Feature: Essays

Transgressions: The Art of Tag Team

In the summer of 1996, Walter Robinson and Tim Sharman were introduced by a mutual friend at an exhibition of Sharman’s paintings in a San Francisco gallery. When they met, Robinson—who has a Master’s degree in Sculpture from Lone Mountain College in San Francisco—was known in the Bay Area primarily for his cartoony, surreal wood sculptures. A “self-taught painter,” he had been “drawing secretly” for years in his journals and notebooks. He was attracted to the images in Sharman’s fluid, diverse paintings in part because they evoked the biomorphic forms and eccentric characters that appeared in his own notebook sketches, and he bought four pieces from the show.

As the two artists began to talk regularly on the phone, their discussions led them to initiate a series of collaborative mixed media drawings, which they sent back and forth to each other through the mail in a variation on the Surrealist’s writing game Cadaver Exquis. The ground rules for their experimental correspondence were simple and direct:

• Almost any material or medium was acceptable (Sharman jokes that they ruled out oil paint early in the collaboration because it was too messy and slow drying to send through the mail.)

• When a drawing left one person’s hands, he relinquished control over the image, and the other could make any alteration to it.

• It was understood that the drawings should be left "open" enough in each reworking to allow a subsequent contribution or addition, until it reached a point where both artists agreed the composition was completed.

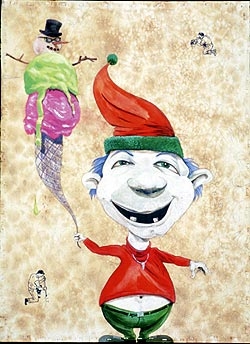

The constantly evolving pages that the two artists mailed back and forth across the San Francisco Bay were inhabited by “characters that came and went” as Sharman and Robinson embellished and altered each other’s successive contributions. Although initially they worked separately on the drawings, they spoke often to discuss what was “worth saving” while the pieces were in process. According to Sharman, “When one of us felt the drawing was going nowhere, it became a layer” adding to the complexity of the final composition. During their initial exchange of images through the mail, which continued for a year, Sharman would sometimes send Robinson as many as ten unfinished drawings at a time. Sharman has described their first series, executed mainly in acrylic, gouache and water-based media, as having a “light, airy, more layered feel” than the larger, denser, and sometimes dimensional pieces that were to come later. Robinson and Sharman produced their contributions to this first drawing series under highly informal circumstances, often working at home in the evening, in front of a television. Sharman, in particular, has described watching “B” monster movies or Pro-Wrestling tournaments while working on drawings, as if literally inviting subliminal content from “low” culture to seep into his mark making. As their work accumulated, the two artists named themselves Tag Team—professional wrestling terminology for a situation in which one member of a team tags his partner to bring him into the ring.

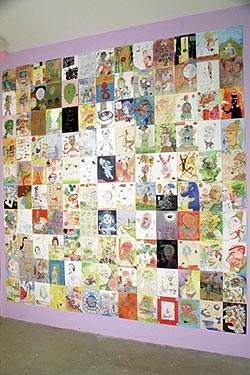

Tag Team’s initial collaboration resulted in a portfolio of more than two hundred 9” x 12” drawings that contained double portraits; appropriation from and stylistic mimicry of cartoons and advertising; an array of icons and themes gleaned from popular culture; sly satire; a strain of pointedly juvenile bad-boy humor marked by nostalgic references specific to baby boomers raised in the sixties and seventies; biomorphic hybrids; layering of almost archeological depth; fragmentation; sexual innuendo; extravagant mixtures of style and media; deliberate political incorrectness; a conscious blending of references from “high” and “low” cultural sources; and disjunctive, anarchic compositional and spatial devices—in short, the elements that have come to characterize Robinson and Sharman’s ongoing collaborative work.

