Feature: Reviews

Modern Cartoonist: The Art Of Daniel Clowes

- The Oakland Museum of California

- April 14 - August 12, 2012

The late Robert Hughes once remarked that "The museum has very largely supplanted the church as the emblematic focus of the American city." In Oakland, that would be The Oakland Museum of California, a museum that billed itself in 1969 as a “museum for the people.” In 2010, it opened the doors to its extensively renovated permanent galleries as well as debuting an expanded section that consisted of two medium sized rooms meant for rotating exhibitions. In my review of the opening show of their re-imagined art galleries for Art Practical, I found that the increased focus on education – mainly through interactive exhibits – didn't completely work and served up a platter of distractions from serious consideration of the art on display. It’s been over two years since my evaluation of the museum's art galleries. Where do they stand now?

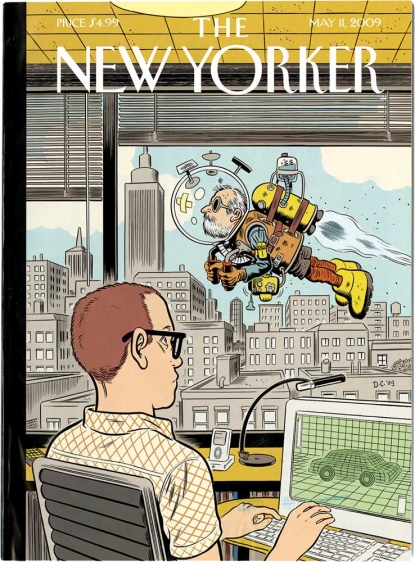

Modern Cartoonist: The Art Of Daniel Clowes, the museum's latest major art exhibition, is a natural fit for the museum and is their most successful effort at redefining and perhaps, expanding just what an exhibition can be. As co-organizer René de Guzman said in the press preview “As we like to think of our institution as the “people's museum,” I think that comic books are the “people's art.” The artist in this case is Oakland-based and many of the scenes depicted are local as well. His movies and comics as well as New Yorker cover illustrations have received wide acclaim. This show is a natural fit and does a good job arguing that comics can be considered fine art worthy of serious attention.

In contrast to the OMCA's show with Mark Dion, The Marvelous Museum, this show’s approach to interactivity and immersion is intuitive and not the least bit distracting from the works on display and the larger themes they aim to evoke. This was aided by the innovative and rather unusual exhibition design by Nicholas de Monchaux. Many of the works were shown on sliding display cases outfitted with multiple sliding walls, allowing the viewer in a sense to “curate” their own personal experience. It proved for me, to be an effective way to ignore the space’s relative smallness allowing for the show to feel major. It was engaging without sacrificing the show’s overall seriousness.

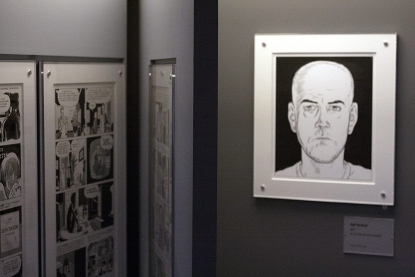

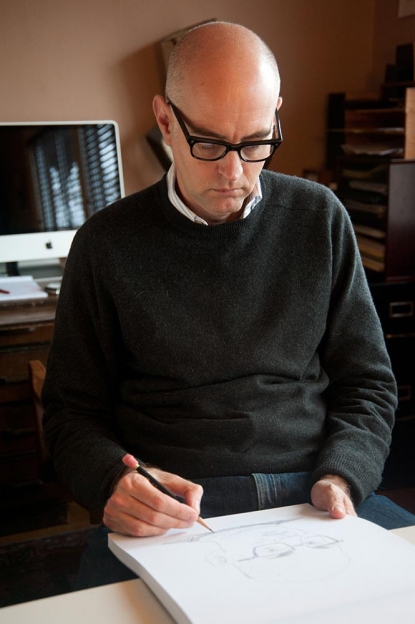

Of these works presented, lies one of the most effective: a 2011 black ink on white board self portrait of the artist. In it he looks like his version of his personal beau ideal: namely reserved yet bold, private yet candid, and harsh yet tender. The lines of his face are well drawn; that of a soccer dad who has lived a life uncommon to his fellow parents watching the kids score goals. But, they are of an ideal, somehow less awkward in their surefooted crafting than in the reality of life, much like the cinematic manipulations of comic books and the films Clowes has a large hand in creating. The intended interactively is most acutely seen in a somewhat subdued fashion. Sketchbooks were placed on tables in the exhibition room and patrons were encouraged to add their responses in drawing form. In one, I spotted what was very likely, a Clowes sketch. Blurring the barriers in evidence, I imagine.

