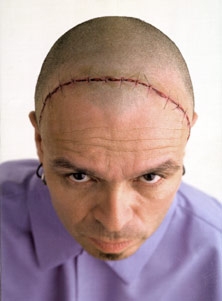

Self Portrait #3, Eighteenth attempt to clone mental disorder or How one philosophizes with a hammer, After J.G. Ballard, Crash/notes toward a mental breakdown (2002), Daniel Joseph Martinez

Feature: Reviews

Shock Treatment

- SF Camerawork

- Oct. 29 - Nov. 30, 2002

Without Anesthesia, or: This Isn’t A Nice Neighborhood

Recent Work by Daniel Joseph Martinez

One critical narrative of radical political art is that the artist must strive to shock the viewer out of complacency, even as contemporary media and popular cultures raise the bar ever higher - if not out of reach of the artist altogether - in rendering the violence of social relations into ghastly, aestheticized images fit for relatively safe consumption. Daniel J. Martinez long ago joined this battle, first making a name for himself in the so-called culture wars of the nineties (most famously with his “I can’t imagine ever wanting to be white” intervention at the 1993 Whitney Biennial). In his recent work, there is both continuity and rupture in relationship to his past aesthetic concerns. While the photographs that make up the bulk of Without Anesthesia certainly aim to shock and provoke, they also express profound ambivalence about the nature of such provocation (and the methods of its dissemination).

Some of the images Martinez presents: A bullet, fired from close range, exits a man’s head, his blood and brains spray outward. A severed tongue and ear. Eyelids stapled shut. Internal organs being pulled out from their torso. The artist considering his own decapitated head, served up cold on a silver platter. In this series of graphic conceptual photographs, gruesome close-ups of bodily violence are presented against mostly flat backgrounds, with the artist standing in as model or sacrificial victim. Clean, sharp colors make the aggressively violent nature of the subject matter vivid. And somehow, because these are, after all, photographs, it all seems too real, “more human than human,” to use the Nietzschean title that Martinez gives to the series.

But are these photographs, or “resemblances” of photographs? Perhaps it makes the most sense to think of the works as documentations of staged performances, themselves based on famous paintings, photographs, and films. They are palpably theatrical - “performances for the camera” - as well as implying narratives, and in that sense they take as much from the “No Movies” of Asco as they do the conceptual photography of Cindy Sherman or Artaud’s “theater of cruelty.” That each of the works at one level leans toward an art-historical or pop cultural reference certainly informs one’s reading (Martinez calls the titles that provide such references “footnotes”), but needn’t be the only frame through which to enter the work. These are, in a sense, “iconic” images, even if they come from photojournalism (Eddie Adams’ Murder of a Vietcong) or the movies (Cronenberg’s “Videodrome” and “Crash”); one can gloss the cultural and historical residue underpinning each image without recourse to the titles or an art history textbook. The larger point seems to be the interrogation of such residue as it collects in both reproduced images and our collective imagination.

There is the further issue of self-representation at play here, in two senses. Martinez “performs” upon himself, making these works as much about body art and self-portraiture as they are photography. Further, he inserts himself into predominately (white) Western images; Chicano identity thus takes on a fugitive presence, especially in the re-stagings of famous European paintings, where a photograph of Martinez’s severed head (even if we know it is “fake”) has much greater visual impact than Caravaggio’s equally gruesome Salome. Representation here becomes literal - re-presentation - as multiple layers of repetition and mediation (source image, its recreation, make-up and performance, photograph, etc.) reinforce the power of an image even as they deconstruct it.

The status of the image is at stake here, and while Martinez is certainly clear as to what side of the real/artificial divide he stands on (and for), he does well to avoid easy moralizing about technological illusionism. Indeed, his aim seems to be to recapture the power of art that Benjamin called the “aura,” using the very means of mechanical reproduction that were supposed to have killed off the magic of the aura in the first place. In an age of pure simulation and artifice, the “real” can only be grasped by artificial means - though, importantly for Martinez, by self-consciously critical works in which the layers of mediation and artifice become as much a part of the real as the experience of confronting his images can be.

One could talk about the simultaneous attraction to, and repulsion from, such images, of the discomfort in the face of such violent images, or how the logics of mechanical reproduction seem to transform the impact of reality into a series of aesthetic simulations. This is understandable, but such tropes have increasingly become mere platitudes, equally applicable to just about anything one encounters when turning on the TV or scanning the Internet. A more cynical artist than Martinez might settle for replicating ever-greater images of violence or, at the other extreme, retreating into tired discourses of simulacra and the seemingly dead-endgame of appropriation, irony, and mute affect. However, I think Martinez is trying to avoid either of these paths, even as the interpretive frameworks at hand would seem to want to pin him down within these well-worn aesthetic tendencies. Martinez wants to go beyond such art-critical truisms, even if by the route of putting them right back in one’s face. After all, to be able to explain, categorize and contain his work within such interpretive discourses is itself a kind of anesthesia, allowing the viewer to provide an additional layer of mediation between the work and its effects. At one level, then, Martinez is attempting to up the ante: “In order to heal a wound, sometimes you have to open it up to let the disease out. And sometimes you need to do that without anesthesia.” At another level, his works probe the processes by which such aesthetic “surgery” can be performed in a contemporary arena of anesthetized violence and commodified provocations.

Are these works - in the context of the gallery space - shocking, or do they more accurately register “shock”? Are there not works that sophisticated gallery viewers recognize as “shocking” or provocative not necessarily because they shock or provoke us, but because “we” presume they must certainly shock someone? Whose “bourgeois complacency” is being shocked here? Whose senses are being “reorganized”? Martinez seems to anticipate such queries, and his work’s almost clinical stylization might be a deliberate strategy to split the razor-edged difference between all-out in-your-face shock aesthetics and a deeper mediation on the position of the artist-provocateur in an age of over-saturated media violence and spectacle. Perhaps Martinez’s work here is as much about interrogating the aesthetics of shock value as it is about producing the more overt fireworks. Either way, one is left with a deep ambivalence about the artist’s ability to produce a recognizable shock effect, even one that transcends a familiar portfolio of violent imagery.

There is a lingering sense that the photographic works remain mute, trapped within their frames even as they wish to scream out “Be repulsed!” However, the lone sculptural work in the exhibition does manage to scream at the viewer, avoiding the clinical nature of the photos. I Pissed on the Man who Called Me a Dog, is an animatronic sculpture that bears an uncanny resemblance to Martinez himself. The doll-like figure stands in a small bathtub, periodically pulling out his prick and pissing on a mirror, while a soundtrack of shrill laughter explodes from beneath. The somewhat circular logic of the piece (male artist pisses on self-image, laughing all the while) is saved by the sheer creepiness of the animatronic doll, which is at once both clumsily mechanized (it is, after all, a doll) and oddly life-like. Whether the laughter is aimed at the viewer (“can you believe this?” “are you actually buying this?”) or at the artist himself, or both is unclear, but the effect is unsettling. The mechanized voice, repeating its peals with each fountain-piss, disrupts the staid gallery space with evidence of its own (self-conscious) bad taste. The bitter laughter thus becomes an almost uncontainable excess, a kind of fuck-you that attempts a “knight’s move” beyond the twin towers of complicity of cynicism. I hesitate to suggest that this piece proves that laughter is the best medicine, but instead read it as the artist-provocateur’s “revenge” against the conditions that might otherwise anesthetize his rage. And revenge, of course, is a dish best served cold - and without anesthesia.