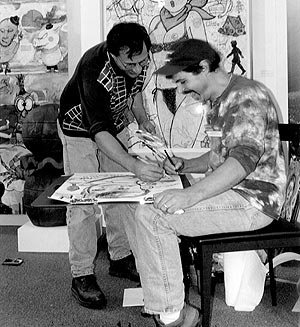

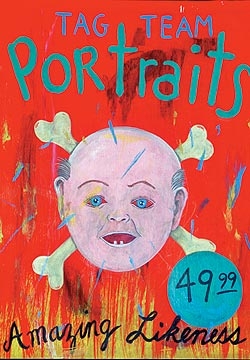

Tag Team’s first exhibit opened in November of 1997, at Catharine Clark Gallery in San Francisco. In the following year, Robinson and Sharman shifted from their correspondence-by-mail format to working on pieces together in the studio. At the first San Francisco Art Fair in September of 1998, and later that year for a benefit fundraiser at the Headlands Center for the Arts, they introduced a performance element to their process by drawing and painting portraits of contributing donors who had signed up for a sitting. Typically, during these performance-like drawing marathons, the two artists exchange tools and switch positions, crack jokes, and converse with onlookers while they alter and augment one another’s lines and marks on their shared compositions, revealing the energy and exchange the two experience working together in the studio.

The shift to working together was a natural outgrowth of having mutually defined a discrete area of subject matter and interests, and gradually developing a vocabulary to describe it. Their initial process of arriving at a completed composition through reacting to each other’s separate contributions has evolved into a more conscious implementation of styles and images that complement each other’s marks, or, conversely, jarring juxtapositions that humorously subvert them. Their ongoing dialogue, according to Robinson, remains rooted in their shared belief that “every resource has equal value—or can be equally insignificant,” whether adapted from the formal conventions of High Art in which both were academically trained, or appropriated from the lowbrow, vernacular sources to which both artists are attracted. Robinson has observed that from the beginning, their collaboration has been marked by a kind of mutual “generosity,” a desire to “set each other up” so that their works in progress could always accommodate additions or alterations. Their content, their technique and even their images they constantly morph from one form to another, the formlessness and elusiveness mirroring the idea that the collaborative process itself inherently breeds a kind of uncertainty as to final result. Process, rather than resolution, may be the point of the work—content giving rise to future content. The goal is not necessarily completion but rather evolution, discovery through reaction and response. Both artists describe their process as “play, a way to try anything,” an activity in which they give themselves and each other the freedom to be artistically spontaneous, without censure. Sharman has observed, tongue-in-cheek, that proprietary issues have never surfaced around individual elements that either artist has contributed to a composition because so much of what they use is already “stolen or appropriated.” (His 2005 exhibition at Nathan Larramendy Gallery is based on sculpted and spray-painted iterations of invented comic characters he calls “Doofs, ” which simultaneously appropriate and satirize Mission School grafitti styles.) Robinson concurs that disagreements and territorialism have never been a concern because “the rewards of our combined effort go so far beyond what I could so by myself.” In an art world where the standards of ego, style, and ownership generally prevail, Tag Team’s deliberate eradication of authorship is a rare anomaly.

That Robinson and Sharman share this degree of cooperation and trust appears even more unusual in the context of a society that carefully delimits social communication between men. Interestingly, many of their works on paper contain two characters, collaboratively developed by both artists, whose postures or gestures convey psychological or physical interaction, an implicit relationship. In some cases, one character was drawn first, and a second related character or environment was created in response. The “call and response” character of these compositions suggests an intuitive, non-linguistic communication between the artists, their friendship reflected in these accidental double portraits through the interactions of their rendered alter egos. With the hyperbolic, titillating content of many of their drawings—glimpses of pantied bottoms peeking out from miniskirts, women in push-up bras and g-strings, wet-dream depictions of girl wrestlers—Robinson and Sharman ironically underscored the limited range of topics through which two adult men born in the later half of the twentieth century are permitted to communicate intimately.

