Feature: Reviews

Retrofuturist x 2

- New Langton Arts

- San Francisco

Editor’s note: Group shows are not always greater than the sum of their parts; bad neighbors can sap the strength of good works. But curators keep trying, because when they can pinpoint a clear hypothesis and the work to support it, it adds up to “Eureka!” The Retrofuturist exhibition at New Langton Arts this past spring was a provocative show with the highest ambitions. It was a natural pick for the continuing series in which we address the same exhibition from more than one point of view. Stretcher presents the Retrofuturist exhibition with both a review and a curatorial statement. - Meredith Tromble

Retrofuturist Curatorial Statement

by Berin Golonu

Why do we imagine the future? Some do it in order to visualize the possibility of creating a better present. Science fiction binds apocalypse and nostalgia together in the fantasy of a clean slate, a new start. It presents a range of possibilities that exercises and opens up the imagination. But sci-fi imaginings of the future ultimately speak of the present, and their fantastic scenarios can often be viewed as exaggerated metaphors for the social malaise of their authors’ contemporary day. The future cannot be imagined without a reference to the present or the past, which points to sensibilities, aesthetics, and social mores in dire need of change. In his seminal 1981 essay “Postmodernism and Consumer Society,” theorist Fredric Jameson describes how the cultural logic of late capitalism necessitates a postmodern present that freely blends the temporal sequence of the past and the future. According to Jameson, the postmodern condition is similar to the experience of a schizophrenic: “He or she does not have our experience of temporal continuity… but is condemned to live a perpetual present with which there is no conceivable future on the horizon.”

Having arrived at the future in the twenty-first century, it is no surprise that we are having problems trying to visualize what the next decade, let alone the next hundred years, hold in store. The twentieth century offered high hopes for the future. Stanley Kubrick envisioned the year 2001 as a time when NASA engineers would colonize the moon, teleconference with family members back on earth, and subsist on meals condensed to nutritional pills and lozenges. But the future doesn’t look as promising as it did fifty, or even twenty-five, years ago. Our faith in technological and scientific progress has soured in the aftermath of chemical disasters such as Chernobyl and Three Mile Island. Currently, the moral dilemmas posed by scientific breakthroughs such as the mapping of the human genome seem to outweigh the eminent health benefits promised by the bioengineering industry. This overpopulated, overdeveloped, postindustrial world we find ourselves inhabiting resembles the dystopias envisioned by George Orwell or Aldous Huxley more than the techno-utopias conjured by the visionaries of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Early notions of modernist art and design embraced the future with free abandon. There was a hope, exemplified by the Futurists of the early twentieth century, for instance, that technology and progress would uplift the spirit and free humankind from the tyranny of tradition. Many modernists, from the Cubists to the Constructivists, attempted to lend technological progress and scientific discovery a utopian aesthetic. “Atomic” design hit the mainstream in the fifties and the sixties, when streamlined cars were modeled after jet planes, when modern appliances and other consumer goods embodying a space-age look were advertised as functional, necessary gadgetry guaranteed to improve the quality of life for middle-class Americans.

Like a time machine reeling out of control, this futurist aesthetic has returned from the past to arrive in vogue again in the present. We see it resurfacing everywhere, from knockoffs of classic modernist furniture to kitschy advertisements for Altoids mints and Orbit gum. Even Hollywood has been churning out sci-fi classics from the mid-twentieth century with an updated look and a new cast of characters (Planet Earth, Lost in Space, Planet of the Apes, and rumors of a new Barbarella due for release in the next year or two). Why this return to the future? Are we suffering from imagination burnout? Or are we simply seeking inspiration from an era that had a brighter outlook on tomorrow? Perhaps taking a nostalgic look back reminds us of what our hopes for the future once held in store. Maybe the fetishistic aspects of futuristic design - perfectly embodied in the fashions and techno-gadgetry of early Bond flicks - hold a timeless appeal. Or maybe it’s just reassuring to know that the future envisioned by the past is not as fantastical as it might have seemed, that our apocalyptic imaginings for the future may be the latest expressions of a paranoia that has been with us since the dawn of modernity, and that life as we know it may not be all that different fifty years from now.

