Feature: Reviews

Visit with Susan Felter

Post-Natural Ecology

Initially, it’s the petals that flag my eye. The magnolia opening to the light, its edges sharply etched against gray shadow, a green, veined leaf lofting in from the corner to contrast with the flower’s tone of virginal ivory. Yet on closer inspection, the reassuring loveliness of the image doesn’t quite hold. The petals are separating from their fibrous stem in a bow to inevitable decay. The magnolia seems to be under siege from a pair of giant ants invading its saucer leaves. Equally disorienting is the rapacious butterfly—a Magnificent Owl, or Caligo atreus—who would actually be bat-sized if the proportions proved true.

I have entered the “post-natural eco-system” of Susan Felter’s Hunting & Gathering series—a complex web of photographic images digitally arranged on exquisite prints whose “shameless beauty” (to continue the revelatory phrasing of art historian Andrea Pappas) is compounded by subtle ferocity, impossible acquaintance, and wave after wave of small disturbances negotiating between our perception of how flowers, birds, insects, and other animals should appear and how they have has been cunningly rendered.

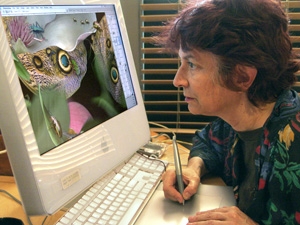

“I’m trying to entice and capture viewers,” Felter explained as I toured her studio—a new experience for me, though we have long been friends. “By offering something beautiful that draws them into a world that doesn’t quite exist. In my art life, I’ve always been attracted, for better or worse, to the edges where fantasy and reality meet. That’s where we experience the trepidation that’s necessary for impact.”

Felter’s work roves over a terrain of contradiction in which the peaceable kingdom has swallowed an omnivorous jungle. “I like the grace of living creatures, the sensuality of their textures and colors,” said Felter, “especially when combined with their potential and actual dangers.” Felter’s vision of nature—furthered by computer technology, rather than the uncertain slog of evolution—leads to unexpected, discomfiting encounters. The pixilated Magnificent Owl offers the unlikely opportunity to closely inspect his compound eye—a feat frustrated in the field by the organ’s minuteness and the butterfly’s instinctual flightiness. In Waxwings in Persimmon Tree, with its mad tumble of fruit, leaves, and feathers blurred together in frantic motion, the birds have contorted their wings in a manner that would make an ornithologist howl. In Western Stream, we’re confronted with the sheer improbability of stumbling upon a sand bed that includes a colonial era Mexican earring, I Ching coin, and gold chain—the embedded symbolic history of the West that also speaks to human conflict and ecological devastation.

Of course, Felter doesn’t take pictures of actual places. Instead, she fashions impossible images that appear authentic through a hybrid of photography, painting, computer technology, and—well, hunting and gathering. To assemble her subjects, both the living and the dead, Felter scrambles around beaches, forests, mountain streams, and most frequently, her own back yard in the East Oakland foothills. Vegetables, animal carcasses, the exoskeletons of insects, as well as lichen-laden rocks, dried grasses, and wilting flowers all wind up in her studio bins and kitchen freezer. “Animals in deep freeze,” she said, “it’s like having a bank account. I can always withdraw something interesting. But I’ve never killed anything to scan. I’m now much more sympathetic even to the ants who invade my kitchen. By collaborating on art work, I feel like we share a mutual world.”

Back from the field, Felter contemplates her array of flora, fauna, and minerals until something sprouts in her imagination. If an object manages to sustain her interest, she places it every-which-way upon her flatbed scanner, and then stores the results on her computer. Over the weeks, months, and now years—Felter launched the Hunting & Gathering series in 1996—she returns repeatedly to the collection in both digital and three-dimensional form, seeking linkages, experimenting with echoes and oppositions in shape, size, color, texture, and symbolic resonance. Then she begins altering and manipulating the images on the screen. In the course of a single work, she may patiently insert and layer up to one hundred Photoshopped images—a process that accounts for much of the series’ painterly depth.