Influences

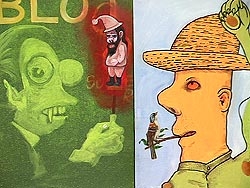

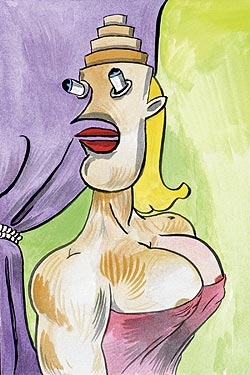

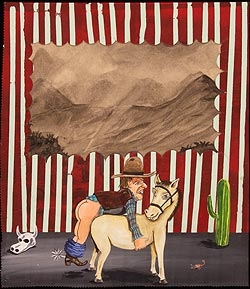

In describing the aesthetic that contributed to their first series, and to the larger works on paper, mixed media paintings and paper sculpture that they later developed, Sharman and Robinson have named sources as diverse as Big Daddy Roth’s “Rat Fink” cartoons, the art of Jim Nutt and the Chicago Imagist painters, Don Ed Hardy’s room-sized scrolls and the detailed, retro-style underground comic book ink drawings of R. Crumb and S. Clay Wilson. Both artists remember reading Mad Magazine, admiring the elaborately painted “funny cars” of the “dragster” culture, and copying “Rat Fink” cartoons in early adolescence. Many of their untitled mixed media drawings from 1998 and 1999 depict deliberately grotesque figures with malformed and exaggerated features—elongated, bloodshot eyeballs bulging from sockets, dangling tongues, crumpled postures—adapted from Big Daddy Roth’s characters. Sharman’s work in graduate school was shaped by the paintings of the Chicago artists who formed the Hairy Who; like those artists, Robinson and Sharman have professed their attraction to the “Bad” or “Naive” illustration style used in carnival and circus side-show banners depicting “freaks” and oddities. The Chicago Imagists, and Nutt in particular, share Tag Team’s love of vernacular sources and their general disregard for the conventions of “good” taste. Like the members of the Hairy Who, Sharman and Robinson are attracted to kitsch sources such as advertising illustrations, television and toys; like their mid-Western counterparts, Tag Team engages in visual/verbal punning, exploits surreal juxtapositions, and embellishes their figurative images with fragments of disjunctive text. One of Tag Team’s early untitled drawings—a muscular blonde standing before a drapery, her angular, robotic head contrasting with her buxom torso—utilizes elements of the flat, brightly colored graphic style and theatrical framing so intrinsic to the early work of the Hairy Who.

Robinson and Sharman have also declared their admiration for David Salle’s postmodern work, and have expressed affinity for the visual tropes used by Filipino painter Manual Ocampo. They were attracted to Salle’s reliance on layering and juxtaposition of unrelated images to create a narrative, and his free admixture of representational, quoted images and painterly elements with raw, sketchy marks. Robinson introduced Sharman to Manual Ocampo’s distressed, Colonial Baroque fusions of sacred and secular imagery through a catalogue of the artist’s work after the two had already begun to experiment with the kind of dark glazes and simulated weathering that characterize Ocampo’s painted surfaces. These abraded weathering effects are most apparent in Adios, Amigo, a painting depicting a man in a baseball cap flanked by the cultural icons Donald Duck and Batman, shown in Tag Team’s 1999 exhibit at Catharine Clark Gallery.

In their investigations of process, Sharman and Robinson have incorporated non-art collage materials like rub-on transfers, patterned wrapping paper, decorative stickers mass-marketed for children, and package labels. Random chance and the physical qualities of materials play a part in Tag Team’s creative approach, but both artists assert that the simple activity of working always supersedes their expectations about results, and that their completed work is simply evidence of the processes of problem-solving, reworking, brainstorming and improvising.

