The Silence (1973), Joseph Beuys, Five reels of 35 mm film, galvanized, 26.3 x 38 x 38 cm. Harvard University Art Museums, Busch-Reisinger Museum, The Willy and Charlotte Reber Collection, Edmee Busch Greenough Fund, 1995.280. Photo: Photographic Services. Copyright President and Fellows of Harvard College.

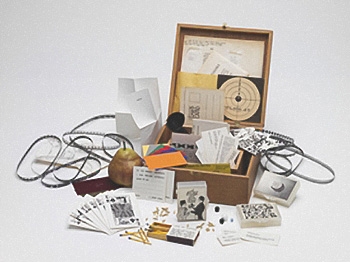

Flux Year Box 2 (c. late 1960s),Various Artists (George Maciunas, editor and designer), Wooden box with title screen-printed on lid, containing numerous Fluxus editions, 20 x 20 x 8.5 cm. Harvard University Art Museums, Fogg Art Museum, Barbara and Peter Moore Fluxus Collection, Margaret Fisher Fund and gift of Barbara Moore/Bound & Unbound, M26448. Photo: Photographic Services. Copyright President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Flux Clock (Distance Traveled in mm (c. 1969), Per Kirkeby, Modified alarm clock with printed paper face, 6.9 x 6.9 x 3 cm. Harvard University Art Museums, Fogg Art Museum, Barbara and Peter Moore Fluxus Collection, Margaret Fisher Fund and gift of Barbara Moore/Bound – Unbound, M26421. Photo: Photographic Services, © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Feature: Reviews

Notes on Art and Life at Harvard

- Busch Reisinger Museum

- Cambridge, MA

- February 24 - June 10, 2007

Our Common Humanity – Multiple Strategies

The unique opportunity to hear Bill Clinton and Bill Gates speak, one day apart, occurred during this year’s graduation week at Harvard University. Though it initially seemed an odd pairing, it was valuable to be reminded that both of these remarkably intelligent and creative thinkers are deeply involved with issues concerning our common humanity. President Clinton spoke of the almost identical genetic composition of all people, as a means to encourage the graduating class to cultivate a humanistic world view as they plan their post-college futures. Mr. Gates addressed the overwhelming task of caring about the welfare of others in our complex world, yet exhorted each graduate to take on a human problem as one small focal point in their lives. Both of these men are fine motivational speakers, and their words were inspiring and timely.

While in Cambridge I visited the Busch Reisinger Museum, where I had the fortune to see Multiple Strategies: Beuys, Maciunas, Fluxus. Striking was the affinity between the social imperatives expressed by the Harvard graduation speakers, and those inherent in the works of these artists. This is particularly germane to Joseph Beuys’s Actions and objects, but also apparent in the work of George Maciunas and various Fluxus artists through their inventive creation of multiples during the 1950s and 60s. Beuys’s philosophies were especially well expressed in this context, with such projects as his Kunst=Kapital (Creativity=Capital) screen prints, and Wirtschaftswerte (Economic Values) (1977-83)—basic consumer goods manufactured in E. Germany—that strongly state his belief that only through art could a new economic and spiritual order be constructed and sustained. I was inspired by photographs of Beuys’s Organization for Direct Democracy Through Referendum, an information office he crafted for documenta 5 (1972), where he discussed goals of the organization with visitors. The well-known symbol of this Action included here—Rose for Direct Democracy, a fresh red rose in a graduated cylinder, intended to signify the union of art and science—has great resonance today. Images and objects from Beuys’s Hundred Days of the Free International University, which were part of Honeypump in the Workplace at documenta 6 (1977)— an enormous network of plastic tubing, lubricated with 200 pounds of margarine, through which honey flowed—concretize the circulation of energy and ideas Beuys generated through lectures, workshops, and discussions.

Allusions to the possibility and impossibility of communication, so central to Beuys’s work, were also evident in the projects of George Maciunas and the Fluxus artists. However, a primary difference between Beuys and Fluxus artists was the issue of authorship and the ephemeral nature of Fluxus activities. It was enlightening to read Fluxus event scores and to consider images of some of these artists’ works, such as Takehisa Kosugi’s Theatre Music, performed at the Fluxhall in New York on April 17, 1964. For the performance, participants stood on an oversize ink pad at the Fluxhall entrance and walked across the paper covered floor, leaving their footprints, directed by Kosugi’s instructions to “keep walking intently.” Like Beuys, Kosugi and other Fluxus artists wanted to apply to daily life the level of attentiveness normally reserved for art, though their goal was not to produce ‚Äòart.’ This intention and distinction was well represented in the exhibition by the inclusion of various Fluxus editions. For some of these, the artists used absurdist objects to parody artwork’s status as nonfunctional commodities, demonstrating how the marketing of ersatz commodities under the Fluxus name (eg, Claes Oldenburg’s False Food Selection (1966) and Robert Watts’s Flux Rock Marked by Volume in CC (1964) allowed Maciunas to upend the concept of branding.

One significant legacy of this exhibition was the inclusion of manifestos. Among them was Joseph Beuys’s 1970 alteration of George Maciunas’s 1962 manifesto. For Maciunas’s stated rejection of “Europanism” [sic] as elitist and imperialist, Beuys substituted “Americanism,” signifying his identification with the longer tradition of European culture, clearly evident in Beuys’s multiples that pay homage to personages ranging from Leonardo da Vinci to James Joyce. Various Maciunas/Fluxus manifestos were on display, augmenting the various ways in which Beuys’s and Maciunas’s challenges to aesthetic categories had impact on the way art was exhibited and distributed. Though not officially a manifesto, one of the most fascinating works related to this genre was Maciunas’s Diagram of Historical Development of Fluxus and Other Four Directional, Aural, Optic, Olfactory, Epithelial, and Tactile Art Forms (Incomplete) (1973). Though it was difficult to read this huge wall mounted scroll, the extensive lineages Maciunas visually mapped—like “Walt Disney Spectacles,” which extends from both “Church Procession” and “Versailles Super Multimedia Spectacles,” as well as from “Roman Circus” and “Medieval Fairs”—were both ingenious and humorous.

The curatorial juxtapositions of Beuys, Maciunas, and Fluxus, augmented by examples of works by and discussions of Marcel Duchamp and John Cage, conceptual art and social sculpture, provided much historical precedent and context for the contemporary focus on socially engaged art practices. The creative ways in which these artists communicated their consistent edict—that change is necessary and possible in the world and the art world—continues to offer this transformative promise to everyone through active participation in shaping their political future. The reverberation of this message was heightened by the July issue of Vanity Fair, with its special focus on Africa and edited by Bono, which I came upon in Logan airport while traveling home. From its set of twenty different covers featuring a sequential group of famous individuals from around the world, engaged in dialogue about African issues (and photographed by Annie Leibovitz), to the genetic mapping of the masthead, the message—that we can and must determine how to shape our collective future—was communicated everywhere, loud and clear.