On a personal level, this is not an easy show for me to review as I have been – on and off – a fan of Clowes' work since I was in high school. His recent work has often struck too formal a note and left me a bit cold. The most recent film version of his work “art school confidential” turned a fantastic critique of academia into a rote joke, beaten dead horse style until it could wring no more wit, bloody, sweaty, or otherwise from its caffeinated grip. The influence of Chris Ware, another prominent comic artist hangs heavy over this show, as his obsessive formalism has deeply influenced Clowes’ most recent work; particularly his recent graphic novel Wilson. In it,wild stylistic shifts occur from chapter to chapter – one evokes the work of Peanuts creator Charles M. Schulz and another conjures up portraiture.

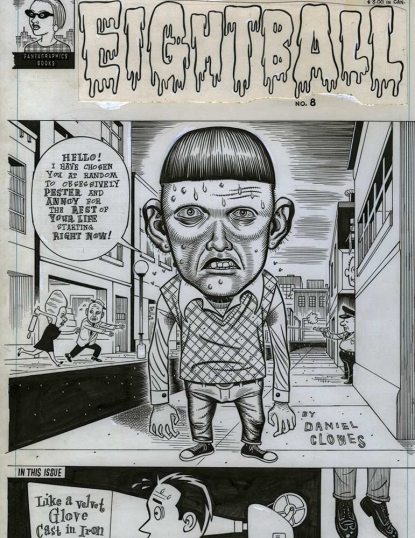

Clowes’ earlier works in his comic series Eightball and in Cracked magazine belie the sense of an illustrator shaking off the then popular fashion of propulsively sarcastic adherence to the tradition of Mad magazine’s Harvey Kurztman. With this most recent work, he has succeeded in a fashion greater than Ware to marry graphical codes; shifting to a nuanced understanding of the tragicomedy found in everyday human life.

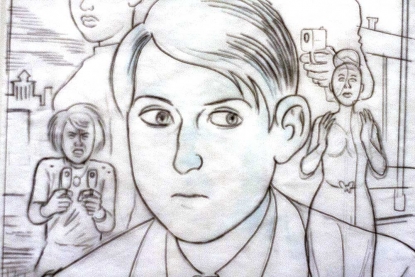

Clowes’ Mr.Wonderful strip series originally presented in the New York Times is perhaps the most successful of his endeavors towards a more nuanced and more personal take on the human condition. In it, a schlub is on a date with a moderately attractive woman who is having a conversation with the title character. The thought bubbles of the strip overwhelm and demolish the words of his date signifying self regard and egotistic overreach. The bubbles read: “Most beautiful women turn so bitter when realities of aging set in. Hard to blame them. I suppose. It must be kind of awful.”

Clowes' best work is Maileresque in its astringent complicity with narrative. It must be noted that something is added and yet subtracted when taken out of the context of the comic panel and the comic book itself.

The show is hung and organized in an innovative manner and much credit should be given to its curator Susan Miller. A selection of Clowes' Eightball comic series is under glass. His panels and sketches are mostly chronologically placed and others are in sliding walls making a strong argument for a serious appraisal or reappraisal of the work.

This exhibition has made abundantly clear that the OMCA can be a place where the lines between the low, middle and high brows can be blurred to produce eloquent discourse. In America, the middlebrow is all too often mislabeled as high and we are found wanting for the false advertisement. In Modern Cartoonist: The Art Of Daniel Clowes, a case is made for the lowbrow working as high art; speaking dryly and wryly to the impoverished social state of human interaction in the modern world.

Home page image - Eightball No. 18 Cover, Daniel Clowes