Feature: Reviews

John Bankston Talks

- Rena Bransten Gallery

- San Francisco

Pirates, Cowboys, Fantasies

An interview in conjunction with

Bankston’s exhibition at Rena Bransten Gallery

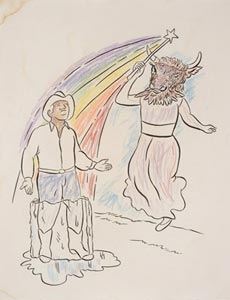

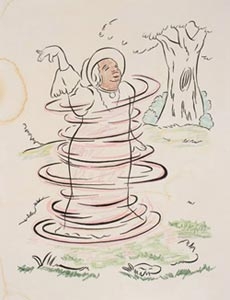

San Francisco-based artist John Bankston pulls you into a fantasy world and leaves you to find your own way back to the gallery. Using the visual language and non-linear narrative of a coloring book, Bankston allows the viewer to toy with fantasies, switch identities, play dress up, and ride off into the rainbow. His images combine black line drawings with colored abstraction, zapping the viewer with a tinge of eroticism.

Bankston received his MFA in painting from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. In addition to receiving the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s SECA Award and Joan Mitchell Foundation Grant (both in 2002), Bankston has been included in several collections including the Studio Museum in Harlem and the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Harford, Connecticut. On the heels of his exhibition Wild West at Rena Bransten Gallery in San Francisco, I sat down with Bankston to ask him some questions about role-playing and his fantasy world.

Bruce King-Shey: How much power do we really have to color our own identities?

John Bankston: Well, I think it relates back to painting or art. Much of it is about the viewer’s reception. I can decide I am going to be a pirate today and wear my pirate outfit. But I don’t necessarily know how you as an observer would perceive that. I don’t know if you would even think of me as being a pirate. The power is always kept in check between reception and what is put out.

BKS: It’s the contrast between what you are trying to be and what people are willing to accept.

JB: Exactly, yeah. It’s not like the person who is dressing has all the power, because it’s also about how it’s interpreted.

BKS: Then what is the difference between reception and being forced to play a certain role?

JB: I guess we are always forced into some kind of role. But I don’t know if we necessarily accept it. You are always going to be seen a certain way. It’s like when I go home. I am not the same person I was when I left. I think it is up to the person who’s putting you in the box to see if you still fit or not. Sometimes you’re in a situation where you have to be a certain way. It’s not that you necessarily change; it’s just that you adjust to the dynamics of the situation.

BKS: Given the narrative aspect of your work, how do you feel about your paintings being separated?

JB: I actually like the idea of them being a unit that gets separated. It’s like an album and a single from that album. All together it makes a work, but it can live on its own, too. Coloring books are not really linear; they jump from one image to the next. You can understand them as a story or you can see them as individual pages.

BKS: When they go with different people, it’s like separating puppies.

JB: But then it’s this thing that unites different people so everybody has a part of this puzzle.

BKS: Would you talk a little bit about your personal history and how this is reflected in what you are presenting in your art?

JB: It’s personal in that it comes from me, but the stories don’t have really anything to do with my personal life. I don’t know where the stories come from really. Part of it is that they are fairy tales or common stories that we know in some way. They start from that but I don’t think they are autobiographical.

BKS: Maybe not necessarily the stories, but what about the issues surrounding race, sexuality or identity that you put forth in your work?

JB: Well, I guess I don’t feel like that is part of — I mean it is definitely a conscious thing — but I guess I have never really thought about it as autobiographical. I am imaging a world where most of the characters are black and they all exist within this gay sensibility. It’s those two things that set the cultural standard for this world that you encounter. Because neither of those is the cultural norm of the world that we live in, I don’t think of it as autobiographical.

BKS: It has been said that you art deals with “mature” subject matters or deals with sex and race. If everyone in the world was gay, or gay and black (or maybe a gay black cowboy!), how differently do you think your work would be interpreted?

JB: I think it is interesting that people feel it is really mature. I like that because there is nothing explicit in the work. I think a lot of it goes on in the viewer’s mind. And maybe that makes people uncomfortable — entering into this fantasy and situations that they wouldn’t necessary think about. I actually like that it makes people uncomfortable because how many times do people think of someone who dresses in leather and try to see the world from that perspective? Temporarily they have to step outside of who they are if they want to get the story. Because the work suggests a narrative and because the narrative jumps, the viewer has to fill in the gaps and enter into the character’s shoes and think things they might not necessarily think or might even be uncomfortable thinking about. It’s like stepping into the shoes of an “other.”

|

|

BKS: Tell me about the mixing of the erotic overtones with a completely non-sexual coloring book form.

JB: I was trying to combine the visual experiences of being in San Francisco, seeing different people and hearing all kinds of stories. Though I was interested in the idea of narrative, I really didn’t feel like I had any stories. I thought: this is a way for me to start. So I feel like the work is about this other place where it’s very… it’s sort of sexually charged but only because people are able to explore their fantasies. In a way, it’s like San Francisco, where this idea of fantasy and dressing up seems to be so much part of the city’s culture. It comes from trying to process things I see everyday on the street, wanting to have a narrative, in this other place where cultural norms are how we experience them here.

BKS: We live in a different world in this city and we just don’t realize how lucky we are.

JB: It is a different place. There are so many characters, and it is just so much about invention and inventing images.

BKS: So what is it about gay men and their identities? What is the difference between being a straight man and a gay man?

JB: They are the same but they are opposite in a way. I see straight men very consciously cultivating their straight images. Our culture is so geared toward this macho, male persona that anything contrary to that is a shock. But there are gay men who also want to play the macho male.

BKS: Oh, yeah, there are…

JB: I don’t really see straight men exploring their more feminine or softer sides. I think that gay men are more fluid in terms of exploring various identities or roles.

BKS: How is this for a role: as a prominent black and gay artist, do you embrace the role of a figure in issues regarding masculinity, ethnicity, and sexuality?

JB: I don’t think about it. I hope my work is participating in a discussion about masculinity and race, but I don’t want it seen as a theoretical exercise about that. I want it to be a visual experience first. I hope it’s not something where someone will say: that’s not about me, so I don’t have to look at it or think about it. Coloring books and the fairy tales are part of our shared culture. These are things we all have experience with and unify us all. But it is in going through the work’s narrative that difference becomes apparent. You are able to accept it or it makes you feel uncomfortable. But you are still going through it, so it’s not like you are saying: it’s not about me, so I am not going to look at it.

BKS: So do you believe in the riding off into the rainbow? Do you believe in marriage? Or is that part of the fairy tale?

JB: Riding off into the rainbow? I think being in San Francisco you are in the rainbow. Marriage. If you find someone you want to spend forever with, that’s good. I am interested in this idea of straight and gay culture mirroring each other, in this funny way on these parallel paths. I am not exactly sure what to think of it, but maybe through the work I can play with the idea.