Feature: Reviews

Rene Yung: mountainriver

- Hosfelt Gallery

- San Francisco

- July 9 - August 17, 2002

Mountainriver: the physical features of one’s country, homeland.

As mountainriver began to take shape during the gallery installation, I realized I am leaving behind in this room a facsimile of my skin, shed and rebuilt in marks and words, air and seeds.– Rene Yung

When I first watched the film Iron and Silk, Mark Salzman’s story of his sojourn in Hunan province, China, teaching English and studying kung fu, I was struck by his evolution from a somewhat naive Westerner into a more philosophical and humble human being. This transition had to do with Salzman’s immersion in Chinese life, which for an American was filled with seeming dualities, illogic, and strong proprieties. He began to expand his worldview and perceive the relationships between his divergent cultural experiences.

Elements of this story come to mind when reflecting on Rene Yung’s installation mountainriver, which was on view at Hosfelt Gallery in San Francisco during the summer of 2002. The relationship between the film and the installation has to do with the ways in which Yung reflects on her experience of coming from China to live in this country. Her work becomes a meditation on what we leave behind and what we bring with us, how the diasporic experience becomes an interchange of original and exotic social and cultural experiences, and how we begin to talk about those experiences.

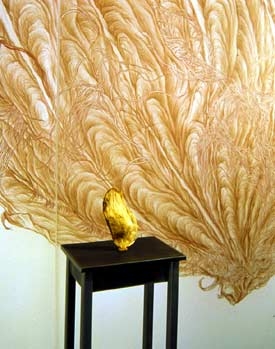

Yung uses deeply poetic means to make her transcultural experience palpable. Her explorations grew out of the activity of thinking about and collecting seeds, and the fortuitous circumstance of picking up a magnolia blossom – a seed pod of sorts – which she brought to her studio and began to draw.

As she became involved with this process, she began to play with scale in order to reference the European tradition of perception and explore its antithesis. While considering a nicoise olive pit and its remarkable topography, Yung realized it reminded her of quattrocento paintings of citadels with their crenellated city walls, as well as the topography of Chinese landscape painting. She found a way to express this affinity while subverting both painting traditions when she came across some Mylar, which she used as porous support for her seed pod and seed renderings. During a long and rich conversation we shared while drinking jasmine tea she’d brought back from Hong Kong, she explained her thinking, saying “seed pods, seeds ‚Äì we’re talking about the thing that carries within it the potential for self-renewal. It is nature’s carrier ‚Äì it is ‘ready to go’... a little package that is constantly being dislocated.”

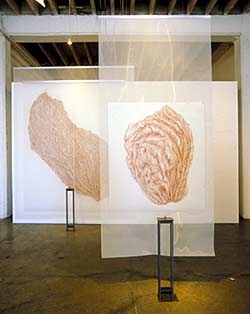

Of tremendous importance to the cultural experience Yung expresses in mountainriver is the hybridization of everyday visual language or, as she describes it, “a range or patois of vernacular.” This is reflected in her multiple visual and conceptual interweavings and juxtapositions of elements, centered around images of six fruit stones rendered 300 times their relative scale with graphite on translucent Mylar. The drawings are placed in direct juxtaposition with real fruit stone “models,” which represent the potential for dissemination and embody the unique topography she captures in her drawings. Suspended from the ceiling on wires, the oversized drawings float in undefined space, alluding to the unbounded space of traditional Chinese landscape painting and suggesting the liminal space between cultures.

The parallels between seeds and stones are amplified by the addition of Guaishi, often called “fantastic” stones or scholars’ stones. These strangely eroded rocks, prized for centuries in China as vehicles of contemplation, are valued for their cosmos-in-miniature qualities, the beauty of their form, texture, and color, and their suggestions of mountain-river landscapes. Yung carries the diasporic experience to yet another level of contemplation by juxtaposing a long wall of quotes and narrative fragments that express the experience of migratory dislocation with a “wall scroll” that includes six peepholes through which single, magnified seeds can be viewed.

What are the physical features of one’s country or homeland? As mountainriver illuminates, they are sensory and experiential, public and private. Their evocation here through marks and words, air and seeds, urges the viewer to imagine the dualities of leaving behind and recreating identity, translated through the act of shedding and rebuilding in marks and words, air and seeds.

mountainriver was one of a suite of four exhibitions at Hosfelt Gallery that explored relationships of contemporary art practice and theory with traditions of Chinese aesthetics and connoisseurship.