The artists in this exhibition look back in order to move forward. They reference the visionaries of the past in style and sensibility, updating their content to reference a contemporary mindset. They couple a tongue-in-cheek sense of humor with the methods used by twentieth-century sci-fi writers, illustrators, and filmmakers to illuminate their current societal ills and voice their apprehensions and expectations for the future. Some reference an exaggerated dystopia to raise consciousness and draw out a response, while others continue to envision unfamiliar, utopian environments (a metaphor, perhaps, for the realm of the imagination) in which to seek refuge from the immediate confines of our familiar world.

Retrofuturist Review: Back to the Future

by Terri Cohn

“And now here is my secret, a very simple secret: It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.”

“What is essential is invisible to the eye,” the little prince repeated, so that he would be sure to remember.

“It is the time you have wasted for your rose that makes your rose so important.”

“It is the time I have wasted for my rose—” said the little prince, so that he would be sure to remember.

“Men have forgotten this truth,” said the fox. “But you must not forget it. You become responsible, forever, for what you have tamed. You are responsible for your rose…”

“I am responsible for my rose,” the little prince repeated, so that he would be sure to remember.- Antoine de Saint-Exupery, The Little Prince, 1943

Turn-of-the-century periods are curious times; liminal spaces between the eras being left behind and the ones that have yet to unfold. In an art historical context, fin de siècle periods have been replete with revivals and revisions of stylistic trends, such as Neoclassicism at the turn of the nineteenth century, Post- and Neoimpressionism at the turn of the twentieth, and the Postmodernist and Neoconceptualist practices dominating the past decade or so.

Within this context, the exhibition Retrofuturist presented a curious perspective on the artistic zeitgeist of our current historical interval. The curatorial focus was on artists who are exploring the undiscovered past and future, via fantasy and science fiction, plastic and animation, as primary modes and mediums of expression. This seems a logical trend, considering the primacy of these genres and materials in global culture. Recent movies such as Spiderman, Men in Black II, and Attack of the Clones, and the movies based on Philip K. Dick’s 1960s science fiction classics, including the recently released film version of Minority Report, are pop culture indicators of the anxiety and nostalgia registering on this moment’s sociocultural barometer.

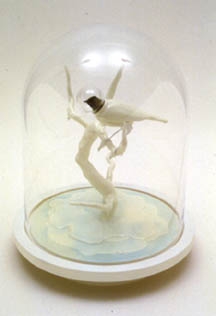

Following this pattern, the aesthetic of the artists included in Retrofuturist seemed nostalgic on many fronts, their work communicating a set of suppositions that was more humorous or fanciful than apocalyptic. From David Huffman’s Trauma Smiles paintings and ceramic sculptures of black superheroes, with which he confronts racial stereotyping, to Russell Nachman’s Power Converters Set gouaches of future/past land- and cityscapes, the exhibition reminded me how closely allied are our ideas of primeval and prospective worlds. This connection was underscored in Adam Ross’ odd architectural drawings; William Swanson’s Motel 6-like wall mural Growth Exhibit; and Luisa Kanzanas’ cast urethane diorama To Reach You, which suggested a 1950s hypothesis of a futuristic science museum display. By contrast, Leona Christie’s Ataraxy, a rather sweet, animated video narrative of a girl’s adventures in space, and Yargo Alexopoulos’ Far Moon, a dopey installation with video projection that felt like an early Star Trek set, seemed like wistful childhood recollections.

When I first saw Retrofuturist a few months ago, I questioned its prevailing aesthetic (plastic, juvenile), its entertainment value (one currency of recent art ), and its seeming lack of profundity. However, having seen a number of major shows in the intervening months - including the Eva Hesse and Yoko Ono retrospectives at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and Zero to Infinity: Arte Povera 1962-1972 at The Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles - I was reminded that art reflects the sensitivities and sensibilities of its makers in ways that are always about the concerns of its time. Further context seems provided by the uncertainties that emerged with the approach of the millennium and twenty-first century, and exploded in a sort of Armageddon in September 2001. Because there is still no way to explain or justify any of these events, these artists’ negotiation of hypothetical terrain provides at least a diversion from, and at best some hope for, a still cloudy future.