Feature: Reviews

Venice Biennale

- Venice, Italy

- June 10 - November 4, 2001

Occasionally I have found myself in the fortunate position of being treated to a Sunday brunch buffet in a distinguished hotel. My initial reaction to such an invitation, of course, is to accept, then panic. It’s not that I don’t get enough to eat on a daily basis, but rather that the vastness of the offerings at this type of feeding is a true and rare luxury. Here, in a single locale, one can enjoy a comprehensive repast that spans two meals (breakfast and lunch,) and may include one or more of the following: exotic delicacies, carved meats, oysters on the half shell, delectable desserts, and savory and sweet libations. In order to take full advantage of such a spread, having a plan of attack is imperative.

Equipped with this knowledge, I relied on these strategies when I embarked on a five hour visit to the Venice Biennale, the contemporary art world equivalent of the grandest hotel buffet. In much the same way that the stomach can only contain so much food and drink, the human mind has limits to the amount of stimulus it can experience and process. At a massive art show such as the Venice Biennale, which has the ambitious goal of providing viewers with a sweeping international view of this moment, only so many works can register.

The notion of an artwork’s stickiness, its ability to adhere to one’s consciousness, becomes extremely prevalent in an exhibition featuring 63 participating countries and 130 artists. Harold Szeeman, Visual Arts Director of the Biennale, refers to the idea that there is something for everyone in this year’s exhibition The Plateau of Humankind. The show, he writes, "observes and gathers feelings, stories about social problems, ecological themes, the rhythms of daily life, the new technologies, work, sport, happiness and tragedy." The following is a brief sampling of Biennale works that have been lingering in my mind much in the same way that a thoughtful and delicious culinary effort does.

Lucinda Devlin’s (American) photographs (1999) are immediately inviting with their deadpan lighting and austere composition. Aesthetically, these images, a suite of 30 19 x 19 inch chromogenic prints, fit squarely within the visual vernacular of much of today’s photographs of interiors. It is not urban live/work spaces or suburban living rooms we are gazing at, however, it is a cross-country survey of American prison execution chambers. After viewing ten or so images, I began to only see color and line. The function of these spaces was momentarily negated as I found myself visually tracing the lines in the photographs and connecting them to the lines on the stone tiled floor beneath my feet. When I realized that I had managed to lose sight of the subject matter, the grave implications of these images and the questions they raise resounded with tremendous volume.

Taking his cue from Sol LeWitt, Bulgarian conceptualist Nedko Solakov left a set of instructions to be followed throughout the duration of the exhibition in A Life (Black & White) (1999-2000.) His directives follow: "A painter starts from the left hand side of a singled-out room, painting the walls black, clockwise. The first painter is to be followed, at some distance, by a second painter, painting the walls white, clockwise.’" Viewers were clearly confused by what appeared to be an installation in progress, but for those who took the time to read the explanatory wall text, this piece was a biting commentary. Unlike LeWitt, Solakov’s instructions do not result in a finished aesthetic product, but rather references the futility of both art and humankind.

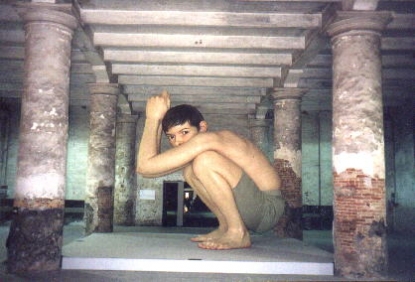

Ron Mueck, an Australian born artist, is almost guaranteed to make a lasting impression with both the location and the scale of his piece, Untitled (boy) (1999.) Mueck’s ‘Boy,’ a humongous realistic sculpture of a crouching pubescent child, is situated just inside the entrance of the Arsenale (one of the two primary spaces in the Biennale which houses works by over 50 artists.)

The placement of this piece is fitting as it reminds viewers of the sheer magnitude of the exhibition itself. In a gallery just beyond, Boy, Mueck showcases the depth of his model-making talents (he had a successful career as a model maker for film and advertising) in his piece, Untitled (Shaved Head) (1998.) This three-quarter sized model of a crouching naked man with a shaved head encased in a plexiglass vitrine, is so fastidiously rendered that I spent a good five minutes examining him to see if he was real. Minute details such as dry skin between toes and tiny thread like-veins add to the confusion. Though instantly captivated by the size of Boy, I found the intricate detail of Shaved Head to be more eerily impacting.

One thing is for certain: It is nearly impossible to leave a buffet or a biennale without feeling completely stuffed. But full – physically or intellectually – does not necessarily mean satisfied, and it is in this state that one must assess whether the number of tasty dishes measures up to the lofty expectations placed upon such an experience.

The Venice Biennale is on view from June 10-November 4, 2001. For more information Contact Visual Arts San Marco, 1364 Ca’ Giustinian 30124 Venice Italy; Phone+39 041 5218906, www.labiennale.org or e-mail: dae@labiennale.com