Feature: Reviews

Touch - Relational Art from the 1990’s to Now

- Walter and McBean Galleries

- San Francisco Art Institute

- October 18 — December 14, 2002

Relational Aesthetics: Why It Makes So Much Sense

Back when hippies roamed the earth and vegetarianism was a cool new idea, art had to compete with social upheaval. Youths radicalized by the Korean and Vietnam Wars wanted to create new forms of connection with one another. The mass POP show in 1962, in which Andy Warhol was featured, is now widely accepted as the show that marked the end of modernism and was responsible for jump-starting postmodernism. There was a fundamental shift toward viewing the art process itself as a work of art; a healthy debate raged about how objectless art would be defined in the new era of postmodernism. In Europe, Joseph Beuys became a famous iconoclast by turning political fights into art. His exhibitions frequently included documentation of his environmental activism, and he often involved his students in his work. Beuys developed a fundamental message from his art practice: Everyone is an artist. But he wasn’t the only one making what he called “social sculpture,” social interventions as art. Remember the Be-Ins, the Love-Ins and the Happenings? Though associated with the hippie movement, these were really social phenomena that were interchangeable with the art practices of people like Beuys, Jim Dine, Yoko Ono, Daniel Spoerri, Alan Kaprow, Claes Oldenburg, and many others.

Nicolas Bourriaud’s TOUCH revives many issues of 1960s and 1970s art and addresses a new sense of connection between artists and their audience. Today people are being connected via e-mail, cell phones, satellite feeds, cheap video cameras, and even affordable air travel in ways that weren’t possible or convenient thirty years ago. In response, some artists now make work that is as much social interaction as it is art.

Fortunately for us, Bourriaud doesn’t throw a bunch of postmodern mumbo jumbo at us and expect us to eat it up like half-starved philosophy students. He avoids cumbersome explanations and instead offers us the work as it is. When you walk into the gallery, there is a display that allows you to pick what pages you want from the catalog and then you can bind them together yourself. This approach immediately puts the viewer in the position of creator, acknowledging Beuys’ message and setting the context for the show.

Bourriaud does two things with TOUCH. First, he curates a snapshot of the art of the 1990s and calls it “Relational Art.” Second, he illustrates different forms of social interaction as art that deal fundamentally with issues regarding public and private space.

Andrea Zittel’s Prototype for A to Z Pit Bed (1995/2002) resembles a kind of hot tub for meetings — just without the water. It is a silly wooden and carpet structure made for people to climb on and sit in. Although it is well built, to the uninitiated Pit Bed has no apparent function. Zittel gives us this wacky object and lets us make of it what we want. The furniture-as-meeting-place even has compartments to put things in, but provides no help in figuring out how they work.

Rirkrit Tiravanija, on the other hand, insists on interacting with “viewers” in order for his work to be made. For TOUCH, he worked with a youth group (part of the San Francisco Art Institute’s education program) to prepare a large meal in the school caf’s kitchen. This meal was shared by about thirty people. As they ate, conversations ensued, strangers met, and people walked around the room. Collecting such works means collecting the remnants of the experience, which are displayed in the gallery as Untitled (Tom-Ka Soup) (1995). This understated presentation (cups, cans, bottles, plates, knives, and forks that can be mistaken for trash) conveys an undeniable sense of fun. Unlike his historical antecedent, Daniel Spoerri, who transformed the residue from his meals by actually gluing everything down after his guest had finished and literally framing it, Tiravanija’s approach is casual. He considers the entire event, not the residue, the art.

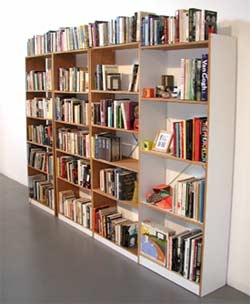

The bottom line is that this show is about relationships. Jorge Pardo’s Portrait of George Pocari (1995) is a set of large bookshelves with all of art collector Pocari’s books on it. In this clever deviation from traditional portraiture, we are invited to guess what George Pocari is like by reading the titles on the shelves. Pardo’s work is directly about connection and intimacy. Camille Paglia is placed next to Marcel Proust, and Andre Gide’s The Immoralist is next to Genet’s The Thief’s Journal. Do the arrangements mean anything? Why is a Woody Allen book on the top shelf while Shakespeare is on the bottom? This piece demands participation to be fulfilled, but it rewards you with a sense of who this person is or was. If I had to choose between a granite slab for my tombstone or a shelf of my own books, I might just go for the shelf. After all, what do people remember about you when you are gone? The more clues the better.

Similarly intimate is a heap of candy set in one corner of the gallery, called Untitled (Ross) (1997). This particuliar kind of candy was shared by Felix Gonzalez-Torres and his lover Ross when they were in Italy together. This is Gonzalez-Torres’ sweet memorial to his friend, who died.

Yet another strategy for interaction is to take art out onto the street. For her photo-based project Signs That Say What You Want Them to Say, Not Signs That Say What Other People Want You to Say (1992-93), Gillian Wearing asked passers-by to write down the first thing that came into their minds. The resulting photographs show the people with their handwritten thoughts. Often what they chose to write was entertaining, funny, or tragic. One tattooed man holds a sign saying “I have been certified as being mildly insane.” Despite his fierce appearance, there is a vulnerability that comes through as if he were telling us a secret. Another man, clean-cut, holds a sign that says simply “Queer and Happy.” Two punk-rock-looking teenagers (with bad handwriting) pose with a sign that says “Sex kills, die young and happy, ha, ha, ha.” Wearing makes the ultimate public art by turning the public into art.

Carsten Holler provides the most conceptual work in the show, Games to Be Played (1998). Holler devised five games. The catalog states that “to play these games, you do not need any materials (dice, playfield, etc.), just people.” They have titles like “games to be played alone,” “games to be played with others,” “games to be played with two people,” and so on. This is perhaps as reductive you can get as an artist — unlike Wearing, Holler doesn’t even give participants a sign to write on.

Although many of the artifacts are engaging as art, one is often left feeling like the party was over just as you got there. The sense that you almost made it encourages you to explore everyone’s leftovers — so in that sense it is a success. But to really get it, as they say — you had to be there.

Other artists in the exhibition include Angela Bulloch, Liam Gillick, Joseph Grigely, Jens Haaning, Christine Hill, Ben Kinmont, Laurent Moriceau, Philippe Parreno, and Gitte Villesen. Christine Hill and Rirkrit Tiravanija both did projects outside of the gallery environment.