Their process/project-based approach led them from drawing and painting on paper to working in any and all materials that support collaboration and free improvisation: among the results have been hilariously uncanny detailed miniature sculptures of bicycles and vacuum cleaners, fabricated entirely from masking tape. For the 2003 group exhibition at Catharine Clark Gallery titled Sprout, Sharman and Robinson created a floor-to-ceiling installation of a giant flowering beanstalk made of hot glue and hand cut paper flowers, foliage and vines. (Sharman laughing cites high school parade floats and elementary school art class projects as the source for their architecturally imposing beanstalk.) They fabricated their most recent work, freestanding sculptural origami kimonos and cranes, from a textile-like 3 x 30-foot paper scroll that they had painted for nearly a year. As with the smaller drawings they’ve torn, cut, pasted and otherwise recycled, they used the illustrated scroll as raw material when they were dissatisfied with its qualities as a finished painting, opening a rich new area of exploration fusing appropriation and accident. “Accidental” process has played a part in their layered paint backgrounds made with poured or splashed pigment: a 1999 canvas, Cholera Sunset features a Pollock-like poured “sky” but is also framed and supported by a three-dimensional pair of crutches.

Their sly presentation of a “crippled” painting literally reframes Tag Team’s preoccupation with aesthetic qualifiers like “high/low”, and “good/bad”, issues they have continuously investigated in their work by presenting unworthy or degraded subjects with great facility and style, or by offering their audience historically or aesthetically significant content hobbled by self-consciously awkward execution. These presentation strategies further locate Tag Team’s paintings and drawings in the realm of transgression.

Of all the sources they quote in their work, among the most dominant are comics and cartoons. Sharman, a prolific and technically diverse painter with a Master’s degree from the California College of Arts & Crafts, has collected comics “since he was a little kid,” and as a consequence, is a skillful, fluent draftsman with a vast array of cartooning styles at his disposal. Tag Team’s constantly re-invented reality, as in cartoons, the rules of ordinary gravity, spatial relationships and scale don’t apply, permitting them to defy the compositional conventions of Western Art at will. Parts of Sharman and Robinson’s work incorporates the sexual exaggeration and racial, gender, and character stereotyping frequently found in cartoons—content that in their art, as in cartoons, discloses the sinister undercurrents and unspoken values of society in a stylized and seemingly innocuous guise. Culturally, in cartoons, we can enact violence and irrational acts without consequence; the ordinary rules of human suffering and degradation don’t apply to acts of physical, social and sexual mayhem committed in a fictively pictured universe.

The effects of comic or disastrous possibilities are simply erased or magically redrawn, as if pushing a reset button every time. Adapting a similar approach, each time Tag Team initiates a new image, they create a separate reality from the ground up—the empty canvas or blank page is always a speculative universe, a place of imagining what might happen , then executing it in the form that suits the moment of invention. Yet, Robinson and Sharman seem to be conscious of the mirroring capacities of the alternate reality they present, and that awareness has liberated them to explore hot button topics—sexual content, race issues, social behavior—often through hyperbole and distortion. To Sharman’s observation that “Comics parody what’s going on in the real world,” Robinson adds, “Everybody thinks these things but no one expresses them—it’s almost a relief to see them exposed to scrutiny.” They have frequently appropriated characters from the “Family Circus” cartoon strip to satirize family values and excessive sentiment, reframing the mother character as an object of sexual fantasy, or depicting the children in cross-dressed attire. Outside of their collaboration, both artists utilize satire in their individual work, and their partnership reinforces this anti-authoritarian stance. In Robinson’s estimation, throughout their collaboration they’ve tended to “depict problematic subject matter without any moral positioning, not offering a solution” so that interpretation becomes the responsibility of the viewer. In this sense most particularly, theirs is the essence of transgressive or subversive visual art; pushing out of bounds, it forces us to look beyond our ordinary assumptions about art and culture.

Editors note—We’re pleased to announce a new Tag Team artist multiple.

And don’t miss our Green room video interview with Tag Team.