette toward vibrant, even piercing, color. In her work, hues of this intensity are typically associated with feelings of passion, joy, and spiritual transcendence, and paintings in which patterns or grids merge with reciprocal color fields rather than evoking a dynamic of containment/release. Psychedelic Paisley Study is a good example of this head-on engagement, or the blood-red Chamundi, a series of small, square compositions in a grid in which color and form are almost equally weighted. This reciprocity is carried a step further in Attarine, where an array of pitchfork tines glow barely perceptible in a furnace of fire-orange, or in Shimmer, in which the effect of interlacing yellow helixes dissolving into brighter valuations is mesmerizing. Other works, such as the lovely Marigold Study, a floral motif in yellow on a deep saffron ground, produce a vibrating optimality.

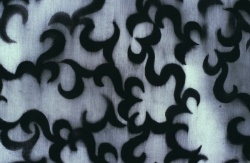

Paintings that stand apart from the rest and that might be indicative of further new directions for Brunson are Tangle and Sura. Tangle is a Brice Marden-like net of green strands receding into a background of echoing forms. Unlike Marden’s work, however, there is an emphasis on depth and a containing medium, also green, that gives these forms an entwined plasticity, like suspended strands of seaweed. Sura, one of the largest works on display, is a monochromatic study of hooked and pronged forms that suggest the swirling, descending restlessness of storms.

Jamie Brunson: New Paintings is a strong showing from a painter whose sensibilities and methods are finely attuned and whose star, I believe, will continue to rise.

For more information, visit Katrina Traywick Gallery.