Feature: Reviews

On Painting

In the September issue of Artforum, Michael Wilson weighs in on Jenny Holzer’s exhibition of silk-screen paintings, “Archive,” at Cheim & Read gallery in New York this spring:

The content of the selected documents is so chilling and the manner of their presentation so seductive…that the dissonance between obscene realism and formal elegance does threaten to soften the content’s necessary blow. The series’ aesthetic is so tight that it soon begins to feel airless — even, at worst, cynically programmatic.

Earlier in the same issue of Artforum, David Joselit* has this to say about Holzer’s exhibition:

Holzer’s most interesting works in this series are those whose deletions are so uncompromising that entire canvases are covered in blocks of black. Here information meets the monochrome…in a provocative dialectic of abstraction and discourse… Under these conditions of a withering or embattled public sphere, what role should art play? In Holzer’s redaction paintings, art is a site where hidden knowledge may be recovered and reinvigorated rhetorically — it was striking how many visitors to the gallery seemed to be reading the paintings as content.

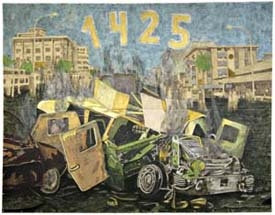

In July, Stretcher ran, in the East Coast blog, my comments on Holzer’s New York exhibition as well as, in the West Coast blog, my thoughts regarding RIGO’s exhibition in San Francisco. Because we are protected by physical space and time from the exigencies of New York art discourse, RIGO’s exhibition will not be given quite the intense scrutiny of Holzer’s exhibition. However, paintings with political subjects are most often dismissed as topical, especially by formalist critics. This has the unfortunate effect of killing the patient by amputating one of its limbs.

On the other hand, Kenneth Baker recently wrote that it is difficult, in the face of our present political circumstance, for abstract painters to maintain their practice. This is another misunderstanding of where painting comes from, how it arises, what it signifies and the many “purposes” it serves.

This summer, I not only saw Holzer and RIGO, but at the Legion of Honor, San Francisco, I saw Monet’s Wisteria, 1920, predating Joan Mitchell’s wristy action calligraphic stroke by thirty years. Casual, loose, unfinished, Monet brushed wisteria into being on a bare canvas ground, branches, cone shaped flowers, olive-greens, browns, blacks and Naples yellow.

At the San Francisco Art Institute, I saw Kehinde Wiley, an alumni, in the Faculty/Alumni Exhibition. Combining old-masterish civic group portraiture with pattern and decoration and full of ‘tude, Wiley painted young African-Americans in hip-hop costume. The painting hung quite convincingly alive in an Old Master frame.

In Los Angeles, I saw Robert Rauschenberg take on the full muscularity — even violence — of American continental discord, bald eagle, angora goat, hen and cock, toaster, rubber tire and all, in three-dimensional paintings he called “combines” to get past the critics.

Never underestimate what Roberta Smith recently called “the capacious subversiveness of painting.” As Libby Lumpkin warned in a lecture at the San Francisco Art Institute, “Desire takes place on the surface; there’s more to the surface than meets the eye.”

At the Philadelphia Museum’s Barnett Newman retrospective in 2002, curator Anne Tempkin followed the room of Newman’s Stations of the Cross with a room of contemporary paintings by artists who had been influenced by Newman’s work. There was in that room an Agnes Martin painting, an early Donald Judd and a Glen Ligon panel. The words in the Ligon were so painted into the white field that the painting seemed to resemble a tablet of the commandments, becoming even more of an object than Newman’s Stations. With the Ligon, one literally read the meaning of the painting. Seeing the Ligon in this context was a surprise and a revelation as to the continuing power of painting to include vast realms of experience.

A painter works in slow time, in physical space and with elemental physical materials: colored dirt and animal hairs at the end of a stick. It is a cloistered and individual practice. In this cloistered space, with physical materials, painters extend their traditions, converse with earlier painters, and search for new forms and new truths.

Painting is an anomaly, an ancient practice so wrapped up with human evolution, it seems to have come into being at the same time as human consciousness. Painting is still so wedded to nature that it might be the “canary in the coal mine.” If it dies, what does that mean for us?

*In the same issue, Joselit also has a review of SFMOMA’s Matthew Barney exhibition.