Feature: Reviews

Venice Biennale 2003

- 50th International Art Exhibition

- Venice, Italy

- June 15 - November 2, 2003

Imagine several thousand of the world’s leading (and not-so-leading) art world players spending several days trying to look and function at their best while actually doing just the opposite and you’ll have some sense of what the latest edition of the Venice Biennale was like. A thick, miserable heatwave lay over the city during the preview days and mostly dampened whatever little enthusiasm could be mustered for much of the exhibition and associated events (hot or not, large portions of the show were in fact quite uninspiring). Some pavilions bolstered their audiences with air conditioning while others were so hot inside that spending more than a few seconds within them was almost impossible. The Arsenale section of the show in particular suffered from this as the overload of works and the long, steamy walk through them blurred or erased most recollections. And the sheer number of artists with work on view (550, not counting the unofficial satellite shows) made a full reading of the exhibition impossible even if the weather had cooperated. Nonetheless, within this wooly morass there were a few notable features.

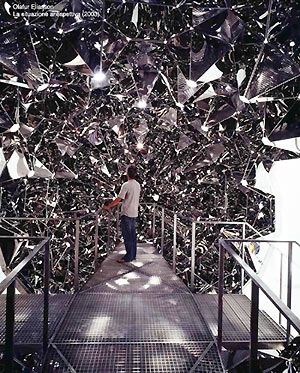

Olafur Eliasson’s makeover of the Danish Pavilion in the Giardini (no air conditioning but a nice breeze at the top veranda) into a series of radical transformations of visual perception was the only agreed-on hit of the show. It seemed odd that the official jury passed it over in giving the prize for best pavilion to Luxembourg’s Su-Mei Tse’s show in a small apartment across town (modest a/c, and the show itself is called air conditioning). The videos and installations on view here were not bad, but they did seem to be rather obvious meditations on time and sound: a video of street cleaners sweeping up piles of sand in a desert; a set of hourglasses that turn themselves over automatically when the sand runs out; a woman plays a classical cello suite at the edge of a ravine and is accompanied by her own echo; and, of course, one room stuffed with foam insulation to absorb any sound within it (I long ago lost count of the number of anechoic chambers I have seen presented as works of art). The likely curator of Luxembourg’s next Biennale entry told me he wouldn’t take the job if he had to use the same apartment for the show two years hence (Luxembourg holds a ten-year lease on it), but after the prize announcement this time around he may have to reconsider that demand.

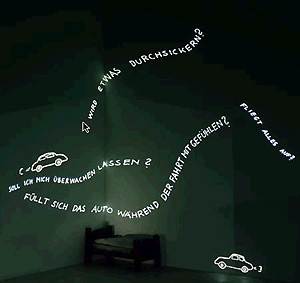

Also among the prizewinners, Fischli & Weiss’s slideshow installation in the Delays and Revolutions exhibit in the old Italian Pavilion (no a/c) was one of the few pieces to encourage a lengthy stay in a darkened room. Consisting of projections of simple drawings and short bits of curving text, the piece was both playful and contemplative, direct without being didactic. It set a standard that few other pieces on view matched.

In the Polish Pavilion (no a/c), Stanislaw Drozdz offered an illuminating challenge. He covered the walls floor to ceiling with dice, provided an elegant felt green table to roll six die yourself, and asked you to find the combination that turned up somewhere among the thousands of possibilities on the walls. If you find it you win, if not you lose. In an event that seemed premised all on winning and losing, the piece offered a wry commentary on everything that went on within it.

Fred Wilson’s entry at the US Pavilion (well implemented a/c), Speak of Me as I Am, showed his usual insight into revealing hidden histories, this time centered around the historical and contemporary presence of Africans in Venice. There did seem to be a curious split, though, in the presentation of work created specifically for the show and the inclusion of several pieces made a few years earlier.

Santiago Sierra bricked up the main entrance to the Spanish Pavilion (a/c unlikely) and permitted entry through the back only to those in possession of a valid Spanish passport (a pair of severe-looking guards ensured this remained the case). Reports back from suitably-equipped Spanish citizens indicated that there was nothing inside the Pavilion anyway, only the remains of the de-installation of the show two years ago. In an exhibition that aspires to dissolve borders and boost national pride at the same time, Sierra’s intervention illustrates a clear limit to those aspirations. The spare nature of the show also meant that Spain had a lot more money to spend on their party, which was fabulous.

The Arsenale (no hope of a/c) seemed a mishmash of various shows and agendas, all with unclear boundaries between them. Whether intentional or not, this was in part a result of a hasty job of wall labeling that provided little clarity. Hidden in the middle of the raucous “Zone of Urgency” section, a space which seemed at once both over- and under-designed, Chen Shaoxiong’s video of imaginary ways that skyscrapers could be designed to deflect airplanes brought smiles all around. Fewer smiles but no less interest surrounded Mircea Cantor’s deadpan video documentation of the manufacture of 20,000 double-headed matches in a Romanian match factory. These are pieces that seemed to ignore the curatorial conceits and stand on their own. There were a few, but just a few, other pieces here that worked equally well.

At the end of the long Arsenale trek, the over-inclusive chaos that made up Utopia Station (a/c no way) turned the last part of the Arsenale into a plywood art-shantytown and summer camp for adults. Including around 160 artists, the show featured lots of discussions, participatory projects, and free giveaways.

It is possible that some of the most interesting work in the whole Biennale might be found here, but under the heat and crowds and hand-lettered signs there wasn’t much chance of doing more than picking up a few manifestos or, in Yoko Ono’s work, stamping the words “Imagine Peace” onto various maps of the world. This latter gesture seemed more futile than ever both in reference to current political realities and to the chance that idealized art projects such as this could lead to meaningful change. In addition to imagining peace, the organizers could have imagined a functioning toilet somewhere near their Utopia, especially since there is a food station included in it (waste management is apparently not a high priority in this idealized community: the trash cans were filled to overflowing as well). A bit of welcome clarity was provided by Isa Gensken whose many guidelines about possible utopias included the succinct reminder that “projects involving nobody else than yourself are not utopic”. Perhaps more of these kind of insights will emerge as the Utopia Station project evolves over the course of the exhibition.

Perhaps as an antidote to all these hyperventilating experiments, Francesco Bomani’s retrospective of painting shown in the Venice Biennales since 1964 (Museo Correr, modest a/c) revealed the rewards of sharp curating and critical distance largely lacking elsewhere. While cherry-picking the best of four decades worth of work is bound to yield a good show no matter what, it is still impressive that of the 50 or so paintings on display here one is hard-pressed to find any that are less than first rate. In an oddly conservative way it brought a bit of hope that somewhere, under the heat, in the rest of the show there is work that would stick around and provide rich reading well into the future.