Indeed, while Felter’s material source is photographic, the visual traditions she invokes historically belong to painting. One antecedent is seventeenth century Dutch vanitas paintings with their skulls, rotting fruit, smoke, and timepieces symbolizing the brevity of life. Felter complements the 400-year-old table arrangements of Willem van Aelst, Maria van Oosterwyck, and a host of lesser known moralizers to the lowland bourgeoisie with contemporary amalgamations of lizards devouring bugs, carnivorous flowers, and the corpse of a fish. Each design suggests its own demise and decay, hints of putrefaction amid loveliness—and insures our recoil even as we’re drawn closer. In the spirit of Dutch humanism shaking hands with a modern scientific world view, we’re also nudged to recall our own brief spell among the living.

The genesis for Hunting & Gathering grew out of the kind of happenstance that only blossoms upon a bedrock of hard work. Over the past three decades, Felter has pursued a distinguished career as a fine arts photographer, winning a Guggenheim for her series of cowboys and circuses in which she influentially applied the technique of combining her flash with an extended exposure to suggest movement within a dream-like spectacle. She has exhibited in individual shows in San Francisco, New York, and Paris, and her work is part of the collections at the Bibliotheque Nacional, Paris; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Houston Museum of Art; Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; and several private collections and museums in Japan.

In the mid-1980s, Felter began experimenting with photographic imagery on her computer. “I was into the crude messiness of video input,” she recalled. “I wasn’t looking for super-precision.” But with increased chip memory came improved resolution—and then, equally important, a serviceable flatbed scanner purchased by the art department at the University of Santa Clara, where Felter has taught photography for the past 24 years.

“For my fiftieth birthday party,” she recalled, “somebody gave me artificial flowers and I brought them to school, and set them on the scanner. I saw these extremely precise leaves and stems bathed in soft light, and I thought: ‘Oh, my god! It’s a seventeenth century Dutch still life.’ Not just the arrangement, but the quality of light with the flowers emerging from the darkness that’s produced when you leave the scanner lid open.”

Felter’s new tool mimicked the diffuse light of an overcast day in a world lit only by fire—or alternatively, a fluorescent bulb offering unexpectedly high contrast. The resulting image proved intensely three-dimensional—ideal for reshaping the contours of the natural world.

“People ask me why I use the scanner instead of a camera with lights I can control in my studio,” said Felter. “Part of it is the element of surprise. You don’t know how the scanned image will appear until you press the button. But mostly, it’s the magical light—high intensity with absolute depth.” Indeed, the lighting reinforces the improbability of what we’re seeing: the muzzy hues of an overcast day combined with intense background darkness; clarity at contrasting depths, with creatures who should be slipping out of focus nevertheless retaining their vivid detail.

While Felter’s work has been characterized as photo collage, she prefers the term “montage” with its intimations of film technique. “Collage suggests a physical cut-and-paste,” she explained, “leaving you with an object that’s one of a kind. Montage implies something more seamlessly smeared together, staged, rearranged, and reprinted.” Indeed, Felter’s studio is brimming over with the evidence of multiple takes on every print, with the arrangement of objects and background scenarios varying from the subtly distinct to the wildly opposed. One image dominated by a decrepit tree trunk flanked by birds scooping insects from the air exudes violence and panic with the depthless black background providing the free-fall integral to the power of her imagery. The same scene set against a clouded blue sky feels more playful, if imprecise—a wiggy Magritte with levitating log.

Felter received her graduate degree in filmmaking from the University of California, Los Angeles and she freely calls upon the field’s language and metaphors to characterize her current work. As we reviewed the overlapping images of Lizards and Mushrooms, Felter talked about how she “staged scenes” and “auditioned a bug” who failed to make the final cut. “When I placed some plastic flowers on the scanner,” she said, “they were suddenly elevated from ragamuffin to living elegance, like My Fair Lady.” As in filmmaking, Felter also acknowledges the value of teamwork. Indeed, the crucial casting call for Lizards and Mushrooms was conducted by Felter’s cat, Mokie, who dragged a flailing reptile in from the backyard so that the artist’s husband, Bill, could dangle him above the scanner as he froze stiff in terror. Like a skillful cinematographer, Felter then posed the ordinary lizard to turn him into a star art object, exploiting his distinctive visual qualities and adding new ones over subsequent pairings with leaves, grass, bugs, and—most disturbingly— fierce reiterations of himself.

“In the real world,” said Felter, “many of the creatures I portray would be at each other’s throats. In the art work, they’re caught in a swirl, a dance. Nature and culture have had a tumultuous 10,000 year love affair, and I feel a part of that uneasy thrill.”