Everything Must Go (Grey Market) (2006) by Stephanie Syjuco. Courtesy of the artist and James Harris Gallery, Seattle

Feature: Reviews

Tech Tools of the Trade - Contemporary New Media Art

- The de Saisset Museum

- Santa Clara University

- April 17 to June 28, 2009

In the expression “tools of the trade,” what’s the trade? The title of the deSaisset Museum’s current show, Tech Tools of the Trade: Contemporary New Media Art, suggests that the trade is contemporary art, and traffic in the new art places ever greater emphasis on the portability, durability, and ease of set-up and take-down of the works. “New media,” says the curatorial statement, here means “electronic, digital, or web-based,” and so is implicitly contrasted with what used to be called the multi-media basis of installation art. ‘New media’ then suggests issues of recognition, identity, and scale, as opposed to installation art’s typical concerns with participation, corporality, ritual, and residue. More fantastically, ‘trade’ also suggests trade-offs, and raises the issue of gains and losses in the artistic uses of these media. In his magisterial book The Engine of Visualization, the philosopher Patrick Maynard has suggested that in any kind of visual art there are trade-offs between, say, the degree to which the artist can offer the viewer a sense of detailed perceptual reality and the degree of guided imaginative exploration. When multi-media become new media, what’s the ratio between old and new?

Deborah Oropallo presents four works, each continuing her project of the last decade or so of suppressing the evidence of the brushstroke in painting while digitally recapturing and thematizing its past uses. The two larger works here from 2008, Head Nurse and Dark Tails, each show the head of a woman, dressed up and made over, offering her face for some blandly licentious fantasizing. One’s recognition of the faces is delayed and complicated by the application of the paint in long, discontinuous ‘strokes’, as if a two-inch digital ‘brush’, at once applying paint and scraping the surface, has been dragged vertically down the canvas. The works seem to comment, with a touch of helpless desperation, on the role of such images as the visual equivalent of an earworm, that banal tune that sticks in one’s head. Chagrined, we recognize these images and wishes that the complications of art could do more to cleanse the gates of perception.

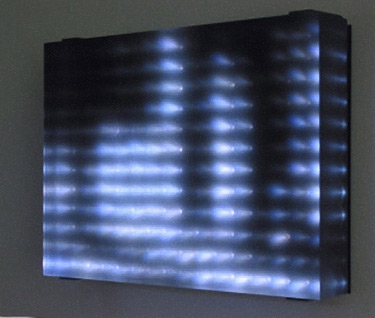

Another work, and a highlight of the entire exhibit, that conceives of new media as something developing recognition of contemporary life while re-figuring the old medium of painting, is Jim Campbell’s Reconstruction #7. Campbell presents an LED board with a grid of lights, 16 by 24, spaced at one-inch intervals. The lights dim and glow so as to depict an instantly recognizable but utterly placeless scene of urban traffic and pedestrians. With the simplest electronic means Campbell recreates the primitive magic of what Richard Wollheim called “seeing-in,” the human capacity to see a figure in a marked surface, while maintaining awareness of both figure and surface. Here the surface is light itself, whose primordial pulsing wondrously writes the prose of the modern world.

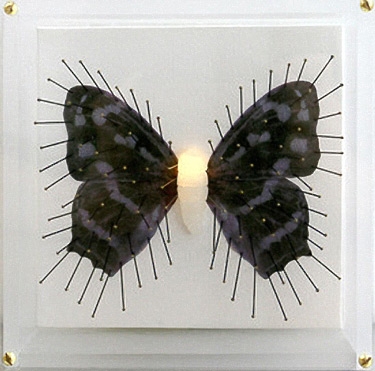

Gail Wight’s intriguing J’ai des Papillons Noirs Tous les Jours (an idiom expressing depression) uses a grid not to suppress and recall painting in new media, but to call forth the format of a natural history exhibit more typically submerged behind a piece of installation art.

Twenty-eight silk-winged butterflies are in individual cases, fifty pins per wing; their plastic bodies pulse seemingly randomly with light. It’s a work of great and melancholy charm, which first draws one in for close examination of the mutely colored wings, and then, as one retreats a step, fills one’s visual field with softly throbbing lights. This small scripted step is what remains of a typical installation’s typically more full bodied participation. Nina Katchadourian’s crowd-pleasing six monitor installation Accent Elimination also reduces the viewer’s movement to a minimum. The three outward facing monitors show individually Katchadourian and her parents— her father on the left speaking in heavily Armenian-accented English, her mother on the right with a lighter Swedish-speaking Finn’s accent. Katchadourian asks her parents scripted questions about their lives and languages, and herself speaks in accents ranging from unmarked American to ones close to her parents’. The three rear-facing monitors show the family meeting with a linguist who coaches them on changing their accents. The curatorial statement mischaracterizes this piece as having to do with how concepts of identity change in “our increasingly technologically oriented world,” whereas what one sees and enjoys is the playing out of an absurdist task, yet one tinged with existential depth, engagingly performed by the game parents and their earnest though slightly exasperated daughter.

There are a number of other works in the exhibit, though as is dismayingly common, several works were not being shown during either of two visits. Scott Kildall gives another version of new media’s affinity for an art of complicating recognition with five digital prints from his Paradise Ahead series. Each print depicts some canonical artist’s self-depiction of the past half century — Joseph Beuys and his coyote, Yves Klein and his leap — with an androgynous bleached blond(e) standing in for the artist; these works insinuate a programmatic claim of the relationship of new media art to earlier art that is more convincingly embodied in the other works discussed. The one “historical” work from 1983-4 is a piece by Lynn Hershman, who claims it as “the first interactive video art disc,” now shown on a television set from a DVD. Lorna offers the viewer the unappealing task of freeing the eponymous heroine by clicking a remote control, the implications of which are allegedly “immense and ultimately subversive.” The now century-long history of artistic avant-gardes is strewn with such illusions. The show as a whole rather suggests that the revolution will not be televised, it will be piece-meal.