Feature: Reviews

Openings

- San Francisco Arts Commission Gallery

- San Francisco

- April 5 - May 18, 2002

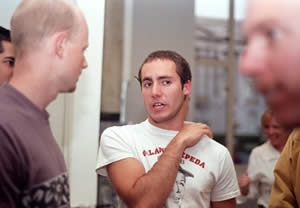

Openings, a series of exhibitions and performances at the SF Arts Commission Gallery, raised a host of conflicting sentiments about being a member of the art world. The self-referential exhibition called attention to gallery hopping as a social experience, where interaction between select individuals is at times paramount to the experience of viewing the art itself. Curator Natasha Garcia-Lomas conceived the theme after coming to the realization that the party atmosphere of opening receptions was the primary draw for visitors. A majority of the gallery goers would arrive on opening night to commingle and network, barely getting a glimpse of the work on view. Only a fraction of this number would stroll into the gallery during the daylight hours in order to actually observe the artwork. “Why not just take out the art on the walls and throw a series of parties instead?” she thought. Would that be enough to pack in a crowd? It apparently was. I attended two out of the seven openings and watched fast forward webcam recordings of the others on the website.

Overall, the turnout was impressive. Openings launched in the beginning of April with mostly bare walls and filled with work over the course of its seven mini openings, ending with a big closing party May 17. Some of the openings projects took the form of performances that involved gallery goers as participants. Jonathon Keats took count of everyone attending his opening, painstakingly documenting each visitor individually. He fingerprinted each person’s index finger with white ink on white paper, producing relics of the visitors’ presence and participation in a communal event, hanging them in a grid formation on the white wall. In their ghostly white on white countenance, the prints were a perfect embodiment of the transitory nature of performance as well as its ephemeral documentation.

Asha Schechter and Trevor Shimizu decided to interpret the networking game of gallery going literally, turning it into a highly competitive sport, complete with a scoreboard. They assigned a point value to certain actions generally witnessed at openings—a meeting between a curator and an artist; the sharing of information; and the exchange of business cards—and competed with one another to see who could score higher at the game. The race continued in a silent auction of signature plastic plates designed by a selection of their artist friends. Whoever could reel in the highest bids with their friends’ plate designs would win the game. When I last checked, Shimizu was in the lead by a few points, but I never did find out who finally came out ahead.

At first thought, both Keats’s and Schechter & Shimizu’s projects appeared to model themselves after the post-minimal, performance and action-based art of the 60s and 70s (Happenings, Fluxus, Actionists, et al) which gave primacy to the process of creation and to social experience rather than the finished, saleable art object. In this sense, their projects seemed to encapsulate the overarching theme of the Openings exhibition. But it should be taken into account that many of the Openings artists, in their twenties and thirties, belong to a generation that came of age in the 80s and 90s, in an era that witnessed the art market’s consumption of an earlier generation’s activist projects and socialist ideals (consider the high sale value that Joseph Beuys’s performance props commanded after his death). It was an era that promulgated the “art star,” a misconception that still prevails despite the market’s faltering financial stability. Either in reaction to the art world’s undeterred cult of the object and its subsequent creator, or in an effort to emulate and reinstate it, Keats and Schechter & Shimizu’s objects seemed to acquire an importance due to their attribution to a specific event or an individual, the fingerprints and signature plates spoofing the value accorded to art objects bearing the right stamp or signature.

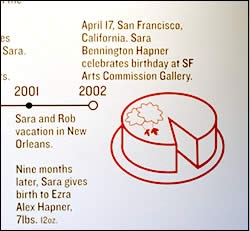

Possibly in reaction to the greed sparked by the rampant commercialism of the art world, some of the Openings artists opted to indulge in acts of generosity. Josh Greene held his opening on the date of his sister Sara’s birthday throwing her a surprise party. Cakes decorated with images of Sara during different stages of her life were sliced and eaten by gallery goers, some of them friends and family, others never having met Sara before. A timeline chronicling milestones in her life appeared on one wall, with markers such as: “While attending a luau, Sara’s hair begins to smoke, nearly catching on fire, 1983.” Although Greene’s opening was meant to come across as a gracious act for a loved one, it was dubious whether a Civic gallery was an appropriate venue for such a personal celebration. Could Greene have been referencing the intensely private nature of so much art that insists on plaguing the arts? Do audiences really want to hear the intimate details of other people’s lives, as profound as some artists might find their minutia to be? Greene was no doubt cognizant of his opening’s diametrical nature, straddling selflessness and self-indulgence in one go.

Liz Cohen’s opening was yet another extension of generosity, her aim being to equip careerists with the networking tools to get ahead in the arts. Cohen photographed about thirty movers and shakers in the Bay Area arts community, distributing the photos to gallery visitors with the subjects’ contact info listed on the back. The idea was to give artists and job seekers the opportunity to recognize these people so that they could pinpoint them at the next opening and make the ever-important self-introduction that might lead to a studio visit or an interview. It seemed like a naive notion to me. Dubious that it could yield the desired results, I contacted a high profile curator who had been photographed by Cohen and asked her for an informational meeting. To my shock, I received a prompt response and an invitation to meet, coming to the conclusion that sometimes it can’t hurt to drop the irony and undertake a more literal interpretation of the work. My only objection to Cohen’s project was its mode of installation. Ten prints of each of the subjects were hung on hooks for viewers to take. Over the course of the evening, it became a race to see who could get who’s photo before they all ran out, the portraits of those holding the most prominent positions being the highest in demand. It gave the project the air of a popularity contest, which regretfully diminished its overall sincerity.

Perhaps the weakest aspect of the Openings show was its insistent self-referentiality, reaching its peak in the work of Megan Archer and Libby Black. Archer painted portraits of “The Regulars,” a handful of folks who don’t work in the arts but who attend art openings regularly, and Black used photographs taken at Bay Area art openings as the source for her delicate drawings and cutouts. Using a reductive approach, Black highlighted a few figures in every scene, their gestures and outfits bespeaking the causal yet hip countenance commonly projected at receptions. Thanks to Black’s fine drafting skills, many of these personalities were easily recognizable—gallery owners, curators and artists getting drunk with their friends. Yet their familiarity further reinforced the stifling insularity of Bay Area arts circles. Both Archer’s and Black’s work seemed to solidify the direction Keats took with his installation, turning a lived experience into an artifact, something that could be titled, categorized, and commodified. It showed how self-referentiality poses an antithesis to the goals of actions-based artists—to reconnect art with everyday life. Whereas many of the artists staging events and performances in the 60s and 70s attempted to broaden the scope of their practice by pointing at something outside of the traditional sphere of the arts, the Fluxus artists even going as far as promoting what they called “living art” which they also termed “anti art,” Openings just pointed the finger right back at itself, thereby limiting its accessibility to those familiar with the art world’s rules of conduct.

Will Rogan and Bob Linder staged the last opening event, which took place the night before the show was to come down. They made the most of the evening by hosting a big party complete with a deejay. Button pins with imagery cut from the pages of a bird watcher’s field guide were distributed to visitors, so that everyone was walking around with wings, bills and beaks on their lapels. The pins could be seen as metaphors for the artists’ intentions. Once worn, they could collapse the walls of the gallery, dispersing their ideas and messages out into the larger world. Ideally, they would act as catalysts for communication, namely as a good conversation starter with those curious about the quizzical nature of their imagery. The simplicity and “open ended” nature of Rogan and Linder’s opening offered the truest interpretation of the show’s theme—art as a social experience that fosters communication. As such, it held the potential (but not necessarily the promise) of expanding art’s sphere of influence outside its own narrow community.